In early 2013, an unusual journey took place. That February, the remains of a nineteenth century performer known as “the Ugliest Woman in the World” were removed from storage at the University of Oslo and repatriated to the Mexican state of Sinaloa, where they were given a dignified Catholic burial.

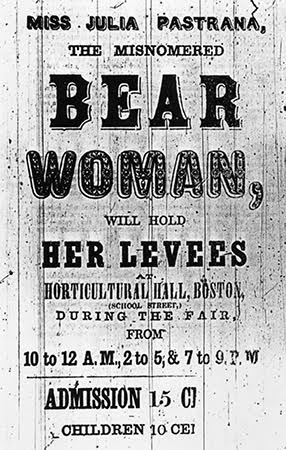

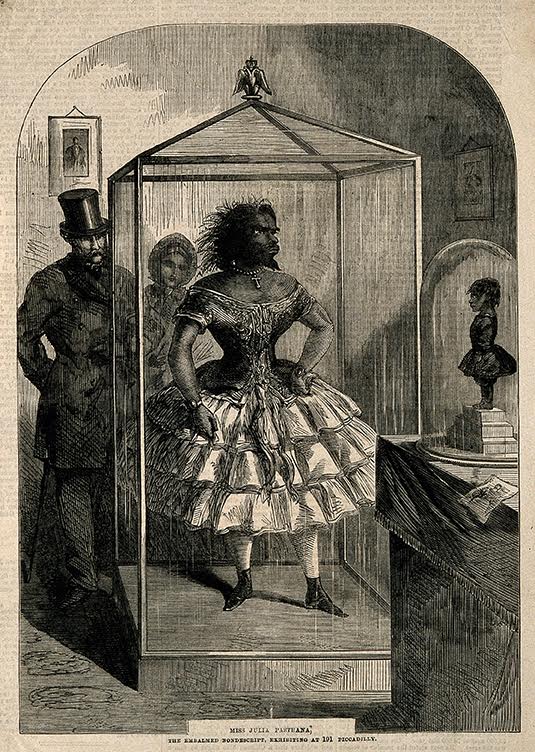

A gifted singer and dancer, Julia Pastrana was born around 1834 with an unusually pronounced jaw and thick hair throughout her face and body. Though by all accounts an extremely pleasant person, her physical characteristics drew frequent comparisons to bears and other beasts. Her husband-manager exhibited her throughout Europe and the United States as “The Bear Woman—Half Human, Half Beast.” After her death in 1860, her embalmed body and that of her infant son were exhibited for over a century, appearing as late as the 1970s in US fairgrounds. They later spent decades in storage in Oslo, where they were vandalized, and her son’s body eaten by mice.

