Embalmed Alive! is Episode 6 (Season One) of the Death in the Afternoon Podcast.

Episode 6: Embalmed Alive!

Embalming. It sounds like the stuff of horror movies: pump a dead body full of chemicals to make it look alive—ALIVE! Whose idea was this? Is there really such a thing as “extreme embalming”? And what about when embalming (allegedly) goes horribly, horribly wrong? We discuss these and other questions on this week’s episode of Death in the Afternoon.

This week our intrepid mortician and researcher pick apart another current event, from 2018, “Russian woman embalmed alive in deadly hospital mistake.”

Indeed. She does.

Caitlin and Louise also discuss another subject we get frequent emails, asks, and comments about at The Order—extreme embalming, posing an embalmed corpse in a “life like” pose. Here’s Louise with a bit more about this segment:

When I was working on the section about “extreme embalming” as Caitlin calls it, I was struck by why Angel Luis Pantojas wanted to be embalmed and posed standing at his funeral.

Most publications give little mention as to why Pantojas wanted to be standing. Honestly, I don’t know all the details. But from what I gather, at six-years-old Pantojas stood at his murdered father’s open casket and essentially said, “This is not how I want people to see me. I want people to see me on my feet when I’m dead.”

It’s a staggering moment for anybody, but especially for a child. Growing up amidst guns and violence in San Juan, Pantojas did not get the gentle exposure to death and dying that so many of us wish for our children. It’s a privilege to approach death on your own terms, not the other way around. At such a tender age Pantojas not only had to confront the reality of death, but he also made a decision as to what he wanted for his death.

At six, Pantojas told his family that’s what he wanted and he maintained those wishes up until is death at age 24. I don’t pretend to know his family, but I wonder how such a declaration was taken from a child? I think about if my young niece told me this. Would I receive it with humor? Gravity? Would this death plan formed in the obstinance and innocence of childhood be binding? Would I hold her wishes dear to me and solemnly promise to adhere to her plan?

Of course, my niece lives in a world where her childhood is sheltered from gunshots and harshness. Her worries are of the chickens in her backyard getting along and what Grammy might give her for Christmas (and Hanukkah).

I’m not sure that’s the world that Pantojas grew up in.

Angel Luis Pantojas died brutally. He was “shot 11 times, twice in the face, and tossed over a bridge in his underwear.” He died an adult with the funeral wishes of a child.

Maybe that’s not fair to say. The way he wanted to be dead evolved, even if the idea was planted in his youth. He told his family he wanted to be on his feet, seen as strong, he didn’t want to leave the world lying down. To their credit they honored this.

I don’t pity Pantojas. My heart aches for a life cut short. I also don’t want to cast a sentimental haze over a society plagued by violence. Pantojas did not die gently and his death plan was not gentle either. It was defiant.

No matter what my personal beliefs are on embalming as a routine practice, I’m happy that Pantojas and his family had the option to pose his body standing, el muerto parao.

Miriam Burbank at her funeral.

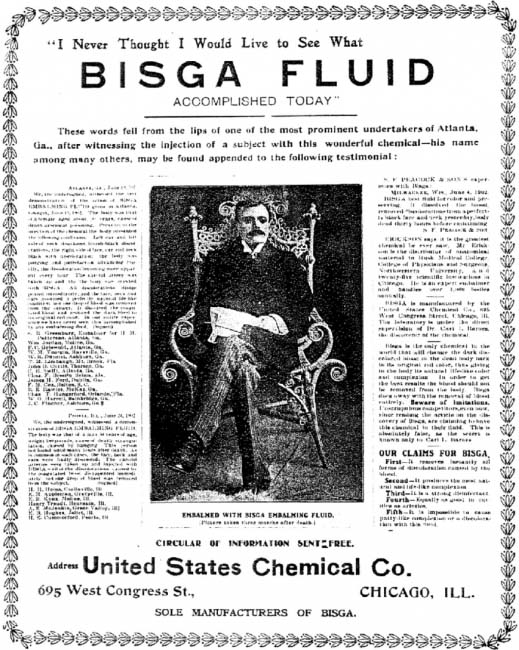

Extreme embalming is not exactly new, as Sarah tells us in her segment about the Bisga Man:

