For the last eight years of my brother Chris Reimer’s life, I lived in an urban coastal city. I was trying to become a writer. He lived in the backwater prairie city of our birth, where he was trying to become a musician. In those days we connected in person on the Christmases I could afford to come home, or during brief visits when he came through town on tour. Otherwise, our relationship occurred over email and text. I’d mail books I thought he’d like, and he’d share music files.

He died ten years ago, February 2012, the day before my 32nd birthday. He was 26.

In the decade since, our relationship has become one of excavation and posthumous collaboration. Grief turns us all into vultures. We sift our loved ones’ affects selfishly. We’re looking for something to hold, something to keep, some new facet of their personality that we never got to know. A new story, or a message from the grave. Over a ten year period, in fits and starts, I took what I could find, what I knew of my brother, and the love that needed an outlet, and turned it into an art project called GRIEFWAVE. GRIEFWAVE includes 40 webpages of art, photography, sound mixes and video that collages my own poetry and audio texts with my brother’s music and art.

In sifting through the scribbled notes and journals Chris left, I found the sense of humour and the harsh self-criticism that I knew as him, but I also found things that surprised me. I don’t know if he thought of himself as a writer, but his journals held poems and sketches of short stories. His writing was good—better than mine. His voice was freer, less self-conscious. His images were more original. There’s no sibling rivalry after death. I felt only pride.

I always knew we viewed the world from a similar lens, but reading his journals was uncannily like reading my own. We wrote in the same voice. Same phrasing, patterns, and fears. Our brains turned out to be so similar I’d soothe myself by fantasizing that we were improbable twins, although I was six years his senior. I had to find ways to reckon with the absence of the baby brother who made more sense to me than anyone else I knew.

We were smart but caustic. I did better in grade school and he was more athletic and musical. But we could never start things and never finish them. Authority made us bristle and snarl. Bursts of manic creative activity alternated with days of sluggishness that I now recognize as low dopamine. In our adolescence we’d spend weekend days together on adjacent couches, numbing out to MuchMusic, Canada’s answer to MTV. We had emotional meltdowns when our creative output couldn’t match our vision. The word FAILURE appeared in all caps in both our notebooks. People admired our creative talent, but we were hobbled by shame.

In 2015, three years after Chris died, his partner was diagnosed with ADHD, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Like me, she is smart, sensitive, independent, able to do a million things at once or nothing at all. Like me, she is listening to you but scanning the room because her brain is taking in everything at once. Shit, I thought, if she has it, I must have it too?

And Chris as well?

In so many ways, Chris and I were the same. We struggled with self worth. We couldn’t buckle down to focus on our passions, we’d beat ourselves up for that struggle. What might appear as laziness or reticence to outsiders was, I now think, the challenge with executive function that is the hallmark of ADHD. The inability to start a project if we knew it couldn’t be perfect. We suffered with rejection sensitive dysphoria; we wanted to belong, but felt different, apart from others.

