Learn more about the events that shaped the Death Positive Movement.

History of the Death Positive Movement

Timeline of the Movement

1970s – 1980s

Movements rarely exist in a vacuum. They build on the work of previous activists, movements, as well as historical, political and social events. The Death Positive Movement is no exception. The 1970s and 1980s created the foundation for the Movement as we know it today.

1974

Hospice Movement

Inspired by the movement in the UK, the first hospice in the U.S. opened in 1974. In 1978 the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare determined that “the hospice movement as a concept for the care of the terminally ill and their families is a viable concept and one which holds out a means of providing more humane care for Americans dying of terminal illness while possibly reducing costs. As such, it is the proper subject of federal support.” Today, experts agree that the Death Positive Movement has fueled hospice growth.

1976

Natural Death Movement and the Natural Death Act

This legislation gave individuals the right to refuse unwanted medical intervention to sustain life. Living wills and Advanced Directives were a direct result of this act which passed in the U.S. in 1976. Today, Advanced Directives are a powerful tool for trans and nonbinary people to protect their identities in death.

Dia de Muertos in the U.S.

In the 1970s, civil rights issues surrounding education, farm workers rights, police brutality, and war gave birth to the Chicano Movement. In an act of resistance to U.S. society demanding that Chicanos assimilate, people began embracing their roots in defiance. As a result, the imagery and rituals of Dia de Muertos were moved from the home into the public sphere via protests, events, art shows, and performance art, confronting Americans with death and the demands of the movement. Decades later in the burgeoning Death Positive Movement, Dia de Muertos imagery and rituals have been widely referenced to advance discussion around death.

To learn more, check out Day of the Dead in the USA: The Migration and Transformation of a Cultural Phenomenon by Regina M. Marchi

1980s

Death Acceptance Movement

Palliative care was introduced more widely in the U.S. during the 1980s. It offered an interdisciplinary approach to care for individuals with a life-limiting illness, with the goal of enhancing a patient’s quality of life. Part of the palliative care discussion surrounded the care of terminally ill patients and those in hospice care, and was focused on ways to help those patients and their families come to terms with their inevitable end of life. By doing so, death acceptance advocates argued that the focus could then shift from denial to enhanced care and quality of life instead of unnecessary and costly medical interventions that may prolong life but would likely prolong suffering.

To learn more, take a look at Death, Mourning, and Medical Progress by Daniel Callahan

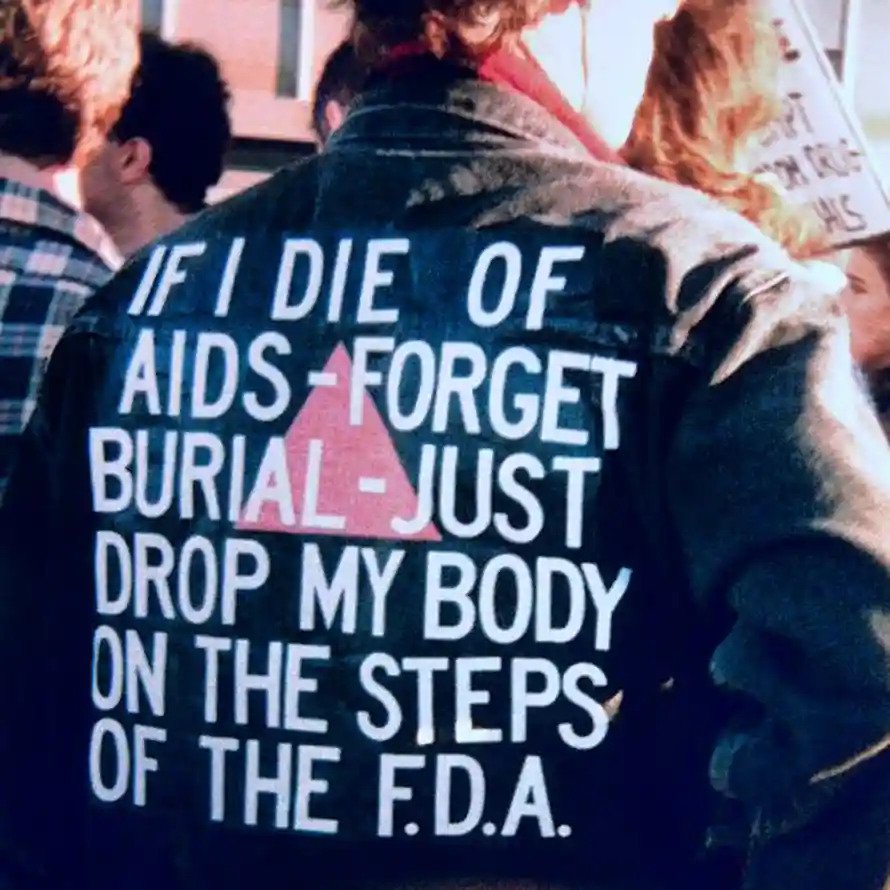

AIDS Activism

A lack of understanding about HIV/AIDS, demonization of victims, and the willful negligence of the U.S. government gave rise to the myth that those dying from AIDS and their corpses were a public health and safety hazard.