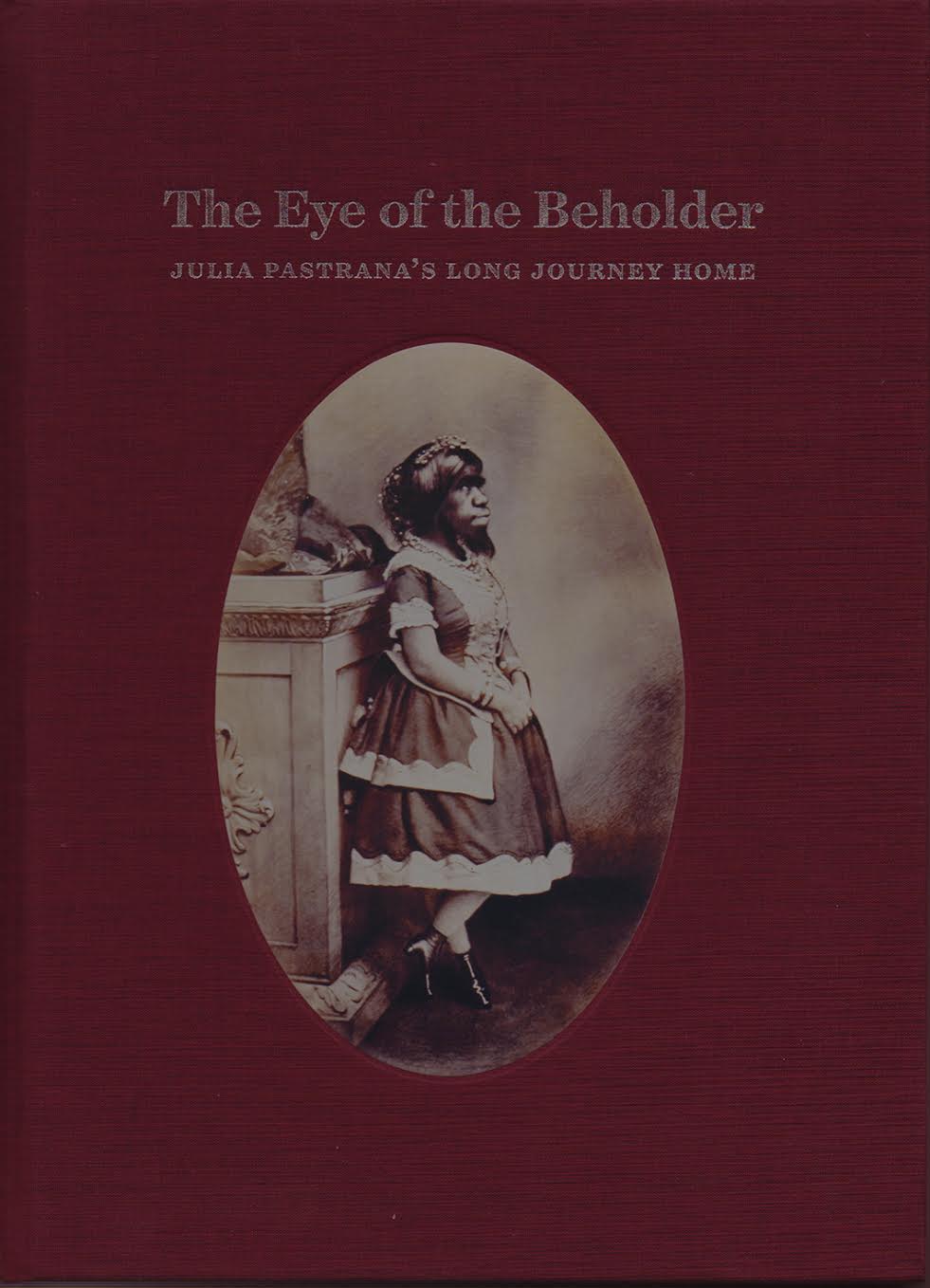

In 2013, after nearly a decade of effort, artist Laura Anderson Barbata succeeded in having Pastrana’s body repatriated to Mexico. The act drew worldwide attention as a measure of justice for Julia, as well as a small but symbolic triumph for human rights and women’s rights. As someone who has written about Pastrana, I was deeply impressed by Barbata’s tenacity in standing up to nations and institutions to accomplish her goal, and I wanted to ask her how she did it. A few months back, we spoke in honor of her new book The Eye of the Beholder: Julia Pastrana’s Long Journey Home (to which I also contributed). As we sat by the banks of Brooklyn’s Gowanus canal, we talked about the responsibility we bear to our dead, and the transformative power acts like repatriations can hold.

This interview took place on May 21st, 2017 and has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Bess Lovejoy: So how did you first discover Julia’s story?

Laura Anderson Barbata: I learned about the story of Julia Pastrana through my sister, Kathleen Culebro, who was producing a play here in New York—TheTrue History of the Tragic Life and the Triumphant Death of Julia Pastrana, the Ugliest Woman in the World, by Shaun Prendergast. She asked me to design the visuals for the first few minutes of the play, because the play basically unfolds in the dark. My sister had seen the play in London with my mother and they were affected by it, they felt it was an important story and they were shocked they’d never heard anything about her, being Mexican.

