“Avoid idleness and intemperance,” this motto that was carved at the front of the building encapsulates the predominant Victorian views of the workhouse, an institution that provided housing in exchange for work. The people who ended up here were seen as lazy, overindulgent, and unwilling to prosper in life. These people weren’t just poor, they were the undeserving poor. It’s a discourse still strikingly familiar, reminiscent of current debates about benefit claimants.

Destitute and Dissected: The Dead From a London Workhouse

On the same street in London where Charles Dickens lived twice during his formative years stands the Cleveland Street Workhouse, a severe brick building built in the late 18th century that is now part of Middlesex Hospital. Archaeologists involved in its renovations are studying the burial site associated with it, and gaining evidence on how the original workhouse operated and on the living conditions of its inhabitants. But this painstaking work is also revealing that the remains of the destitute poor were regularly dissected for anatomical purposes against their own wishes.

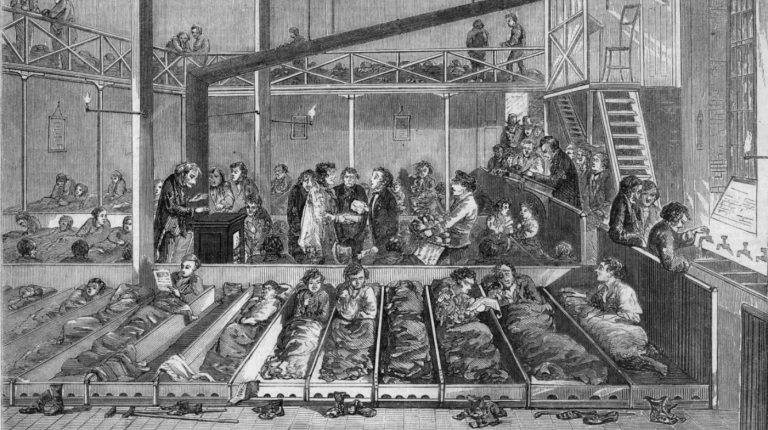

Mansell/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

Workhouse shelter, in 19th century London

Our modern ideas about the workhouse come in large part from Victorian popular fiction, notably from the works of Charles Dickens, who lived near the Cleveland Street Workhouse—then known as the Covent Garden Workhouse—in his formative years, and might have taken inspiration from it. In Oliver Twist (first published between 1837 and 1839) he exposed the brutality of the system through the fictional story of a child born and raised in the workhouse—it was the author’s response to the New Poor Law of 1834, which established the system.

The 18th and 19th century Poor Laws were intended to tackle the ever growing population of the elderly, sick, and poor. The previous system of poorhouses and almshouses was thus replaced by the workhouse system, which implied full-time forced labour. The severe façade of the Cleveland Street Workhouse is a testament to the principles behind its conception: workhouses were designed to be unappealing and forbidding. A deterrent, not an invitation. The last resort, the place only someone desperate would consent to be taken. This cruel logic allowed the government to reduce expenditure on poverty.

For the Victorian working classes, there was nothing more horrific than ending up at the workhouse. Journalist Henry Morton Stanley, who famously tracked down the missing explorer Dr Livingstone, described the workhouse where he grew up as a “house of torture”. Many surviving historical documents provide a harrowing read. Letters from workhouse inmates remark on the conditions they endured, with children being violently punished and adults—including the elderly and the infirm—regularly abused. The regime was “worse than a prison”, “inhumane”, “brutal”. Every aspect of the existence of the inmates would be regulated: from the clothes they wore to what they ate. Separated from their families, stripped off their belongings, having reached rock bottom, with no possibility to rise, the workhouse poor were treated punitively, as if they were part of an inferior class whose life situation was entirely of their own making. The archaeological study of workhouse burial grounds proves that the social division between the poor and the workhouse poor persisted after death.

Cleveland Street Workhouse

The burial ground associated with the Cleveland Street workhouse was active between 1790 and 1853. The current excavation, carried out by archaeologists from Iceni Projects and L-P Archaeology, reveals it was divided into two areas. The southern part appears to contain the remains of the poor people from the parish, with evidence of dental diseases, nutritional deficiencies and chronic infections. Historical documents show it was conceived as an “overspill” cemetery for the parish of Covent Garden. The burials in the northern side, however, while showing similar health patterns, paint a different picture: this section seems to be the area reserved for those who died in the workhouse—the destitute poor.

“The remains found in this area are noticeably different,” says Claire Cogar, director of Archaeology at Iceni and head of the excavation. “They don’t follow the typical orientation seen in the southern part of the cemetery, which was north-east south-west. Burial plots are arranged even more densely, forming up to ten burials in one grave, sometimes with more than one person in the same coffin.” But perhaps the most harrowing of all is the extensive evidence of post mortem dissections. Skulls, limbs, and body parts were cut open. One of the skeletons presented remains of a pinkish white substance, revealed to be a mixture of lead carbonate, pigments, and coniferous resin. This substance would have been injected into the circulatory system to better visualise the blood vessels during a demonstration dissection, before the remains were interred in the workhouse burial ground.

If with the Poor Laws parishes could take the destitute off the streets and profit from their labour, with the Anatomy Act of 1832 they could also legally profit from their deaths even against their will. The legal supply of bodies to the medical schools in London rose, reducing and eventually ending the illegal practices of the resurrectionists, but the new law introduced a new anxiety among the Victorian poor: “the existential foreboding triggered by the prospect of post-mortem dissection”, in the words of Sambudha Sen. The fear of dissection had started in the 18th century, when changes in British medicine highlighted the importance of gaining practical experience in the dissecting room. The demand for corpses caused the proliferation of grave-robbers and resurrectionists. The consequent anxieties resulted in the use of mausoleums and mortsafes by the well-off, while the poor had relations or friends keep an armed watch at night. However, the Anatomy Act of 1832 made it legal to dissect the workhouse poor, even when they opposed to it.

These people were—unwillingly—part of an industry; their bodies were used as a commodity in public autopsies for anatomy students and for the advancement of modern medicine.

Judy Wilson

Mortsafes in a churchyard, placed over graves to deter bodysnatchers.

Unclaimed bodies are still used for anatomical purposes in some parts of the world. In a 2014 article for The New Scientist, David Gareth Jones stated they still constitute the source of cadavers in around 20% of medical schools in the US and Canada. In some US states, unclaimed bodies are passed to state anatomy boards.

The Cleveland Street Workhouse burial site is a striking memento of how society is built on the backs of the oppressed—on the one hand, deformities, stunted growth and work injuries hint at the terrible work conditions they endured; on the other, the evidence of dissections after death reminds us of their lack of autonomy and choice. The archaeological study of burial grounds tells us that not even death, the ultimate frontier, can obliterate social divisions. It is a sobering experience, and one that reminds us that social activism should also be concerned with our deaths.

Maria J. Pérez Cuervo is a freelance writer, editor, and communications manager based in Bristol, UK. Her work has appeared in Fortean Times, Mental Floss, Daily Grail, The Order of the Good Death, and many other places. She’s the editor of Hellebore, a magazine devoted to British folk horror and the occult.