AIDS activists demanded, among many things, acknowledgement, and scientific research through protest tactics like ‘die-ins’ which “forced social and cultural institutions to take responsibility for AIDS deaths by having to physically move the protestors’ bodies.” Meanwhile, community death care providers worked tirelessly to restore dignity and humanity to AIDS victims while many hospital staff, embalmers, and cemetery personnel would outright refuse to provide services and care for AIDS victims in death. In result, community death carers took on the necessary care–from shepherding patients though the dying process, to preparing their bodies for burial, to ensuring that they were given a proper internment they deserved.

Books

Landmark books that helped form the foundation of death work and expand our understanding of mortality.

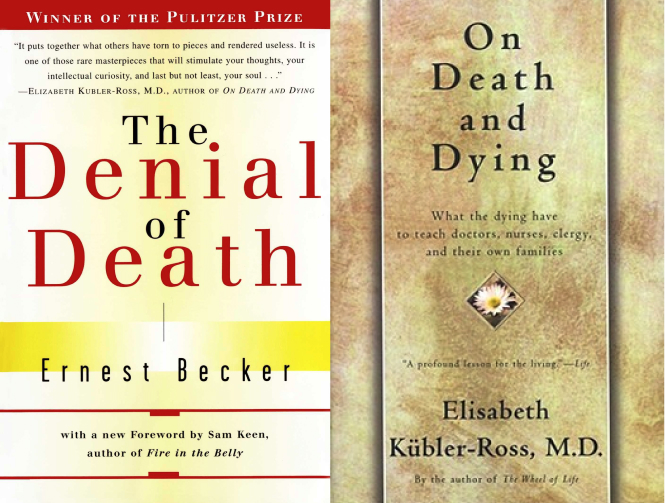

The Denial Of Death by Ernest Becker (1973)

This Pulitzer Prize winning book argues human behavior is motivated by our fear of death. Becker’s work would hugely impact the tenets of the modern Death Positive Movement.

On Death and Dying by Elisabeth Kubler-Ross (1969)

Kubler-Ross’s bestselling book featured interviews with dying patients, helping the public to understand how death affects patients, medical professionals, and their families. Though her famous five stages of grief have fallen out of favor as a model, her impact continues.

1990s

The 1990s saw the emergence of green burials and home funerals.

Green Burial Movement

What we call green or natural burial–a simple hole dug in the earth and a body placed within—the very definition of a body returning to the earth—has always existed and been practiced. However, in many areas of the world cemeteries require that bodies be put in a casket before being placed in a concrete or metal vault. With an increasing consciousness and concern about climate change and the impact our actions have on the planet, green burial advocates voiced the need to scrutinize the effect “traditional burials” were having on our environment. The first conservation cemetery in the U.S. opened in 1998, influenced by a similar movement in the UK. The number of dedicated green burial spaces grew exponentially in the 2010s.

Learn more about Green Burials.

Home Funeral Movement

Home funerals, or what used to simply be “a funeral” prior to the establishment of the funeral industrial complex, were once the norm. In the 1990s various individuals around the U.S. began to independently advocate for family conceived and led death care. Many are now interested in educating and supporting others about their right to be involved in the care and keep a body at home, as well as create more meaningful end of life experiences. As a result, a powerful movement surrounding the protection and exercising of these rights has emerged.

Learn more about the Home Funeral Movement.

2011

Around 2011 several new death related initiatives emerged. Synchronously, previously established efforts gained public support and traction. Together, they would help form the building blocks of the current Death Positive Movement.

2011

Death Café

The Death Café model was developed by Jon Underwood in London in 2011. Underwood described the social franchise as an event where “people, often strangers, gather to eat cake, drink tea and discuss death. Our objective is to increase awareness of death with a view to helping people make the most of their (finite) lives.” This model, which allows anyone with an interest to act as host and facilitate the gatherings in casual, public environments allowed Death Cafes to flourish in 78 countries around the world. During the Covid-19 pandemic Death Cafes moved online and experienced an additional surge in interest by providing a virtual space for people to discuss and process the death and grief they were experiencing.

