Jenn Park-Mustacchio is a funeral director and embalmer, horror movie nerd, and married mother of two in Haddon Township, New Jersey. She studied anthropology and human biology at the University of Pennsylvania, and has been in the funeral industry for 14 years — since she was 18. Here, she recounts her first Buddhist funeral.

*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*

It was a dark and blustery evening and, as the most recent funeral home licensee, I was saddled with the task of a 3 am embalming.

I clumsily fumbled for the key to the back entrance of the funeral home. Blindly searching for the light switch inside, I became aware of a low whisper. Upon flipping the switch, I realized the noise was coming from the occupied stretcher. Frightened, yet intrigued, I unzipped the bag on the stretcher and found a tape recorder playing a chant. Relief swept over me; everything was as it should be.

Upon further inspection, I noticed a bowl of rice with a hard boiled egg (placed at the head of the deceased) and a machete with plantains (placed upon the chest). There was also a note from the director, who did the removal, instructing me to leave the tape recorder on play and to place the food items back in their appropriate positions after embalming.

Upon further inspection, I noticed a bowl of rice with a hard boiled egg (placed at the head of the deceased) and a machete with plantains (placed upon the chest). There was also a note from the director, who did the removal, instructing me to leave the tape recorder on play and to place the food items back in their appropriate positions after embalming.

I removed the deceased gentleman from the stretcher and went about embalming, placing the items back in their assigned positions once the process was complete.

I returned to work sleepy-eyed the next morning and was told that funeral arrangements were to take place at 9 am and that I, as the novice director, would be assisting the senior director with arrangements. I quickly perked up at the thought of directing a funeral that I knew would be unlike any other I had worked on.

The doorbell rang promptly at 9 and the widow, the sister of the deceased, and an orange-clad monk followed us into the office to make arrangements. What proceeded was a very enriching lesson on Cambodian Buddhist death rituals.

The family explained that, ideally, a monk would be at the place of death to chant when the soul exits the body. Chanting calms the soul, which is in a state of confusion and fright after exiting the body. The food is there to nourish the soul, which is unaware that it has passed. The soul remains in transition for days, so the body must remain at rest in the funeral home for a number of days, and the soul of the deceased must be put at ease with food and chant throughout the difficult time of transition.

As per tradition, we kept the deceased for seven days. The food and recorder stayed there with him for the entire week before the funeral and, though it may have calmed the soul, it drove me a little crazy listening to that chant for seven days straight.

On the sixth day, we dressed the gentleman and were instructed to remove the buttons on his clothing (to make it easier for the soul to escape, if it hadn’t already). On the day of disposition, the sister of the deceased, his wife, and their 3-year-old son arrived clad in white, the traditional color of mourning in southeast Asian cultures. The little boy’s hair was freshly shorn, as per tradition. The widow and sister of the deceased left their hair intact.

On the sixth day, we dressed the gentleman and were instructed to remove the buttons on his clothing (to make it easier for the soul to escape, if it hadn’t already). On the day of disposition, the sister of the deceased, his wife, and their 3-year-old son arrived clad in white, the traditional color of mourning in southeast Asian cultures. The little boy’s hair was freshly shorn, as per tradition. The widow and sister of the deceased left their hair intact.

As the monks chanted and recited the sermon, they burned incense. I was told that wealthy Buddhists burn money, too — a tradition that struck me as similar to the Ancient Greek tradition of placing money on the eyes of the deceased in order to pay Charon to cross the River Styx into Hades.

After the funeral ceremony, we formed a procession to the crematory and I watched from the side view mirror of the hearse as mourners threw popcorn from the windows — a trail for the soul to follow.

At the crematory, the whole procession joined us inside and the wife of the deceased ignited the retort. Igniting the fire that would consume her husband’s human remains — the process that would allow his soul to leave the body and to go on to the afterlife and await reincarnation — was her final gift to him.

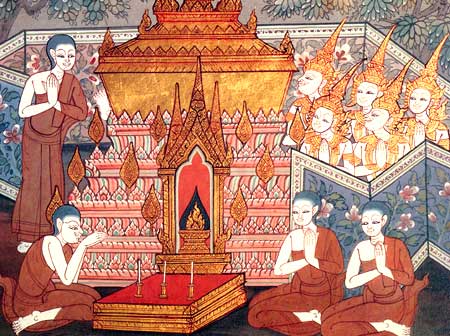

After the service, I joined the family back at the Buddhist temple for a meal of fish and a discussion of their culture (which included an explanation of how they fled Cambodia when Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge were killing their families). One of the mourners explained that once the cremated remains were returned to the family, they would be kept in a stupa, a dome-shaped structure that holds Buddhist relics, in the temple compound. There, she said, the deceased would be close to Buddha and to the monks who would help his soul be reborn sooner.

Bearing witness to the very personal journey of this family and their deceased loved one was truly an honor, and one of the most fulfilling experiences of my career. I was so pleased to be welcomed so warmly by the family and to learn firsthand about a culture with which I previously had very little familiarity. The family was thrilled with my willingness to learn, and the monks even asked me to explain the principle of Christ in Western culture. I admired the family’s peaceful nature in the face of great hardship — it was their faith that had provided them with strength when faced with the horrors of genocide, and it helped them now through the loss of their loved one.

***