The Bisga Man is another story I’ve been wanting to tell for a number of years, but the idea that has always captured my interest is the concept that an embalmed body will provide mourners with a final “beautiful memory picture.” Something I hope listeners will take away from this episode is this reminder from Caroline Vuyadinov, that the “memory picture” is not the property of the death care industry:

“Memory pictures are those memories we hold dear of our loved one. They are the many memories we have of our loved ones who have died that bring us joy and make us remember just how wonderful they were. No industry can direct the memoires of our loved ones. I think if we all took the time to talk about death, and what we need to do at the time of death, our loved ones would be at the mercy of the “professionals” that present choices that fit their belief system but not ours. In this season, let us make memories of those we love, and take the time to express to those around us what we want as our final wishes.”

Episode 6 Transcript

[00:00:00] [B horror movie music plays.]

Caitlin: [00:00:12] Here, in this unassuming hospital, a place where doctors are supposed to make you better, one doctor… wants to make you DEAD.

[00:00:24] [Jump scare chord in the background music.]

Caitlin: [00:00:24] Terror stalks the halls, formaldehyde forced through your veins, you are a living corpse when you are…EMBALMED ALIVE.

[00:00:37] [Screams.]

[00:00:38] [Death in the Afternoon theme plays.]

Caitlin: [00:00:47] Welcome back to Death in the Afternoon, a podcast about all things mortal from The Order of the Good Death. I’m Caitlin, a mortician and death educator, and as always I’m joined by my fellow researchers and writers Louise Hung and Sarah Chavez. Today’s episode: EMBALMED ALIVE!

Louise: [00:01:06] At last we are finally talking about zombies!

Caitlin: [00:01:08] No… never. We will never be talking about zombies, Louise.

Louise: [00:01:12] [not missing a beat] —So today we are finally talking about that woman who was EMBALMED ALIVE. Though not-gonna-lie, I feel kind of bad making fun of her.

Caitlin: [00:01:21] I am not making fun of the woman who died, I’m making fun of the idea that she was EMBALMED ALIVE, which she was not.

Louise: [00:01:28] Okay, fine, maybe she wasn’t prepared for burial in the traditional sense, but isn’t a nurse accidentally pumping her body full of formaldehyde the basics of embalming?

Caitlin: [00:01:40] I mean, that’s sort of what embalming us. But more importantly, that’s not what happened.

Louise: [00:01:45] We’re about to go on another journey of debunking aren’t we?

Caitlin: [00:01:49] All aboard the killjoy train. I’m your conductor, Caitlin. Choo choo.

Louise: [00:01:55] This incident happened in March of 2018, a woman named Ekaterina Fedyaev went into a hospital in Ulyanovsk, Russia to have ovarian cysts removed. This was a routine surgery, theoretically nothing should have gone wrong.

Caitlin: [00:02:11] Spoiler for the squeamish, it does go wrong, and the story is very grim.

Louise: [00:02:16] Very grim. The original articles, even the ones in reputable news outlets, explained the story like this. Ekaterina’s nurse was supposed to put her on an IV drip of saline which is a solution of salt water used to replenish a patient’s fluids and electrolytes after a surgery. But instead, by some horrific accident, the nurse hooked her up to a bag of formaldehyde, which slowly dripped into her body.

Caitlin: [00:02:42] Now, the initial explanation for this makes it seem like hospitals just have bags of formaldehyde lying around that can easily get hooked up to an IV. And if the nurse isn’t paying full attention, you too, at any moment, could get embalmed alive.

Louise: [00:02:58] So hospitals don’t just have bags of formaldehyde lying around?

Caitlin: [00:03:03] No. Formaldehyde is a gas, actually. So, they don’t. But, they more likely had a formaldehyde solution, where formaldehyde is mixed with water and other chemicals. In this case it was likely formalin, which is a solution of 40% formaldehyde, extremely strong stuff. That’s a much higher percentage of formaldehyde than is used in an embalming solution at your local funeral home.

