Go behind the scenes of this article as we talk with the doula and the lawyer taking on California’s Funeral and Cemetery Bureau on our podcast Death in the Afternoon.

Defending Your Right to a Good Death

Death doulas and end-of-life guides have been providing valuable non-medical, culturally competent support and information to dying people and their communities for centuries. But what would happen if the right to share critical information about your rights in death, and how to care for your dead were taken away?

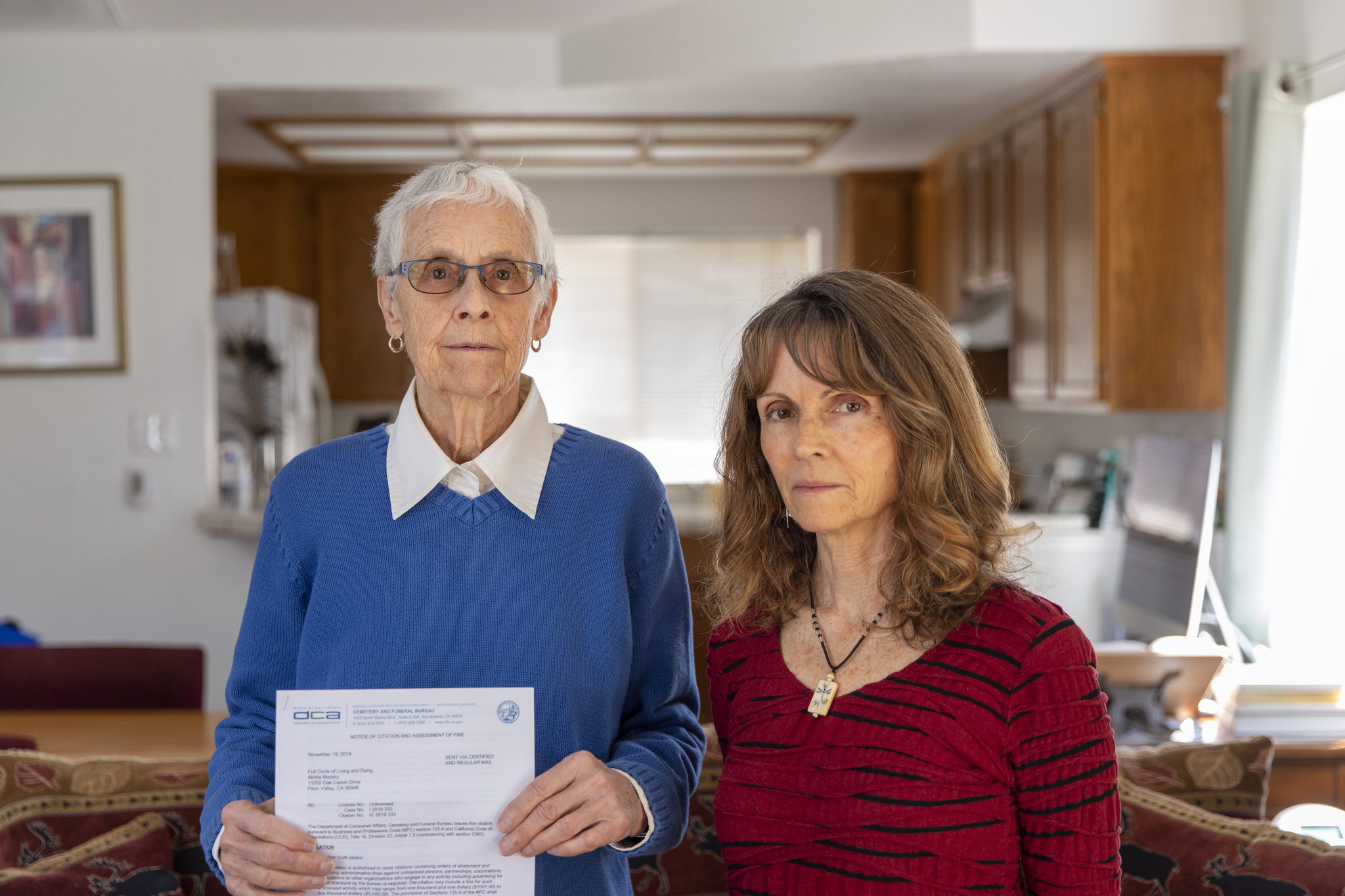

Akhila Murphy is an end-of-life doula and the founding director of Full Circle of Living and Dying; she does the critical work of providing non-medical support to people through their end-of-life and dying experiences and education about these all too often fraught and complicated subjects. Murphy’s work is as holistic as it is skilled; she is part of a community of death doulas across the country and the world that practice this centuries old tradition. But she, and her organization are also at the center of a lawsuit where funeral home directors in her home state of California are doing everything in their power to stop her, and others like her, from providing important information and support regarding end-of-life care and choices.

