A memento mori—Latin for “remember you will die”—is a practice, object, or artwork created to remind us that we will die, and that our death could come a at any moment. By evoking a visceral awareness of the brevity of our lives, it was meant to help us remember to make choices in line with our true values. The use of memento mori, which seems so counterintuitive today, is a practice that was found in cultures all around the world and for many millennia; it even lives on today.

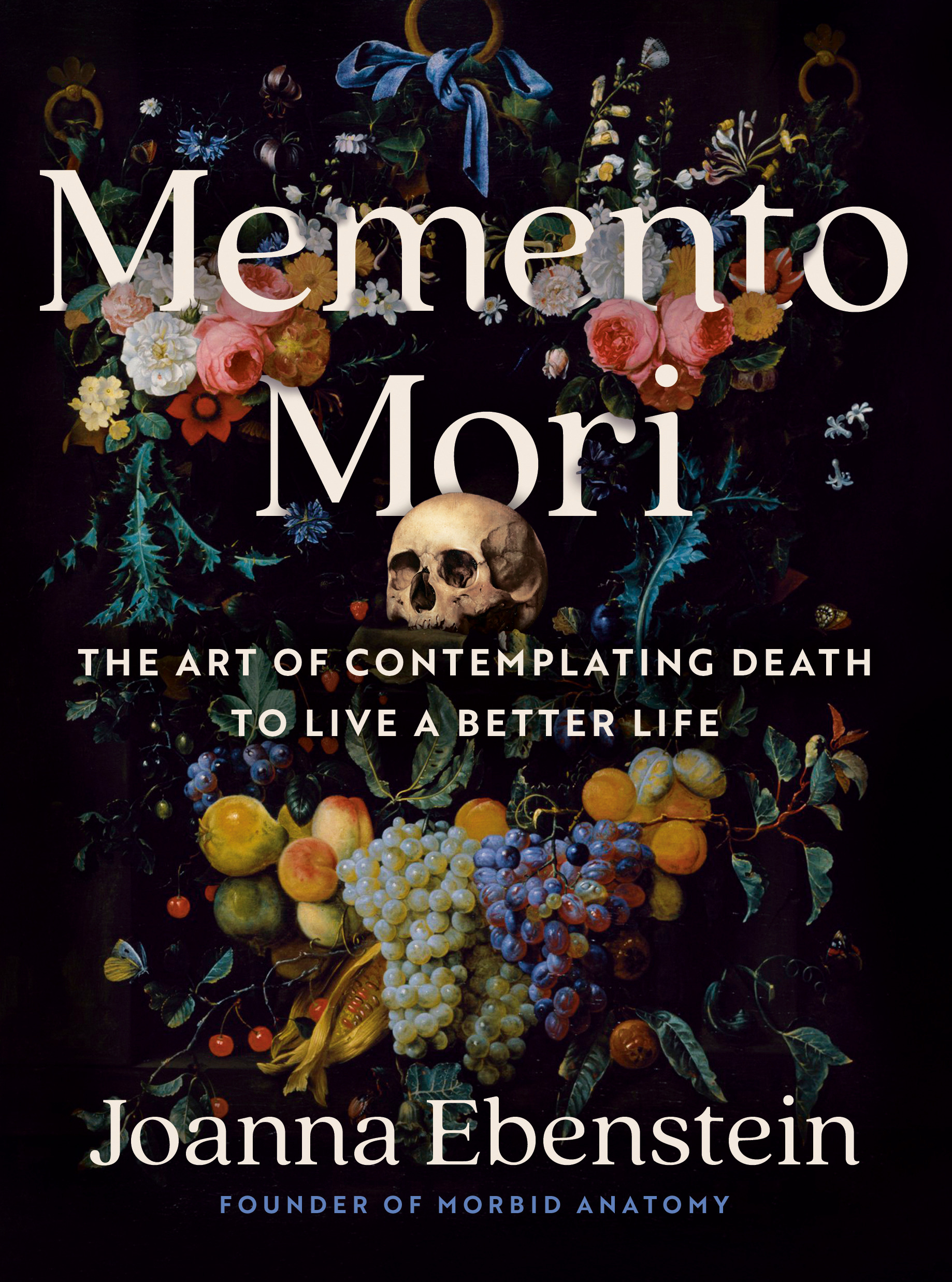

Memento Mori: Remember You Will Die

Talking about death has been deemed morbid, taboo, or even pathological. But in order to fully embrace life, scientists, psychologists, and spiritual leaders all agree—contemplating death is the key to living a life with meaning.