I was horrified and saddened just like everybody in the audience was, and my sister started a petition [to be] sent to the Mexican embassy in Oslo, requesting that Julia Pastrana be repatriated to Mexico and buried. Everyone who left the play signed it, it was sent, and that was it. My sister never received an answer.

BL: How did you go from being interested in her story to deciding to act yourself?

LAB: I signed the petition, but signing a petition isn’t enough. The play ended with Julia speaking to us from the basement of the Schreiner Collection [at the University of Oslo], where she was being stored. Sometimes it’s not enough to feel empathy—you have to actually act, right? I think that’s the purpose of empathy—it’s a driving force for activating change.

Because of my work in the indigenous communities of the Amazon, I was offered an exploratory trip to the north of Norway, where the Sami communities live, not long after the play closed. The Sami had been involved in repatriation efforts themselves with the Schreiner Collection, which has thousands of Sami skulls that were obtained illegally. So this was happening at the same time I was thinking about Julia Pastrana, and I observed what the Sami did and how the government responded.

This research continued when I returned home, but much more focused. A short while later, I was awarded an artist in residency in Oslo by the Office of Contemporary Art.

BL: Who was the first person that you broached this with?

LAB: Dr. Per Holck, the curator of the Schreiner Collection. I wrote to him and said that I was interested in learning more about Julia Pastrana. And his answers were defensive—he said, “you can’t see her, she’s treated better than she would be in a church,” etc. I found his response strange: I never asked to see her, I simply asked a few very specific questions about her: why is she there, has anybody asked to see her, has anybody asked to do any tests? The official response was that “she’s there to serve science,” although no research had been done, nobody has had access to her, and no one had petitioned to see her.

BL: So who did you go to after Dr. Per Holck?

LAB: I went to the University of Oslo ethics department. They explained how the collection came to be built and how it operates . . . meanwhile, I was gathering information: reading, meeting people, having conversations.

I also knew that I had to be very careful because these issues are sensitive on many levels: it could have been an avalanche for institutions and museums to consider how they handle their own historical collections and mummies. So I knew that I had to be very careful and specific in order for the doors not to shut.

I was really just trying to understand the situation, but people around me were hoping that I would be able to accomplish the repatriation. Thanks to my friends, this happened. Every time I saw them they’d say, “Well, how’s it going?” They wouldn’t let it go. I felt exhausted, completely demoralized by the slowness, the complications, the bureaucracy of just trying to find out the facts.

BL: What were some of your next steps?

LAB: The National Committee for Research in the Social Sciences and the Humanities [NESH] didn’t know how to address the situation, so they decided to start a new board made up of citizen volunteers to review cases of the treatment of people after they’ve died … and Julia Pastrana became the first case for the board. They said that I could submit my letter as soon as the board was formed, but it took them two years to get organized. In the meantime, I had left Norway and I began consulting with experts about what to include in the letter, and I was doing as much research as possible.

BL: Was there one thing that you found specifically useful when you were learning about repatriation? One specific case?

LAB: Sarah Baartman [an eighteenth century South African woman exhibited as the “Hottentot Venus” in Europe whose remains were kept in a French museum for many years before being repatriated in 2002] was really important to me. Her case taught me many things at different moments. Initially, she was important as an example of a successful case, and that was encouraging. I could approach officials in Mexico and say “Well, Nelson Mandela intervened to get Baartman repatriated,” and that was proof that these efforts are important.

BL: So was the next step that the board actually convened?

LAB: Yes. I sent my letter and received a note that they [NESH] received and reviewed it. But the correspondence was sent by mail and it was lost; it arrived about one year later inside a plastic bag with a little note from the USPS that said “sorry that your mail was damaged.” So I just had to remain super-optimistic and focused on the issues at hand.

I was at the mercy of institutions that deal with objects, and I stayed focused on treating Pastrana as an individual. I started to do very simple things: I published an obituary in the local Norwegian newspaper because I’m sure she didn’t have last rites or an obituary.