Louise: [00:03:26] So this situation would actually be worse than being embalmed alive?

Caitlin: [00:03:31] I don’t know if you can put in on a sliding scale. Any formaldehyde solution being directly injected into your body is too much. It’s like saying, “Do you have one shark eating your leg or two?” Any shark is too many shark.

Louise: Okay, so if formalin solution is being put through an IV drip into this woman, is she being embalmed alive?

Caitlin: [00:03:56] Sort of. Here is how embalming works. The embalmer first makes a cut on the dead person’s neck, and then opens up the carotid artery and the jugular vein. The formaldehyde solution is pumped by a machine through the artery which in turn pushes blood out of the vein.

[00:04:13] So, if the blood in the dead body is coming out, and the circulatory system is flooded with this formaldehyde fluid instead, it hardens and preserves the tissues of the body.

Louise: [00:04:24] So, Ekaterina wasn’t actually embalmed alive, but there are similarities.

Caitlin: [00:04:30] There would be, but again, again, that is not what actually happened.

Louise: [00:04:36] Did it happen at all? Or is it like guy who was cremated alive, a total hoax?

Caitlin: [00:04:41] No, unfortunately, Ekaterina Fedyaev is a real woman who did what sounds like a horrific death. And what comes out later, as the local reporting from Russia becomes more clear, is that during the operation, for her ovarian cysts, formalin was introduced to her abdominal cavity instead of saline. So, basically her surgical site was supposed to be lightly washed with this gentle saline solution, but instead it was washed with formalin.

Louise: [00:05:10] Eugh. So, what happened after that?

Caitlin: [00:05:14] Well, she didn’t die immediately—I would have wanted to die immediately—but she told her mother and doctors that she was experiencing horrible abdominal pain. Her temperature was spiking up and her doctors didn’t tell her mother what was going on. They were just frantically flushing out her abdominal cavity. So she went into a coma, she was moved to Moscow, her organs began to fail, and a few weeks later, of torturous weeks later, she finally dies.

Louise: [00:05:42] And wasn’t she having this routine surgery in order to become pregnant?

Caitlin: [00:05:48] Yes, as we’ve established, this story is awful.

Louise: [00:05:51] Ugh. This—I don’t know—this sounds like a hoax to me. Do you really think it’s true?

Caitlin: [00:05:55] I believe that it is, at least, this much less sensationalized version of the story. A minister of health from the district tweeted his condolences about what happened and apparently all the medical professionals involved were fired. And this is flawless proof but all of these people seem to be confirming this woman did die and this did happen.

Louise: [00:06:18] So, for the record, she was not embalmed alive?

Caitlin: [00:06:22] No, putting some formalin on a surgical incision does not an embalming make. But outlets like the Washington Post still have articles up with the headlines like, “This Russian woman was ‘embalmed alive.” But the phrase ‘embalmed alive’ is in quotes.

Louise: [00:06:41] Who is the quote from?

Caitlin: [00:06:41] Nobody knows! It feels like some article at some point said that phrase and everybody else from there just threw some quotes around it and ran with it.

Louise: [00:06:49] Like they don’t have to be exactly right if there are quotes around it?

Caitlin: [00:06:53] Right, so I’m going to write an article with the headline “Oprah Winfrey ‘eats children.’” But when I put ‘eats children’ in quotes I don’t have to prove in the article at all that children are being eaten or even say where that phrase comes from.

Louise: [00:07:07] I found an article that said, “Russian Woman Mummified Alive.” What does that even mean?

Caitlin: [00:07:11] That’s even worse! That’s even less true, if that’s possible. It’s like “Oh, was she kept in a natron salt solution for 40 days and then wrapped in some aromatic linen?” No. She was not mummified or embalmed.

Louise: [00:07:24] But it’s still weird that a nurse would wash her with the formalin, right? Why would that have been there?