Memento mori were a part of life in ancient Egypt, where dried skeletons were sometimes paraded into a feast at its height to remind the revelers of the brevity of life. They were also frequently encountered in ancient Rome, where it was common to see skeleton mosaics on the floors of dining rooms and drinking halls. And, if you attended a feast, you might be gifted with a tiny bronze skeleton called a larva convivialis, or banquet ghost. In both cases, these memento mori were meant to ex- press the well-known Latin adage carpe diem—meaning “seize the day”—reminding viewers to eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow they might be gone.

Socrates, the ancient Greek founder of the Western philosophical tradition, asserted that a memento mori–like contemplation of death was at the core of the practice of philosophy. “The one aim of those who practice philosophy in the proper manner,” Plato records him as saying, “is to practice for dying and death.” Similarly, the Stoics, a philosophical school in ancient Greece and Rome, believed that one must contemplate one’s own death as a means toward living more fully and authentically. Seneca, a prominent Stoic philosopher, urged his readers to rehearse and prepare for death as a means of diminishing their fear.

Memento mori also play an important part in Buddhist practice. In the Buddha’s own time, there was a practice called the Nine Cemetery Contemplations, in which practitioners were encouraged to visit the charnel grounds—where bodies were left, aboveground, to be eaten by vultures or to decompose—in order to meditate on corpses in different states of decomposition. This was meant to help people overcome fear of death and release attachment to the body. This tradition even extends to artwork, in the Japanese tradition of kusözu, which are paintings that artfully depict these nine stages of a decaying corpse. Even today, it is not uncommon to find a human skeleton in places devoted to Buddhist meditation.

Skull in a case: memento mori, ca. 1650, Albert Jansz. Vinckenbrinck, at Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Christianity also makes use of the memento mori. In this tradition, it is meant to remind one to live a pious life, to resist earthly pleasures and temptations so that one will be ready to meet—and be judged by—God. Much as in the Buddhist tradition, Christians were, at one time, encouraged to meditate upon the dying and decomposing human body. Death was also, in the medieval era, brought to mind by the daily recitation of prayers called the Office of the Dead, which were supposed to prepare one’s soul for death and the Last Judgment. And, of course, every year on Ash Wednesday, devotees go to church, where the priest renders a cross in ash on their foreheads, a visceral reminder that from dust we are formed, and to dust we shall return.

In the Christian tradition, memento mori could also take the form of jewelry, including skull rings—often distributed as funeral souvenirs—and intricately carved rosary beads. Memento mori imagery was also commonly used in watches and clocks, playing on the close association between the ideas of time and death. Gravestone art regularly featured winged skulls or skulls and crossbones, and some grave markers—such as the lavishly carved tomb sculptures known as transi—even depicted the deceased in the form of a decaying cadaver.

Skeleton alarm clock (1840-1900), Science Museum, London / Science & Society Picture Library

There were also a number of fine art genres that brought memento mori imagery into everyday life. One of these was the vanitas (literally “vanity”) oil paintings, which featured imagery such as skulls and snuffed-out candles, symbolizing a life cut short. These were hung in the home to encourage the viewer to focus on the eternal, rather than the momentary pleasures of life on earth. Another popular genre was the triumph of death, in which an anthropomorphized figure of death plows down everything in its path, giving vision to the idea of death as an arbitrary and unstoppable destructive force. There is also the danse macabre, or “dance of death.” Popular at a time when the black plague was decimating Europe, these works also feature an anthropomorphized figure of death, this time merrily leading people of every age and social station—from queen to pauper to child—in a dance to the grave. This allegory points to the fact that death makes no distinctions; to death, we are all equal.

Memento mori could even take the form of actual human remains. To this end, wealthy gentlemen often displayed a human skull in their library or cabinet of curiosities as a poignant reminder of the brevity of life. And cemeteries—in a time before permanent interment— would dig up defleshed skeletons and exhibit the bones, frequently in artistic arrangements, to remind the visitor of their own death.