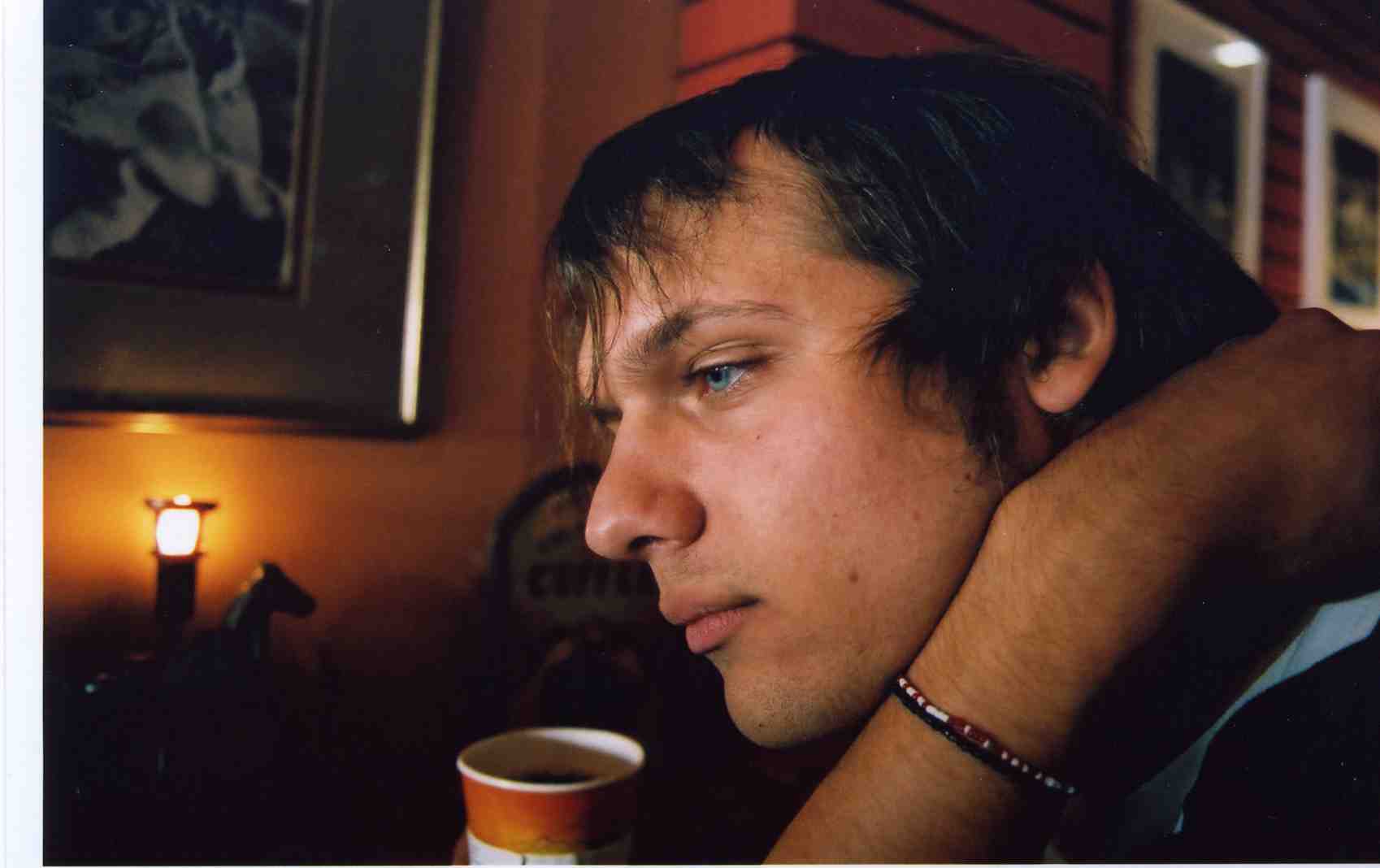

What’s often hardest to bear when people die young is that they never get the chance to fully form. In the last year of his life, Chris was shaking off some of his early low self-esteem. He was turning into a man, still gentle and kind, but more confident.

It pains me that I’ve had the opportunity to learn about my diagnosis, while he never had that chance. I’ve befriended other late-life diagnosed adults, benefitted from coaching, and learned tools and skills that work for those of us for whom “make a list” might as well be “drive to Mars.” I wish he’d been able to do the same. My relationship to Chris, to my grief, and to the posthumous collaborative project GRIEFWAVE evolved steadily over the ten-year period of making it: the lost 32-year-old who recorded the sounds her boots made in the Old Banff Cemetery’s snowy graves was not the wiser 42-year-old using spreadsheets, LucidCharts, and Adobe software to put a multimedia project together. I still used the poetic fragments he’d written, still channeled my grief into something new, but I’d gained perspective. I had compassion for my early, broken self, and I had compassion for the ways Chris and I both struggled to make sense of ourselves in our teen and early adult years.

What remained unchanged was the absence of my favourite human, and the ways I used artmaking to return to him, our shared sibling conversations, and the creative interplay of our self-effacing, neurodivergent brains. Adding his poems in with my photoshop collages, or his music with my poetry felt like a way to keep talking. The project I put out into the world was a love letter and an “I see you, brother. I’m still listening.”