In 1887, it seemed as though one funeral procession passed by the Orton house each day. Inside, all seven Orton children had come down with diphtheria. The DuBrutz family in the next town over had already lost five of their children to the epidemic, believed to have been caused by miasma – the terrible stench that emanated from the thousands of dead cattle and sheep covering the plains after the rains came that year. The pioneer families of Central California were dying so fast people resorted to taking apart their barns to provide wood to build coffins for their loved ones.

Windows were boarded up and people shut themselves away within their homes for fear of contracting ‘the plague.’ Neighbors dared not help one another, fearing contact with others would cost them their lives, leaving people isolated and alone in their grief to carry out the tasks of preparing and caring for their dead.

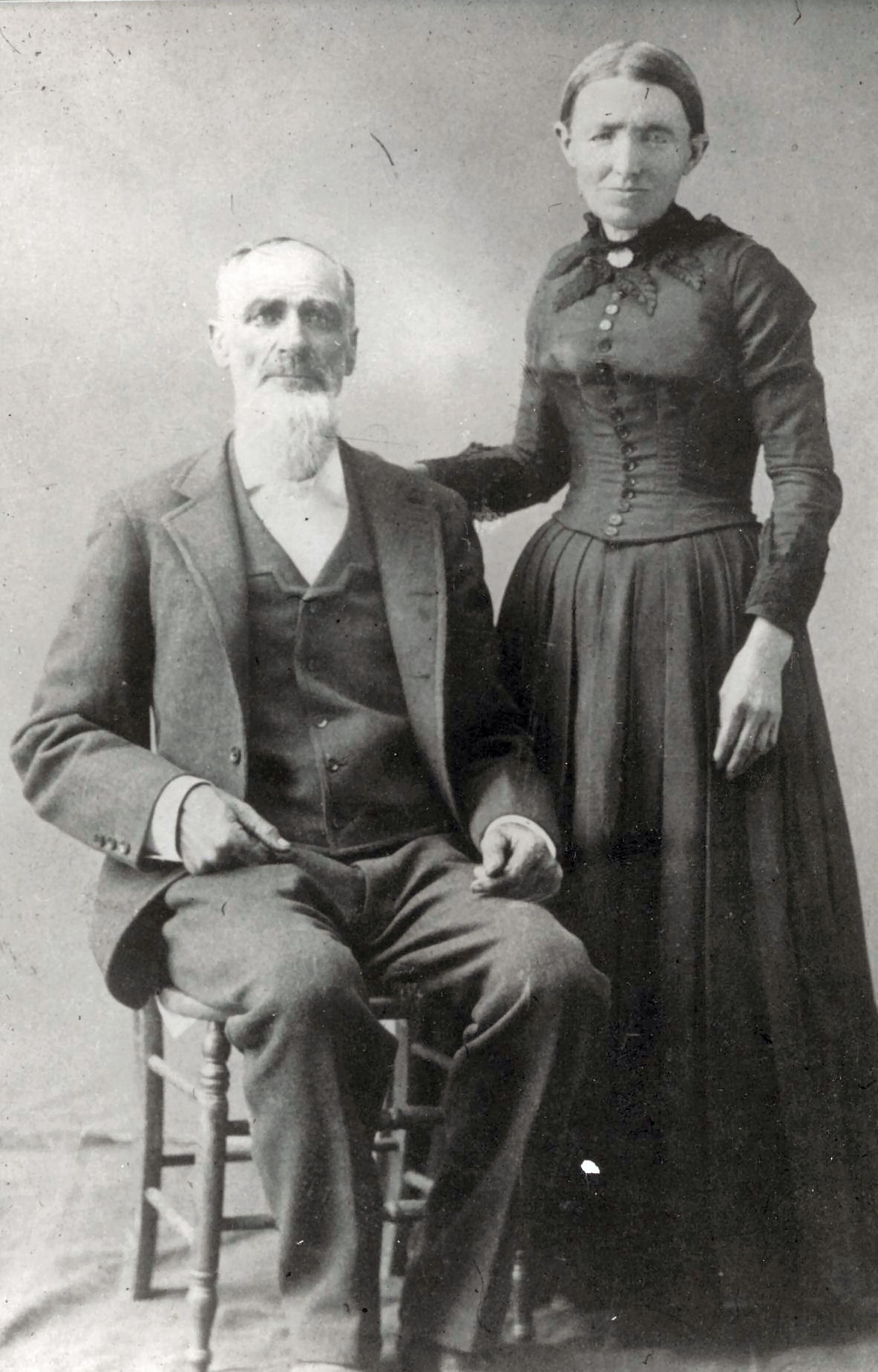

Only one woman in the county dared to enter their homes to lay out and bury the children when they died – Katherine Burns. Armed with a medicine that was “so powerful it would eat holes in clothes on which it dropped” (Ina Stiner, Early Family Histories), a washing tub to bathe in, and an extra set of clean clothing for herself, Burns took on the death work no one else would.

I first uncovered the story of Katherine Burns when I was hired on to be the curator of a small, Central California farming town’s first historical museum. Then I was asked to write the first book dedicated to their local history. I didn’t expect to find much beyond infighting among farmers and maybe some interesting agricultural innovations. I certainly didn’t expect to find much in terms of women’s contributions.

I was wrong.

The contributions of women in the community were ample, and impressively death oriented.

In the newly forming town of Lindsay, the small population of just a few hundred was rapidly diminishing during the epidemic. A local farmer offered to donate land to create the first communal cemetery in the area, however, no one volunteered to claim the deed, and with it the responsibility for the town’s deceased. In the end, it was a 20-year-old woman, Miss Kincaid, who took possession of the land and established the first cemetery. She did the grounds keeping, record keeping and even dug the graves.

