Like the man-eating nekomata, the monsters of the Kamakura period (1185–1333) were on the scary side. This is partly due to an apocalyptic belief in mappō, a Buddhism term meaning “the latter of the days of law.” Like some Christians today, Kamakura-period Buddhists believed they were living in End Times. The world would soon be over.

People believed that the cycle of reincarnation had reached its end, and there would be no more chances, no more lifetimes to redeem lost souls. Anyone still alive was stuck between damnation and redemption. It was your last opportunity to plead to the Amida Buddha for mercy, and hope he would grant you a spot in the heavenly garden known as the Jōdo Pure Lands. If not…the oni were waiting to flay your skin from your bones for all eternity.

This fear lead to a form of art called jigoku-zōshi, meaning “hell scrolls.” These depicted the painful suffering awaiting those who didn’t hurry up and get saved. Like medieval Christian art depicting Satan and damnation, hell scrolls were designed to terrify an illiterate population into following the righteous path of the Buddha.

Most of these paintings depicted oni tearing people apart and feasting on their body parts. Sometimes oni carried these poor bodies in flaming carts. The belief eventually developed that oni crawled the Earth looking for sinners and piled them into flaming carts to drag before the dread judge of hell, Emma-O.

As with much Japanese folklore, the image of the flaming cart went dormant with the end of the Kamakura period. The people of the time were right about one thing—their world did end in a way. About a century following the end of the Kamakura period, the political structure of Japan collapsed. Numerous samurai lords called daimyo each decided they should be the sole ruler of the country. This led to a massive period of civil war known as the Sengoku Jidai, or the Warring States Period (1467–1603). Most of Japan was too busy killing and dying to fret about yōkai. The monsters disappeared until Tokugawa Ieyasu came out as the winner of the civil wars and began the 260 peaceful years of the Edo period.

The flaming cart, now called kasha or hi no kuruma, was reawakened during the Edo period. Removed from its oni companions, the flaming cart began to appear descending from the sky, accompanied by thunder and great winds. Superstition said that when thunder was heard during a funeral procession, it meant the kasha was coming.

What exactly this flaming cart was coming for, and who exactly was riding it, wasn’t clear at first. In the 1687 book Kii-zodanshu (奇異雑談集; A collection of the idle chat of mysterious things) there is a story called “The thing that came from the storm clouds to steal a corpse in the manor house near the rice fields of Echigo.” During a funeral procession, there was a loud clap of thunder and a beast riding a flaming cart came down from the sky to snatch the dead body. An illustrator depicted the kasha as being ridden by Raijin, the Shinto deity of thunder and lightning. This association made sense if you think about the carts’ association with thunder.

All of the appearances of this kasha were heavily influenced by Buddhism. A custom arose of priests placing rosaries around the necks of the dead bodies to protect them from kasha. Stones were placed on coffin lids to keep the corpses from rising up to ride in the fiery vehicle. Although that was no guarantee.

All of the appearances of this kasha were heavily influenced by Buddhism. A custom arose of priests placing rosaries around the necks of the dead bodies to protect them from kasha. Stones were placed on coffin lids to keep the corpses from rising up to ride in the fiery vehicle. Although that was no guarantee.

So how did this flaming cart from the sky become a cat?

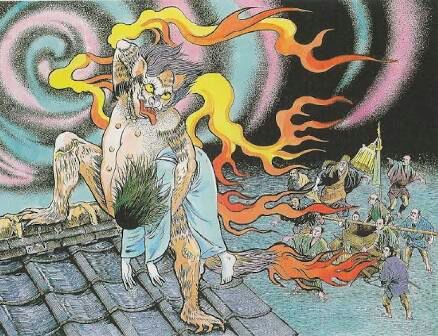

As with many yōkai, the origin of the cat-like form of kasha comes from artist Toriyama Sekien. When Sekien drew a kasha for the second volume of his Gazu hyakki yagyō (画図百鬼夜行; The Illustrated Night Parade of a Hundred Demons) in 1776, he drew a bizarre cat-demon covered in flames. Sekien often blended his own imagination in with folklore. He felt no shame in simply inventing things. For his illustrations in later volumes, he would write notes or stories discussing the creature in question, but for these earlier depictions he left only the picture and the name. We have no idea why he chose to make the kasha a cat.