Image via the Institute for Justice.

Donna Peizer and Akhila Murphy of Full Circle.

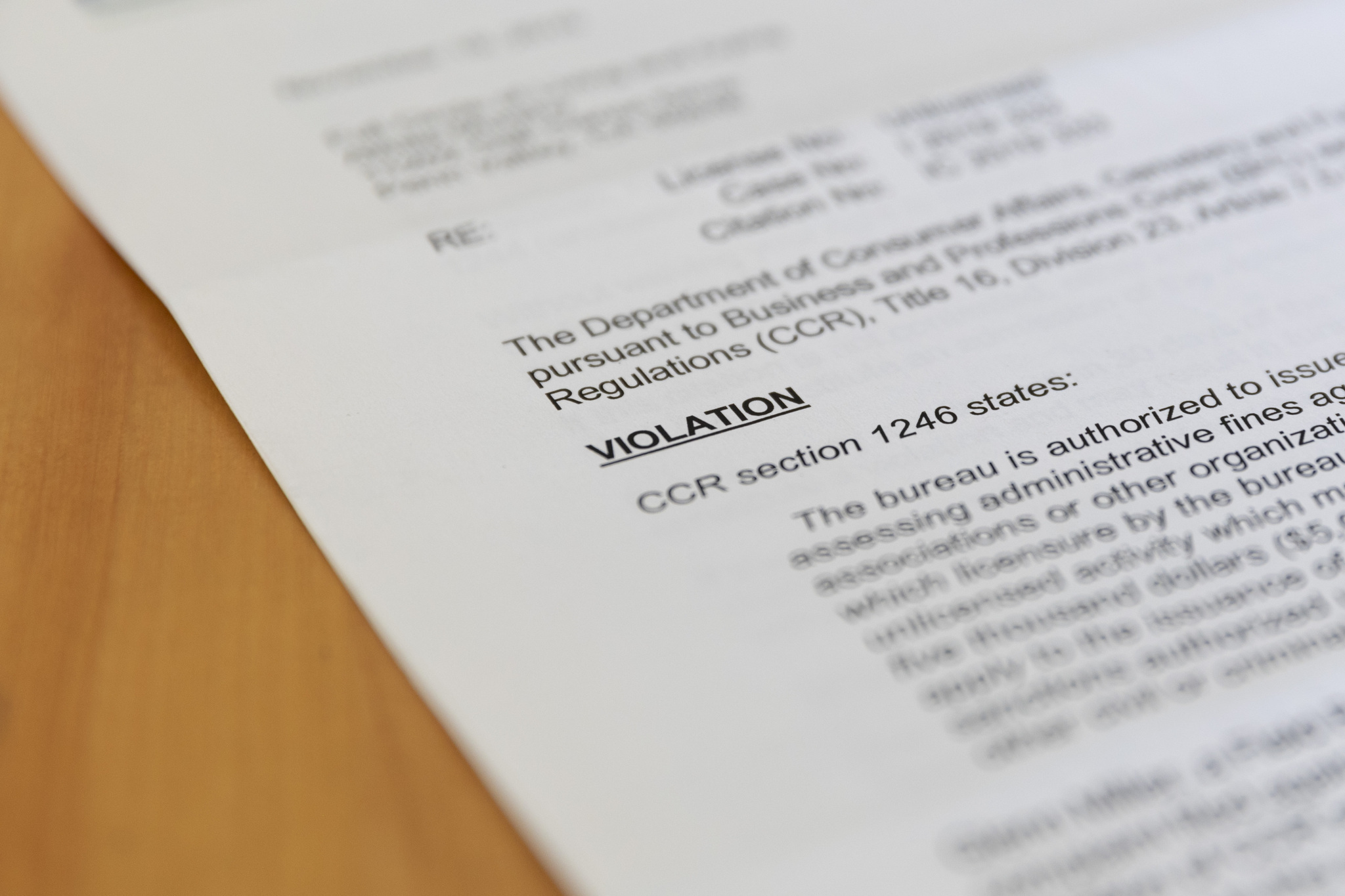

In 2019, the California Cemetery and Funeral Bureau issued an order to Full Circle instructing them to stop “advertising” as a funeral agency, until they were fully licensed. The problem with this order? Full Circle is not a funeral agency, and even contains a disclaimer on their website that clearly states that they are not a funeral home and do not offer funeral services.

In June of 2020, Full Circle filed suit against the Bureau claiming that their order violated their First Amendment Rights; doula work largely involves educating people on their options and resources – by restricting this action the lawsuit alleges they are infringing on their rights to free speech.

Becoming a licensed funeral agency in the state of California would mean that Full Circle would have to abide by certain procedures and requirements like having a space to store and embalm bodies; they would also have to pass a number of exams on information specific to funerary practices and embalming that may be irrelevant to the care work doulas do. But the implications of this case extend beyond logistical formalities.