Caitlin: [00:07:29] The only thing I can think of is that formalin is used in hospitals. Usually it’s used for preserving anatomical specimens. So, biopsies or tissues that a histologist—which is a tissue specialist—would examine later under a microscope.

Louise: [00:07:45] So, it’s not totally out of place, like an elephant or Mike Tyson in the surgery room?

Caitlin: [00:07:49] No, there could absolutely be formalin in the hospital room. Maybe it was in a specimen jar filled with liquid, and it was ready to receive a sample for further examination.

Louise: [00:07:59] So, has anyone ever actually been embalmed alive? To the best of your knowledge.

Caitlin: [00:08:05] I looked into it and there are some other cases of living people accidentally injected with formaldehyde solutions in hospitals settings. There is an academic article from 2009 called “Accidental intravenous injection of formaldehyde”

Louise: [00:08:21] Ooooh nooooo.

Caitlin: [00:08:23] That guy, who was 33 and having knee surgery, lived. But, there’s more.

Louise: [00:08:29] Because of course there is.

Caitlin: [00:08:30] Yes, in 1985 a photographer for the Miami Herald is having his eye removed because it’s cancerous.

Louise: [00:08:37] Which is awful enough on its own.

Caitlin: [00:08:39] Yes, and six hours into the operation they take the formaldehyde-like solution that was meant to preserve the cancerous eye, and accidentally inject it into his body instead. And this man, Bob East, is not so lucky as knee surgery guy, and he dies shortly after.

[00:08:57] And this is a real quote from an article in the New York Times: “No one could figure out what had gone wrong for another hour, when the ophthalmology resident returned to the operating room, asking: ‘Where’s my glutaraldehyde?’

‘Oh My God’

The doctor froze. At that moment I realized what had happened, and I just screamed: ‘Oh my God! Oh my God!’ he later said.”

Louise: [00:09:23] Nooooo. Ugh, that story is so close to Ekaterina’s story. Is this a thing that happens more often than we think?

Caitlin: [00:09:33] Here’s what I think happened. All of these cases are medical error, where formalin that is supposed to be used to preserve a specimen is mixed up with something else routinely used for surgery. And the only reason Bob East’s—that’s the cancerous eye guy’s—case got so much attention is because he worked for a major newspaper for 30 years.

Louise: [00:09:54] Just like Ekaterina Fedyaev got so much attention because she was young, beautiful, and allegedly “embalmed alive.”

Caitlin: [00:10:01] I think that’s correct. Russian medical malpractice would never get reported if it didn’t have that sexy hook like, “embalmed alive.”

Louise: [00:10:09] Which was never true to begin with.

Caitlin: [00:10:11] Which was never true… to begin with.

[00:10:14] [Music plays.]

Caitlin: [00:10:24] There’s nothing I love more than the colonial American corpse. Back in a simple time when a corpse was allowed to be itself. After a few days in the family home, sure, the body may experience some light bloating, sunken eyes, faint smell. That’s how you knew the person was really, truly dead. But the rise in preservation and embalming changed how Americans saw the dead body, and just how alive it should look. Here’s Sarah Chavez.

Sarah: [00:11:00] Modern embalming began with the American Civil War, and the soldiers dying far from home. The young men were so worried about their bodies being left on enemy soil, that some even prepaid for the embalming procedure should they die on the battlefield. Then, after his 1865 assassination, President Abraham Lincoln was embalmed, his body going on a corpse tour by funeral train, stopping at 180 cities, an embalmer tagging along to do “touch-ups” on the body, as needed.

[00:11:35] By the dawn of the 20th century, a corpse did not have to look dead. Actually, it was preferred that it didn’t—well, at least until it was out of sight and underground. And as the unpleasantness of death was further disassociated from the corpse, things got downright uncanny.