Sekien’s influence on yōkai was so profound that people accepted the cat-like kasha and the stories began to follow. In Boso manroku (茅窓漫録; Random talk of outside cogon grass; 1833) a story was told of a funeral procession interrupted by a mighty wind and thunder that swept away the coffin as a kasha came down to retrieve the corpse. This kasha was not the flaming cart however, and was identified as a mōryō, a flesh-eating animal spirit, and was drawn resembling a cat.

In another book, Hokuetsu seppu (北越雪譜; Snow Country Tales; 1837), a story is told–said to come from the Tensho era (1573–1592)–where a funeral is interrupted by a gust of wind and a fireball that comes from the sky. Inside the fireball is a massive split-tailed cat (the calling card of the nekomata) that snatches up the coffin. But the priest attending the funeral beats away the kasha with his staff.

Over time, this cat-form of kasha began to dominate. Like the nekomata and the bakeneko, kasha were said to be transformed house pets that lived an unusual span. Others said it was the presence of corpses that caused the transformation. A cat left alone too long with an unattended corpse would transform into a kasha and drag the body away. Fear of kasha became so great that when someone died the household cats were instantly banished, and coffins were even weighed down with rocks to prevent them from being dragged away.

As the kasha became more catlike, its influence spread to other kaibyō. Powers and stories were mixed and matched. Specifically, kasha and nekomata became blended. Nekomata inherited traces of the kasha’s appearance and necromantic powers. Some stories of nekomata show them with twin fireballs hovering over their split tails, a leftover from the kasha’s flaming halo. Both kasha and nekomata were also said to be able to wake the dead. They could leap over coffins, weaving invisible strings and thus able to manipulate bodies like corpse puppeteers. Other rumors spread, but one thing was sure; when a person died, you had better kick the cat out of the room.

The association with cats and corpses seems grim, but it is not entirely without logic. Cats eating their dead owners is a real thing. Although it is rarely discussed, it is well-known amongst those who make the hauling of the dead their trade that if you die alone with cats in the house who are not being fed…well, cats do get hungry. The phenomenon is called postmortem predation. Dogs do it too, although they have more trepidations about feasting on their former masters and will wait a couple of weeks. Cats waste little time. After a day or two alone with a corpse, cats will start to chow down. If a person dies alone and the corpse is undiscovered for long enough, the family pet might make a nice little feast and leave little to be discovered.

Because of this, it doesn’t take too much imagination to see how the flaming cart that comes from the sky to snatch bodies became mixed with the very real situation of corpse-eating cats.

Zack Davisson is an award-winning translator, writer, and folklorist. He is the author of YUREI: THE JAPANESE GHOST, YOKAI STORIES, and THE SUPERNATURAL CATS OF JAPAN from Chin Music Press, and an essayist for WAYWARD from Image comics. He lectured on translation, manga, and folklore at Duke University, UCLA, University of Washington, Denison University, as well as contributed to exhibitions at the Wereldmuseum Rotterdam and Henry Art Museum. He has been featured on NPR, BBC, and The New York Times, and has written articles for Metropolis, The Comics Journal, and Weird Tales Magazine.

As a manga translator, Davisson was nominated for the 2014 Japanese-US Friendship Commission Translation Prize for his translation of the multiple Eisner Award winning SHOWA: A HISTORY OF JAPAN. For Drawn & Quarterly, Davisson translates and curates the famous folklore comic KITARO. Other acclaimed translations include Satoshi Kon’s OPUS and THE ART OF SATOSHI KON, Mamoru Oshii’s SERAPHIM: 266613336 WINGS, Kazuhiro Fujita’s THE GHOST AND THE LADY, Leiji Matsumoto’s QUEEN EMERALDAS and CAPTAIN HARLOCK DIMENSIONAL VOYAGE, Go Nagai’s CUTIE HONEY A GO GO! and DEVILMAN: GRIMOIRE, and Gainax’s PANTY AND STOCKING + GARTERBELT.