Learn more about Death Café.

Natural Organic Reduction (Human Composting)

In 2011 Founding Order Member Katrina Spade was in the Master Of Architecture Program at the University of Massachusetts Amherst when she began thinking about the environmental impact of traditional burial and cremation, prompting her to ask “How could you bring nature to urban death care?” After a decade of work and innovation Spade’s work has become a viable option with natural organic reduction being legalized in Washington state in 2020, and the first facility opening to the public. In 2021 NOR has become a legal option for people wanting more sustainable death care in Colorado and Oregon, with legislation in several more states in process.

Learn more at recompose.life.

Death Doulas

An off-shoot of the Home Funeral Movement saw the popularization of the role of Death Doulas or Death Midwives, an ancient practice which provides nonmedical support and guidance to dying individuals and their connected circle of family and community. Many Death Doulas are also home funeral advocates who guide families who wish to care for a body at home and support in the creation of authentic, family led funerary rituals. The recent interest in Death Doulas has helped to establish the understanding that a good death is a part of a good life.

Learn more about Death Doulas.

2011

The Order of the Good Death

In 2011 Caitlin Doughty, a young funeral director, was able to witness firsthand how the funeral industry set families up for failure both financially and emotionally. Recognizing that the problems were entrenched, Doughty founded The Order of the Good Death to reframe what was possible at the end of life, gathering together a community of funeral industry professionals, academics, and artists who were at the forefront of changing these perceptions. She also began Ask a Mortician, a web series on death questions and issues of death positivity that has been viewed almost 200 million times. This community grew and expanded into the Death Positive Movement, a term that began here at the Order. In the years since, death positive has become an international Movement that includes everyone from high level practitioners to members of the public.

Read an article about the Death Positive Movement on globalwellnesssummit.com.

2012–2015

The following events helped propel the movement forward and define what it would become.

Morbid Anatomy Library and Museum

Morbid Anatomy got its start as a personal blog and later evolved into a brick and mortar community space and museum in Brooklyn, NY which captured the zeitgeist of the Death Positive Movement. Created by Founding Order Member Joanna Ebenstein, and others, Morbid Anatomy hosts a wide array of events dedicated to “exploring the intersections of death and beauty and that which falls between the cracks,” including exhibits, lectures, workshops, film screenings, tours and more. They continue to offer a robust schedule of diverse events.

You can learn more about Morbid Anatomy on morbidanatomy.org and by watching this video.

Zen Hospice

A leader in the hospice movement for decades, Zen Hospice’s human centered model of end of life care took the spotlight thanks to hospice and palliative medicine physician BJ Miller’s popular 2015 Ted Talk, What Really Matters at the End Of Life? and Oscar nominated documentary End Game.

Black Lives Matter co-founder Alicia Garza’s mother was one of the last patients at Zen hospice prior to their closing in 2018. About the experience she said, “For our family, hospice became about embracing death. Embracing the life that we have left with as much agency and dignity as possible… What it meant for my Mom to die with dignity, our experience of care and caregiving, was essential and it is not the experience that so many families have across this nation.”

Visit the Zen Hospice website.

TED Talks

At the beginning of this decade, the popularity of TED Talks exposed a wide audience to the work of contributors to the Death Positive Movement and pushed conversations about death to the forefront. As talks about human composting and mushroom burial suits went viral, media outlets began to feature stories on everything from green death tech, to death architecture, to the ways we think about (and let’s face it, avoid thinking about) our mortality. Here are a few of the most popular Ted Talks that focus on death and helped to spread the ideas of the Death Positive Movement.

Mushroom Burial Suit

The Infinity Burial Suit or “Mushroom Burial Suit”—a handcrafted garment worn by the deceased—was invented by Founding Order member Jae Rhim Lee who says, “The power of the suit is that it creates the need for meaningful planning and discussion around death.” While the suits are intended to aid and accelerate the process of decomposition, their effectiveness is questionable. They do carry out Lee’s original mission to foster important conversations about death, the environment, and subverting the offerings of a traditional funeral.

Learn more about green death tech.

Social Justice Issues

A core belief of The Order is that everyone should have access to their idea of a good death, however this is not possible when so many historically marginalized people disproportionately experience bad deaths. The movements and issues included here, among many others, are central to the work of the Death Positive Movement.