[00:11:56] Soon enough, training and selling embalming fluid to a new breed of funeral directors was big business. In the January 1903 edition of The Sunnyside—a funeral trade rag with a disarmingly cheery name—a huge ad was printed featuring a photograph of a man casually sitting upright in a chair at its center. His legs are crossed, and he’s holding a newspaper in his hand, his mustache is neatly trimmed, and he appears to be dressed for a day out on the town. Without the caption that reads “EMBALMED WITH BISGA EMBALMING FLUID (Picture taken three months after death),” you might never know he was dead. Only upon a close inspection of the black and white image, would you notice the vacancy of his eyes, or the odd way one leg pushes at an uncomfortable angle against the fabric on the floor of the photography studio, would you even guess that his newspaper reading days are long behind him.

[00:13:06] Bisga embalming fluid was marketed by Dr. Carl Lewis Barnes, whose own mustachioed face appears in the upper left corner of the ad, alongside the following declaration: “I want to say a few words to the American Funeral Directors and Embalmers.” He explains that six months ago, he made several gallons of Bisga embalming fluid, based on three years of laboratory work. He boasts that it was “a chemical which would not only remove discoloration if present, but would combine with the dark discolored blood and restore it to its natural color, thus removing every vestige of discoloration and thus give to the body a perfectly life-like appearance.” He chases his claim with the rather morbid boast: “If you saw it remove the discolorations from the face and neck of a man who hanged himself, wouldn’t that make you think that you would like to have some?” And some, meaning the fluid, could easily be acquired, by writing a postcard to the United States Chemical Company in Chicago. Or, better yet, attend one of his upcoming exhibits of his “specimens” in Pittsburgh, Baltimore, Boston, New York, or Buffalo.

[00:14:31] The Bisga man was more than a corpse, he was a “specimen,” or, more accurately, an advertisement. There is no name of the Bisga man, no photograph of him in life. He is an object for fascination, and in being “saved” from the fate of mortal decomposition, he is no longer a person at all.

[00:14:56] Before debuting this sideshow of an embalming tour, Barnes authored the extensive 1898 book, The Art and Science of Embalming. In it he acknowledges all the reasons that embalming was being practiced so extensively in the United States, such as the rise of germ theory, and the idea of “disinfecting” the body, something he would have been particularly interested in, having served as a sanitary officer in Chicago during its recent yellow fever epidemic. He also recognized the use of embalming to preserve bodies for identification, and its purely aesthetic uses: “You can take a face which is showing age and make it look younger,” he writes. “You can take away the traces of pain or suffering from the corners of the mouth, and put a smile in its place. You can actually do what face powders and lotions claim to do (but cannot), restore youth to the face and bloom to the cheek; and the principal aid to success in this is, work, trial, experiment; you do not know what or how much you can do until you try.”

[00:16:19] Indeed, there seemed to be no limits to what embalmers were willing to try in their quest to stop time. Barnes was not the only turn-of-the-century practitioner to use actual bodies as advertisements. Thomas Holmes, known as the “Father of Modern Embalming” for his work on thousands of bodies during the Civil War, propped up preserved human corpses like mannequins in his DC storefront windows.

[00:16:48] The 1870 directory of the industries of Pittsburgh includes a listing for undertaker, W. H. Devore, whose embalmed subjects have been, quote, “kept for a period of ten years in the most perfect state.” He reportedly kept around two decade-old mummies to prove these embalming skills.

[00:17:11] Then, there’s Henry “Speedy” Atkins, a Black Kentucky tobacco worker, who drowned in the Ohio River in 1928. Without a family to claim him, undertaker A. Z. Hamock, who had a fascination with Egyptian mummification, used Speedy to test out his own embalming technique. An action that has a long history of medicine and science using the bodies of people from the most marginalized and vulnerable communities, without consent for their “experiments,” all in the name of progress.

[00:17:51] Hamock must have been so pleased with the results that he saw burial as a waste, so Speedy was displayed in the funeral home, becoming something of a tourist attraction as visitors asked to see the body with its weathered skin, which was kept standing upright in a closet. Speedy was finally buried in 1994, in a grand funeral attended by 200 people. His tombstone reads: “Lived 51 years as a pauper… buried 66 years later as a celebrity.”