“If subjected to the same regulations as conventional funeral directors, many death doulas will be priced out of business and forced to stop offering these invaluable services altogether.”

“Ultimately, this case is about whether or not death doulas will be able to continue to offer their services in California,” says Jess Pezley, a staff attorney with Compassion and Choices which filed an amicus brief in support of Full Circle in the case. “If subjected to the same regulations as conventional funeral directors, many death doulas will be priced out of business and forced to stop offering these invaluable services altogether.”

Image via the Institute for Justice.

Doula work is a centuries old practice; you might be familiar with birth or abortion doulas who provide support in a similar dynamic to pregnant patients around the world. Like reproductive health doulas, end-of-life guides and death doulas ensure that the support people receive at these critical moments in their lives is culturally competent – appreciative of the many spiritual and cultural beliefs and experiences that shape our relationships with death. This doula work also involves bridging the gap between modern funerary care and the more ancient practices surrounding death care; a connection that is especially pertinent for marginalized communities, who, like in birth, pregnancy, and abortion care, are often given the least access to autonomy. In fact, end-of-life doulas often do the radical work of ensuring that cultural death practices live on – which makes the attacks on this work even more troubling; without end-of-life guides and death doulas, many marginalized communities may experience yet another barrier to accessing what they consider a “good death.”

The distinctions between the services provided by funeral homes and the services provided by end-of-life doulas like Murphy are vast; while funeral homes need to be licensed and abide by certain regulations to protect consumer health and safety, there is no such need for the work doulas do. Unlike funeral homes, end-of-life doulas are not necessarily in possession of a body; many death doulas are, but others are not. Commonly, they share information with a dying individual and their loved ones about their options and help to best facilitate their wishes. “It is critical for people to know their options in order to make informed choices that feel proper for their individual dying person,” says Murphy. “End-of-life doulas often act as a liaison between mortuary care and cemetery districts. We inform clients that embalming is not required by law in any state with the exception of special cases.”

Murphy’s work can involve everything from supporting people through the process of arranging a funeral with a modern funeral home, to educating them on the best practices for a home funeral – something many folks might not even realize is an option available to them. “Different people have different preferences and wishes for when they pass away,” she says. “And for hundreds of years some people have preferred in–home funerals. In order to perform those in-home funerals, doulas are essential. People welcome doulas into their inner circle and we provide much-needed support during these times.”

In the simplest terms, Murphy’s work is mostly “pure speech,” says attorney Ben Field at the Institute for Justice, the organization representing Full Circle of Living and Dying.

With the distinctions so obvious, it might be hard to imagine why the Bureau might be motivated to try and stop folks like Murphy from doing their work.

Lee Webster is a funeral reform advocate, and the Executive Director for Funeral Resources, Education & Advocacy in New Hampshire; she paints a somewhat David and Goliath-like picture of the dynamic between doulas and modern death practitioners like the Bureau. “The current movement to take back the practice of caring for our own dead is significant not just because it necessitates going up against a $22B monolithic industry,” she says, “but because it necessitates fighting hard to keep those rights that are threatened by an industry that appears to want to limit our personal freedoms.

This is not about wanting to bring back the old days; it’s about preserving our rights in the future to choose how to care for our own dead.”

“This is not about wanting to bring back the old days; it’s about preserving our rights in the future to choose how to care for our own dead.” – Lee Webster

Webster sees the matter at hand as a straightforward one about privacy and autonomy; seeking the services of an end-of-life doula is no different than choosing to see a homeopathic doctor, or obtaining culturally significant treatments such as traditional Chinese medicine.

“The State does not have the right to tell us what to do in the privacy of our own homes and lives,” she says. “It can not tell us who to marry, what schools to send our kids to, or whether to bury or cremate.”

Field says that if the Bureau is allowed to prevail here, it will have devastating impacts on the autonomy of people in their ability to control their end-of-life plans.

“If the California Cemetery and Funeral Bureau is allowed to require a license to offer end-of-life advice, it will dramatically narrow the information available to individuals and families making some of the most intimate and important choices they will ever face,” he says. ”Rather than serving California consumers and families, it would entrench the conventional funeral industry against alternative choices that people want to explore for themselves and their loved ones.”

End of life doulas essentially are in the business of sharing information and that scares funeral home directors who rely on the myth that families need their services – their pricey services – to care for their loved ones. They worry that if people are fully apprised of all the different ways someone can die, that it will render their services at least partially obsolete. But if funeral home directors are threatened by the mere availability of information, doulas like Murphy are not to blame – their own reticence to meet the needs of the people they serve, is.

Death, like life, should be an autonomous experience, left untarnished by our inability to meet financial constraints or other onerous and frivolous impositions. End-of-life doulas can help bring us one step closer to that reality.

“Traditional funeral homes may feel threatened by this competition,” says Murphy. “But at the end of the day, we’re simply providing families with a service they want.”