And since she was a practicing Catholic, I went to St. Joseph Church in Oslo and explained her story and that of her baby. I asked if they could have a mass in memory of her. The priest said, of course, let’s do it. He said, “She’s a child of God, she needs this.”

LAB: So these restorative acts were very simple, but they began to change the chemistry of the relationships, and the way people saw her. When an audience walks out of a play, they may be moved and feel empathy, but they also feel powerless. But through simple acts it’s possible to change perceptions—from pity to dignity. And you start building on that, and helping people to feel that they can contribute to that. Otherwise, if we all wait for petitions, nothing’s going to change, we need to start changing things within ourselves and around us.

BL: So did the board ever get going?

LAB: Yes, they were great. Essentially the letter in the plastic bag said: yes, we agree that Pastrana would not have wanted to be in a collection. But you have no claim on her, because you are not related to her, so thank you very much.

So then I thought, well, no problem, I’ll find a relative. There are many cases of hypertrichosis in Mexico and there’s an institute devoted to it. So I went to meet with them and they said it’s impossible to find a relative because we don’t have her DNA. No research had been done on her, there was not even a DNA sample.

And then I thought, but why do I have to be a relative to say that she should be treated with dignity? So that answer helped me, and I started articulating my whole approach from that perspective. This negative answer was the most positive one, because it’s very hard to debate our responsibility toward others.

BL: Meaning once you broached that argument, they weren’t able to shoot it down?

LAB: Right, because I was able to prove that people care, and it is our duty to defend the rights of others, especially those who don’t have a voice. This responsibility is not restricted to blood relatives only.

BL: What did they say?

LAB: Well, then a reporter from the Mexican newspaper Reforma, Silvia Gámez, became involved. At first I was cautious: I knew the story could become very political in Mexico. As a journalist she had to maintain a neutral position, but she broke the story in Mexico and it was one of the most widely read stories in the country, and was picked up by newspapers all over the world. This helped to prove that there was interest in Mexico.

And finally the NESH board said ok, we’re only an advisory committee, and we can’t demand that the university and the Schreiner Collection return her, but we can make a recommendation. And the Ministry of Health, who had initially made the recommendation that Julia go into the Schreiner Collection, also accepted the idea.

Meanwhile, I realized that I needed to make an even stronger case—I need somebody behind me … I needed my Nelson Mandela. I decided to approach the governor of Sinaloa because Julia Pastrana was born there. Sinaloa is a state that needs a positive story, since it has one of the highest rates of violence in the country.

BL: And you are from there?

LAB: I’m from Mexico City but I grew up in Sinaloa—I spent my childhood there, so I have a very special love for it. I contacted a historian, Ricardo Mimiaga, who was the only person I knew of who had done any research on Pastrana, and we went to see the governor of Sinaloa together. We asked him to write a letter to the board, as a representative of Mexico, and [saying] that in his official capacity he is requesting the repatriation of Julia Pastrana.

Everyone agreed—the board and the university, but the governor couldn’t be involved further because international relations are the responsibility of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. So the governor of Sinaloa made a formal petition, requesting the intervention of the embassy of Mexico that serves Norway—which is located in Belgium serving several countries.

And there’s another important point—Julia did not have a death certificate, so she couldn’t be handled as a person by a funeral parlor, or transported. Legally funerary services cannot do anything without a death certificate.

While I’m still organizing all of these details, I contacted a repatriation service. The university decided to have a ceremony for her, and this is a very important moment: it shows that they recognize the importance of treating her as a human being after being treated as part of a collection for so long.

And at the same time the Cultural Department in Sinaloa was preparing to welcome Julia, and part of that involved local funerary services, and addressing questions like where is she going to be buried, what kind of cemetery, is it protected, is she going to be robbed again? All these issues had to be solved.

BL: Just to go back for a minute, how does the actual “yes” come about? Who makes the final “yes,” if there is one?

LAB: The actual “yes” was from the university after they received the formal petition from the governor of Sinaloa, as well as a letter from journalist Silvia Gámez, a letter from me, the recommendation by NESH, and I understand that they also received one from Dr. Per Holck. The university agreed to the repatriation, but with some conditions: she should never be exhibited again, she should be buried and not incinerated, she should be given funeral services following her faith. Those were the conditions. And I thought: those are the best conditions, those are my conditions too! This is amazing.

