Tell us about your work, Kelly.

I am a writer and artist. I am interested in so many components surrounding death, but many of them come together under the umbrella of social history. I am deeply interested in how we, as human beings, respond to death and loss in large scale ways. Cultural responses to death fascinate me. A large part of my current writing and research explores how death was imagined and managed in the 19th century United States, an era where shifts in medicine, capitalism, and religious practices (among many other spheres) allowed for death to be revered as both a spiritual milestone, social experience, and natural component of life. I am fascinated by this, especially because contemporary mourning culture is practically non-existent. I strive to create space for a more comprehensive and cohesive dialogue surrounding loss, mourning, and death in our current landscape. I use writing as a tool to bring historical moments and events into conversation with modern theories on how and why we make sense of things in the way we do when it comes to death.

I am also interested in highlighting the ways that power is always at play, even in our darkest moments. At my most ideal, I imagine that creating thoughtful work around death and having conversations about it allows us to build bridges to people who we may not otherwise build relationships with. If we consider the many political divides that disrupt families and communities, perhaps a dialogue about the one thing that we all experience would bring us together. I want to have conversations about what it feels like to mourn and what it feels like to prepare for your own death with people I may otherwise not be able to connect with.

After experiencing a sudden loss at the age of 17, I felt extremely isolated while trying to make sense of what had happened. In the following years, I became extremely interested in how I could find ways to ensure that other folks felt more supported while grieving. This has come out in many ways. As an avid anti-war protestor in the early 2000s, I started photographing military funerals for fallen soldiers to document a national loss that was both illegal and going unnoticed. Despite my own feelings on the war itself, I was able to create meaningful relationships with the families of those burying their sons and daughters. They let me into their lives at their darkest moment, and it completely changed how I wanted to go about getting to know folks who have different experiences than I do. We all mourned the same.

Beyond this, I completed my work in graduate school about mourning photography and its unnoticed importance. This has led me to writing, photography, and new media projects in the last several years, which has been extremely fulfilling and has shaped how I approach my day to day life as well.

What are you working on his year?

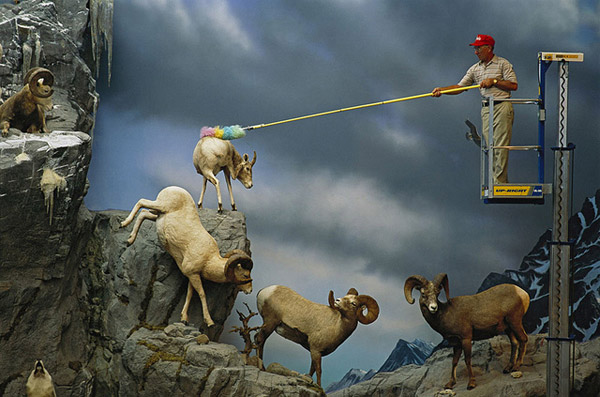

I continue to write a bi-monthly article for an online publication, Dilettante Army. I love writing for them because they allow me to dive into anything that I’m feeling an itch for. My editor, Sara Clugage, is always supportive of my more macabre projects. I feel very lucky to write for them. I am currently working on some longer form work on the social history of bodily preservation, both human and animal. I’ve started some preliminary research and writing, but look forward to carving out some more time and energy for it. That writing ties together some of my photography that I’m currently working on. I am documenting forgotten or unsupported taxidermy dioramas that are no longer being kept up in museums. There are many museums, many are smaller institutions – that don’t know how to support the preserved animals, have new buildings that they couldn’t be moved to, or have replaced old dioramas with newer exhibits. I hope to highlight how taxidermy can be an entry point in how we think about death, because it is familiar and accessible to many.

What does death positivity mean to you?

Death positivity means creating and maintaining dynamic and honest dialogues surrounding death, mourning, and loss in contemporary culture. Being open and finding a sense of positivity and growth in our conversations and work surrounding death is crucial for building empathy and understanding. It can be very isolating to encounter the death of a loved one or in thinking about ones own death, and my hope is that by making work around death will allow people to interact in a more open and supportive ways. I think that some of the anxiety we come up against in doing death positive work could be alleviated if there was simply more room to make sense of death openly with folks in and outside of our communities.

What other death-related job that you don’t have, would you want?

I would love to be a forensic anthropologist. I am so intrigued by how our bodies can share information about us, even after we die. As someone who is driven by research and problem solving, forensic anthropology would certainly be an enticing career choice. I do daydream of going back to school and seeing if I could tackle the science requirements. In the mean time, I’ll just have to read about the amazing work of actual forensic anthropologists.

When you die, what do you want done with your corpse?

I want a very low-key green burial. I prefer that my body just go back into the earth. It would be great to have my body become part of the rest of the world; parts of trees, the air, fresh soil, sustenance for life. I don’t want to take up room or resources; I’m not overly fond of embalming for this reason, although I do understand its appeal. I would hope that in lieu of a traditional funeral, there would be an epic party for all of my friends and family to share stories and spend time together.

Kelly has written some wonderful pieces on death and photography for The Order, like A Shocking Likeness: Photography and Death in the Civil War, and The Unpleasant Duty: An Introduction to Postmortem Photography However, our favorite pieces of hers delve into problematic social and cultural issues, such as the death and burial of individuals who have committed horrific acts, the legacy of lynching and visual culture (tw for violent images), and Re-enacting Whiteness.

You can read more of Kelly’s work on her website, and follow her on Twitter.