2013

Black Lives Matter

What began as a hashtag in 2013, started by three radical Black organizers—Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi—has now grown into what is believed to be the largest social movement in the U.S. The movement began as a response to police brutality and racially motivated violence frequently experienced by Black people in the U.S. The broader movement draws our attention to the countless ways systemic racism and white supremacy is not only directly responsible for centuries of preventable, unnecessary deaths of Black people but adversely impacts every facet of the Black end of life experience, from mourning to the erasure of Black burial grounds.

Learn more how the Death Positive Movement intersects with Black Lives Matter.

Feminism

While debatable which wave of the feminist movement we’re currently in, discussions of feminism were a major focus of 2017. Between the Women’s March, Tarana Burke’s #MeToo Movement, and much needed calls for the future of feminism to be intersectional, the fact that the Death Positive Movement was overwhelmingly femme-led resulted in prominent features on the role of women and death.

To learn more read the Yes! Magazine article The Story of Death Is the Story of Women.

Fetal Burial Legislation

In recent years there has been a resurgence of bills that would legally require patients to treat fetal tissue in much the same way we treat deceased persons. This typically involves contracting a funeral home or crematory, arranging for cremation or burial, receiving the “remains,” etc. This not only places a terrible financial and mental health burden on patients, but also lines the pockets of the funeral industry and makes it challenging for sexual and reproductive health care clinics to operate.

This article on Rewire News Group states: “Fetal burial laws invoke an even more nuanced obstruction to care by playing into the country’s largely death-phobic nature. Death-phobia is more than just the fear of death and dying: It’s a culture of shame and stigma surrounding death and end of life that breeds anxiety and misunderstanding.” All things the Death Positive Movement works to counteract.

To learn more go to our Fetal Burial Resources.

Femicide: Ni Una Menos, Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women

Across the globe femicide has reached epidemic proportions, particularly across the Americas. In Mexico ten women are murdered each day. In the U.S. and South America, femicide has been increasing at alarming rates, and in Canada where Indigenous women and girls make up only 4% of the female population, they make up 16% of all female homicides. Simply existing in a feminine body places those individuals in closer proximity to death.

Learn more in our article The Life and Death Of Stolen Sisters.

Transgender Rights

Between the increase in fatal violence against Transgender people, their civil rights being restricted or eliminated, and challenges to accessing lifesaving physical and mental healthcare, all these and more are a direct correlation to the increase in attempted or completed suicides among Transgender people. In result, many in the Trans community are deeply concerned about their identity being erased in death through misgendering or deadnaming. This is a prime example why a tenet of the Death Positive Movement is that the laws that govern death, dying and end-of-life care must ensure that a person’s wishes and identity are honored.

Learn more about transgender rights issues.

The Cemetery as Cultural and Community Space

Over the past decade there has been a movement toward cemeteries being more than just a final resting place for the dead, but a cultural and community hub for the living. For many cemeteries, these efforts are a return to their once intended use as a public park space when some cemeteries served as a popular destination for leisure and community activities. We’ve seen a boom in innovative programming recently including movie screenings, yoga classes, and tours that highlight and center the history of women, as well as Black, and queer communities. These events can provide a fun and non-threatening way for people to engage with death, while providing much needed funding for the preservation of these historic spaces.

Learn more in this Smithsonian Magazine article From Yoga to Movie Nights: How Cemeteries Are Trying to Attract the Living.

Books

In the past decade an unprecedented number of books about death have hit our shelves. Here are three best sellers that had a huge impact on advancing the movement forward.

Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End by Atul Gawande

Gawande, a practicing surgeon, addresses his profession’s failings when confronted with the end of life and advocates that quality of life should be the focus for physicians, patients, and their families in the face of death. The book inspired an Emmy nominated documentary in which Dr. Gawande explores death and why doctors struggle to discuss death with their patients.

Learn more about Being Mortal.

When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi

On the verge of completing a decade’s worth of training as a neurosurgeon Paul Kalanithi was diagnosed with stage IV lung cancer. His book explores questions such as: what makes life worth living in the face of death? And, what do you do when the future, no longer a ladder toward your goals in life, flattens out into a perpetual present?

Learn more about When Breath Becomes Air.

Smoke Gets in Your Eyes: And Other Lessons from the Crematory by Caitlin Doughty

In her signature poignant and humorous style, mortician Caitlin Doughty lays bare the workings of the funeral industrial complex, and exposes how our fear of death has shaped western culture and the way we treat our dead.

Learn more about Smoke Gets in Your Eyes.