I’m sure this was a very challenging process for the university. At the Anatomical Institute of the University of Oslo, Nicholas Márquez-Grant [forensic anthropologist, Cranfield Forensic Institute] and I, representing Sinaloa Mexico on behalf of the governor, confirmed that it was Julia Pastrana and witnessed as she was placed in her official coffin. Julia Pastrana was then transported to a private ceremony hosted by the university, at which the chancellor spoke with great respect and emotion.

BL: And then her coffin was put on the plane?

LAB: Then her coffin was put on the plane. I wanted to accompany the coffin at every step because I was worried about what could happen, especially without a death certificate. But Albin International Repatriation company coordinated every detail perfectly.

She went from Oslo to Paris, then Paris to Mexico City, Mexico City to Culiacán—the capital of Sinaloa. They had a military arrival for her, and then she was driven to the military base, where a press conference was held followed by a small memorial. The following day, she was transported to Sinaloa de Leyva, where she was buried.

There was a reception ceremony, and a lot of people came from neighboring communities, and there was a lot of press coverage. One of the most surprising things to me was the ways in which people responded to Julia and the signs they carried: such as “No more Julia Pastranas.” Her story also resonated with the violence against women and the missing women in Mexico. They connected Julia strongly to indigenous rights. The indigenous communities wanted her to be buried in their cemeteries, and while it’s true, she should have been, those cemeteries don’t have protection. They are at the center of a very problematic area in the state of Sinaloa, drug cartels are very strong and driving there is dangerous and difficult. It took some time to find the right cemetery that was close to where she was born, but was also secure.

So at the burial there’s the welcome committee, the governor spoke, and then everybody walked—this is a tradition—with the hearse and her coffin to the church for her funerary mass and afterwards continued the walk to the cemetery following a loud Sinaloan Tambora band to the cemetery where she was buried. I had started a campaign so that flowers could be sent from all over the world, but I never expected a truck full of white flowers for her. There were so many that they didn’t fit!

BL: What were some of the main things that you learned while doing this?

LAB: That justification for doing the right thing is our connection to other people, our humanity, not national or DNA connections. I already knew that, but it’s much more powerful than we give it credit for. And we need to really remember that.

But there’s a couple of other things that I think are really important: one of them is that you can, from wherever you are, make a difference. And it can take a long time, but you can contribute, and I think it’s our responsibility to contribute and correct injustices done in the past because we’re also paving the way for the future so that it doesn’t happen again—and that’s really why you do it.

And through this, you can enlist people into the opportunity. I think that’s the really important thing, making people feel like they’re part of this.

BL: Is there anything else you feel like you would want to say right now, in telling this story?

LAB: Your chapter outlines a couple of individuals that really do need to be repatriated. Nicholas Márquez-Grant, a forensic anthropologist, takes these questions on in the book and he admits that he was worried because a lot of his colleagues are against repatriation, because it means that an avalanche of bones are going to have to come out. But it doesn’t mean that. His text says you have to look at each case individually. I think they should not be forgotten and must be seriously evaluated.

BL: So what would you say to somebody who wanted to try to do something similar?

LAB: My recommendation is to approach it first with humility, it’s a complex issue. We don’t understand all of the systems that are operating, and we don’t want to close any doors. I think that’s the healthiest way, to be transparent and say: “I want to understand the situation. I feel a certain way about it, but I’m willing to suspend it to listen to you.” And then keep on learning from that. And persistence is good, surround yourself with people who believe in what you’re doing, sometimes more than you do.

Bess Lovejoy is the author of Rest in Pieces: The Curious Fates of Famous Corpses (Simon & Schuster, 2013) and an editor at mental_floss. She often writes about burial grounds of marginalized people, repatriated bodies, the history of bodysnatching in the U.S., and celebrity entrails.