[00:18:29] The obsession with understanding and preserving the inner workings of the body that drove Barnes and these other embalmers continued into the 20th century, with embalming and the presentation of a life-like corpse still the norm today at American funerals. With calm expressions and rosy cheeks, these corpses recline in caskets cushioned with soft mattresses, their heads resting on lacy, satin pillows. All of these come together in what’s called in the funeral business a “memory picture,” intended as a last, peaceful, uncorrupted look at the dead as a kind of closure.

[00:19:20] [Music plays.]

Caitlin: [00:19:25] Sarah Chavez…

[00:19:28] It was always interesting to me when I was in mortuary school, where they train embalmers, that the new way to describe embalming is that it gives a natural appearance.

Sarah: [00:19:38] Not lifelike?

Caitlin: [00:19:40] They don’t want to use lifelike anymore for several reasons. One it’s creepy, and two the embalmed body doesn’t really look lifelike. There were all these older textbooks and handouts we used in school where the term lifelike slipped through though, so the term is still very much a part of the fabric of funeral service. Which makes me sound like a trade magazine, “embalming is still part of the fabric of funeral service.”

Sarah: [00:20:07] But also, no embalmer today would claim that their methods would preserve the body for decades, or would display an embalmed corpse in their window as an advertisement.

Caitlin: [00:20:18] They couldn’t legally do either of those things.

Sarah: [00:20:21] But you still see what remains from this period—the obsession with the stopping of time, the erasing of pain, and the denial of death.

Caitlin: [00:20:30] Presenting the body as something more alive than dead.

[00:20:33] [Music plays.]

Louise: [00:20:55] So Caitlin, tell me, how do you envision your memory picture?

Caitlin: [00:20:59] My corpse look, you mean? Well, obviously my bangs will look flawless, there will be a pretty organic cotton shroud, my body elegantly laid out, perhaps some taxidermied animals set up around me like a dark tea party, and obviously, I’ll be unembalmed and ready to decompose. And maybe the whole thing will be livestreamed for YouTube because why not. Death positive.

Louise: [00:21:21] How much of that is a joke?

Caitlin: [00:21:23] Is any of that a joke, though?

Louise: [00:21:26] Okay, well. There are funeral directors out there who could make your tableau dreams come true.

Caitlin: [00:21:32] That’s right, we’re talking about extreme embalming. Which has always been a favorite title of mine. It sounds very early-oughts. Monster Energy Drink! X-TREME EMBALMING. But it’s actually the sort of sensible, correct name for it.

Louise: [00:21:47] Yes, that’s true. At the Charbonnet-Labat Glapion Funeral Home in New Orleans, Louis Charbonnet has made a name for himself arranging his clients in life-like post-mortem tableaux.

Caitlin: [00:21:59] Their iconic work of corpse art was the woman posed with a beer and a cigarette.

Louise: [00:22:03] Sure was. That was Miriam “Maw Maw” [Pronounced “May May”] Burbank. At her 2014 funeral, her family asked that Charbonnet sit her embalmed corpse at a table holding a menthol cigarette, drinking a Busch beer, and surrounded by a few of her favorite things—like New Orleans Saints football paraphernalia, the scotch she occasionally liked to sip, and a disco ball. Maw Maw was just staged chilling in what looked like a living room and presiding over a house party rather than a funeral.

Caitlin: [00:22:34] Is this a regular thing for Charbonnet’s funeral home? Do they do services like this all the time?

Louise: [00:22:38] I think it became a regular thing. Just recently, the funeral home actually handled the funeral of Renard Matthews, a young man who loved video games and the Boston Celtics. So, for his funeral, Matthews was sat upright in a “gaming chair” holding a Playstation controller, surrounded by his favorite snacks, and with the Celtics playing on the TV.

Caitlin: [00:22:59] That, okay, good call. I’m going to need to add snacks to my memorial tableau.

Louise: [00:23:02] Always add snacks.

Caitlin: [00:23:04] But this extreme embalming practice didn’t start in New Orleans. It was Puerto Rico.

Louise: [00:23:10] Right! It actually gained popularity in San Juan, Puerto Rico back in 2008 when Angel Luis Pantojas’ family chose to have Marín Funeral Home stage his body standing up in their living room.