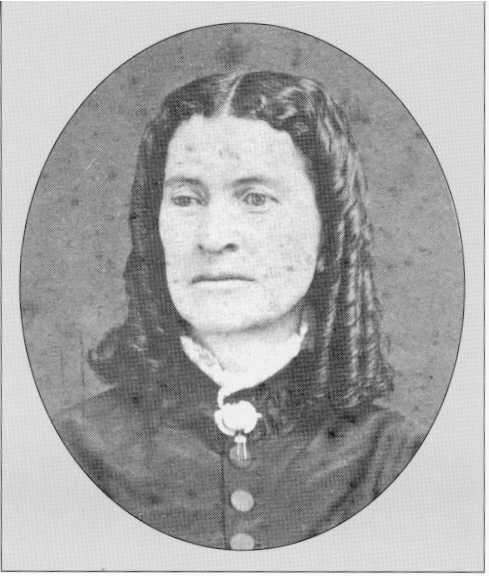

In the 1930s Lindsay’s Orange Blossom Queen, Charlotte Bequette, was the daughter of a wealthy rancher and considered “the Belle of Lindsay.” What they didn’t know was that her grandmother was once known as “the Belle of the Donner Party.” She was Mary Graves, a surviving member of the ill-fated Donner Party – you know, the pioneers that got snowbound and tuned to cannibalism? Yes, that Donner party.

Shortly after Graves’ rescue she married Edward Gant Pyle and they moved to San Jose, California where she became the first female teacher there. However, their joy was short-lived when Pyle went out one day and never returned home. His body was found, almost a year later – he had been murdered. Pyle’s killer was captured and imprisoned. While the murderer awaited execution, Graves stayed at the jail, tended his wounds, cooked his food and kept watch over him – all of this to ensure he survived long enough for her to watch him hang.

Discovering these stories of women largely forgotten by the communities they served, engaging in various aspects of death work or confronting their mortality in my own backyard prompted me to wonder how many other stories there were? So, for the past two years I have been uncovering extraordinary stories of women who have done the same:

The first female undertaker in the U.S. who was active in the Underground Railroad.

The Empress Consort who had her corpse laid out to decompose on a busy street to teach others the value of contemplating one’s own mortality.

The librarian who spent her lifetime identifying thousands of immigrants who perished as a result of a natural disaster, while exposing the men trying to hide those deaths to make a profit.

Over the next several months, I look forward to sharing their stories, alongside many others, in a new series here at The Order – Great Women in Death History.

Sarah Chavez is the executive director of The Order of the Good Death and co-founder of Death & the Maiden, a project that endeavors to explore the historical and cultural roles women have played in relation to death. She also has a blog, Nourishing Death, which examines the relationship between food and death in rituals, culture, religion and society. You can follow her on Twitter .