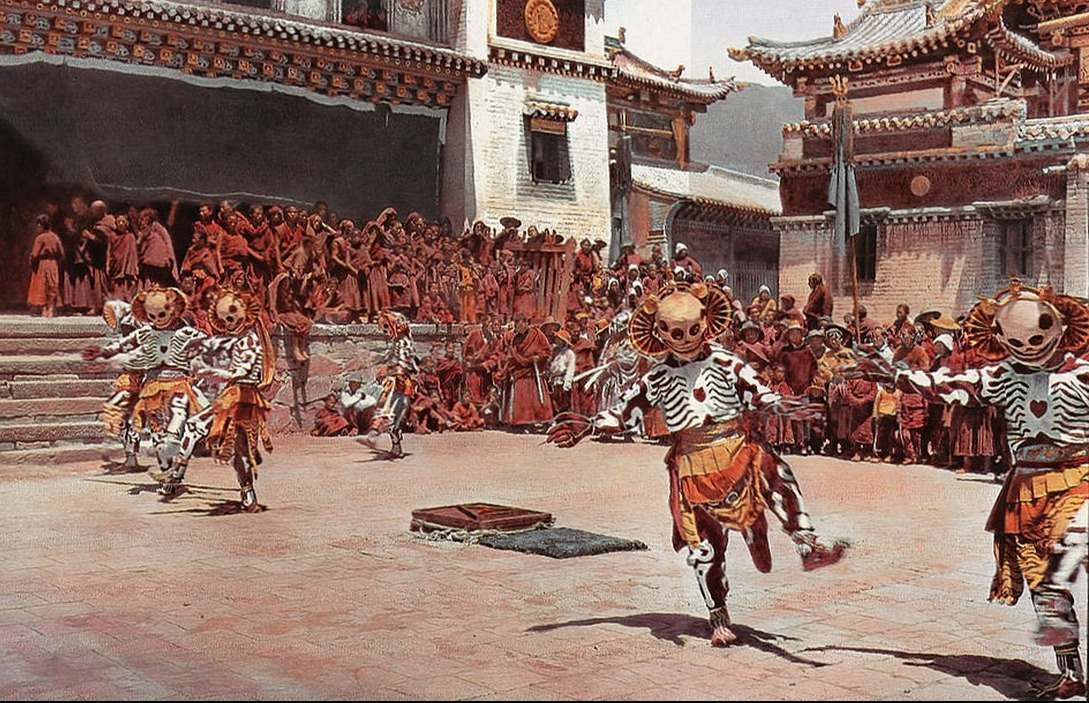

A contemporary manifestation of memento mori can be found to- day in New Orleans’s Mardi Gras, as part of the festivities of the Black Masking Indian krewe. Their annual procession begins at dawn when the so-called Skull and Bones Gang—dressed as skeletons—knock on the doors of neighborhood homes to remind them of the transience of life and invite them to join the festivities. In a similar vein, Tibetan Buddhist festivals often incorporate so-called cham dances. These are devotional performances that often feature costumed skeletons intended to remind revelers of the presence of death.

Tibetan skeleton dancers, 1925

A fun and surprising modern manifestation of memento mori is a smartphone app called WeCroak. The app—inspired by a Bhutanese proverb asserting that the key to happiness is contemplating death five times daily—sends you several thoughtful quotations related to mortality throughout the day. In the words of the app’s official text: “Contemplating mortality helps spur needed change, accept what we must, let go of things that don’t matter and honor things that do.”

Far from morbid, contemplating death in this way is the best method I’ve found for revealing, with clarity, what it is we really value. I have also found no better tool for inspiring us with the will and courage to make the changes necessary to live a life that is true to ourselves and in accord with our real values; one that will, or so we can hope, leave us with the fewest deathbed regrets.

From MEMENTO MORI: The Art of Contemplating Death to Live a Better Life by Joanna Ebenstein, published by Avery, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2024 by Joanna Ebenstein. MEMENTO MORI is available now, purchase online, or from your favorite local bookseller.

Joanna Ebenstein is the founder and creative director of Morbid Anatomy. An internationally recognized death expert, her books include Memento Mori: The Art of Contemplating Death to Live a Better Life, Anatomica: The Exquisite and Unsettling Art of Human Anatomy, Death: A Graveside Companion and The Anatomical Venus. She is also an award winning curator, photographer, and graphic designer, and teacher of the many times sold out class Memento Mori: Befriending Death with Art, History and the Imagination.