Caitlin: [00:23:23] How do you be the originator of that practice? How do you go from just every normal funeral having the body lying down to, “You know what? My child will be standing up.”

Louise: [00:23:32] Well, it was actually what Pantojas wanted. He saw his father’s body in the casket, and he was like, “Nope, NOT FOR ME. I don’t want that.” So when he died, his family honored his wishes.

Caitlin: [00:23:45] See people? This is why talking about your death plan is so important! You could be a revolutionary.

Louise: [00:23:50] So when he died, folks came from far and wide to see what was dubbed “el muerto parao” or “the dead man standing”. And after that—and after some government inquiries about the legality of the practice, as well as some concerns in the Puerto Rican funeral industry about lavish funeral stagings becoming a competition in the underworld—

Caitlin: [00:24:11] —“underworld” like crime and gangs, right? Not underworld like Hades.

Louise: [00:24:17] Correct. But after all that muerto parado services—or standing dead services—were embraced. There was a taxi driver was positioned driving his beloved cab; and there was another man who loved the superhero The Green Lantern so much that he was elaborately posed as him.

Caitlin: [00:24:37] So ultimately they determined these services are legal.

Louise: [00:24:40] They are. In 2012 a law passed in Puerto Rico recognizing muerto parado services as legal. As long as they’re not placing the corpses in “immoral” poses.

[00:24:54] So I guess I can’t die in Puerto Rico.

Caitlin: [00:24:55] I wonder what constitutes an “immoral pose”—

Louise: [00:25:03] Right?

Caitlin: [00:25:03] —at a funeral. It reminds me of the Body Worlds exhibition where they have the corpses posed having sex or spiking a volley ball.

[00:25:08] I have thought a lot about what is so appealing about these funeral stagings.

Louise: [00:25:12] Yeah, I mean… You know, I think it has a lot to do with feeling like the dead are happy or at peace. I mean, remember Maw Maw Burbank? Well, amidst all the music and dancing at Burbank’s funeral her family said it was like she wasn’t gone, and the staging captured who she was.

Caitlin: [00:25:29] Busch beer and cigarettes, and the whole thing.

Louise: [00:25:33] Right, I don’t know. It may not be how you or I envision engaging with a dead family member, but for some people I think it’s a way to be less intimidated by death.

Caitlin: [00:25:44] I’d do it to my mom. Sign me up. I agree with you. I, for a long time, have been against embalming as a routine as a routine practice, so, a “no matter what practice,” because in so many cases it’s just not necessary for a family. But if you’re going to go all out like this and you’re posing the body. It’s a boxer, it’s sitting on a motorcycle, you need embalming to accomplish that. And families are totally aware of the wildness they’re getting into when they’re signing up for this type of viewing.

Louise: [00:26:15] You know, some people might say that it’s a form of death denial, but I don’t think so. These families make no mistake that their loved ones are dead. Sure, it’s not the same as a home funeral, but I’d bet there’s some heavy death-related mental processing going on when you have to decide what your mother’s corpse is going to be drinking, or smoking, or watching on TV.

Caitlin: [00:26:36] It’s super interactive and the family’s collaborating. And embalming is seen as something that happens in secret, behind the scenes, but this makes it public and so dynamic.

Louise: [00:26:49] I don’t think I’ll ever be “pro-embalming,” personally, but if you’re going to embalm, I think this is a great way to do it. I see a lot of positives.

Caitlin: [00:26:57] Plus, a tableaux like this is so far beyond good taste, or at least what we think of as good taste, that it transcends itself and comes back around and is very cool somehow. Like ‘70s décor. I’m proud of them, honestly. Good for them, for making that decision.

[00:27:13] [Music plays.]

Caitlin: [00:27:26] Death in Afternoon was written by myself, Louise, and Sarah, with additional writing by Allison Meier. Engineering by Paul Tavener at Big City Recording Studios. Editing and original music by Dory Bavarsky. We’ll see you next week deathlings.