My uncle Alex was a man that taught me that in the hardest of situations, a solution could always be found. He was the glue that held together my dysfuctionally-functional family and served as my own, personal voice of reason. That voice has now been silenced. It wasn’t supposed to be like this.

Prior to my acceptance into the Mortuary Science program at Cypress College, my uncle started getting sick. According to the doctors it seemed his symptoms were that of a stroke. As the time went by, my uncle started to make fewer appearances at family gatherings. The next time I saw him, his movements were physically slower. He would speak fine, but his mouth looked out of sync when he would talk. His steps were slower, and his legs would quiver at random times. The following year, my uncle was noticeably thin and needed an aide to walk. He would ask about how my education was going and tell me what a “chingon” (ass kicker) I was when I brought home an A for an English Literature class centered around The Prince by Niccolo Machiavelli. It was this book that he gave to me in 7th grade.

Prior to my acceptance into the Mortuary Science program at Cypress College, my uncle started getting sick. According to the doctors it seemed his symptoms were that of a stroke. As the time went by, my uncle started to make fewer appearances at family gatherings. The next time I saw him, his movements were physically slower. He would speak fine, but his mouth looked out of sync when he would talk. His steps were slower, and his legs would quiver at random times. The following year, my uncle was noticeably thin and needed an aide to walk. He would ask about how my education was going and tell me what a “chingon” (ass kicker) I was when I brought home an A for an English Literature class centered around The Prince by Niccolo Machiavelli. It was this book that he gave to me in 7th grade.

That summer we learned my uncle had been suffering from ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s Disease, or its medical name Amyotropic Lateral Sclerosis. There is no cure.

Eventually, he became depressed and had tantrums, and regressed to childlike behavior as he struggled to understand what was happening to him. I was told it was unbearable to watch.

In December I was accepted into the Mortuary Science department of Cypress College. I was finally going to be going to school majoring for a career I have spoken about since childhood. The first person I called was my uncle. Sobbing, he said, “I am so proud of you. You’re gonna make me so proud.”

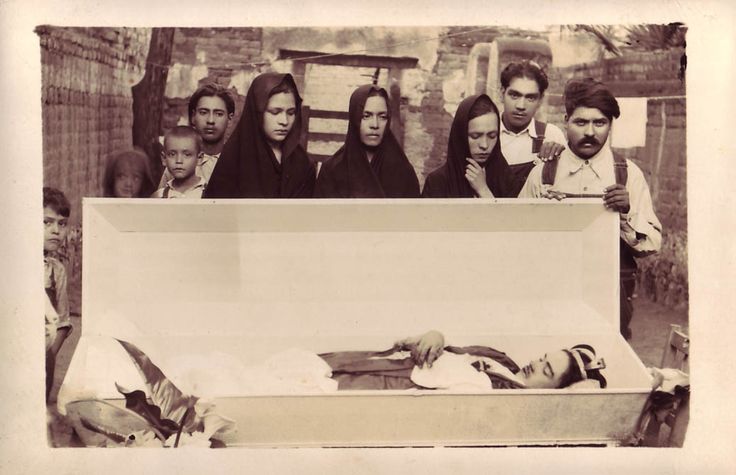

During one of our visits, I told my uncle about funeral customs in the Victorian Era and how before funeral homes existed, families of the deceased would care for them at home. I also shared that California was a “Home Death Care” state, meaning that legally the involvement of a funeral home was not necessary.

In turn, he shared with me the traditions of his family in Mexico, which are still practiced.

One day I stayed with my uncle while the rest of the family went out to run errands. He was now wheelchair bound and his speech slurred a bit more, but he tried hard to speak clearly, “Mijo, this disease is going to kill me. I’m scared for what is going to happen to the family when I am gone. I need you to promise me a few things.” I looked at him listening intently. “I don’t want to be buried. I want to be cremated. But I know that there will be issues no matter what happens. I trust you to take care of this. Remember how you told me about the home funerals? I want that. I don’t want any stranger to have me knowing that I have someone to take care of me. When the time comes, I know you’ll know what to do.”

On the morning of May 1st, 2015, I had a sense that something was wrong. During lab, I got a call from my mother confirming my fears. “Herman, baby, I’m sorry to call you while you’re at school. Mijo…your uncle died not too long ago. We don’t know what to do. We need you. Please call me as soon as you can.”

Although I had previously done many services for families at work, and helped dress, casket, and cosmetize human remains, there is really no way experience or funeral service education can prepare you for when a death occurs in your family.

As I approached the house, some family members looked at me. A woman on her knees who had been crying got up, crying out, “Don’t take him from me!” It was clear that some were under the impression I was coming to take my uncle away and they would no longer be able to see him. I spoke with the social workers from the hospice agency and told them what was to be done. I worked my rounds to see who was there, and ultimately the condition of my uncle’s body.

My uncle was in his room on his bed. The family was praying over him. After half an hour, I entered the room, not knowing what to expect. I hoped that decomposition would be delayed as long as it could. I had done extensive research on home death care, but I wasn’t prepared with all the necessary tools such as dry ice to inhibit decomposition.

I saw my uncle’s body lying lifeless on his bed as if he was tucked in to sleep. As corny as it sounds, he looked truly at peace, a small grin showed on his face. “You motherfucker. You weren’t supposed to die before me…who is going to keep this family in line now that you’re gone?” I whispered. As I touched his hand it was warm. I checked for post mortem issues but found none. I noticed he was dressed in his favorite soccer clothes. The hospice nurse and my aunt had shaved him, given him a sponge bath and dressed him. It is morbid to say this, but damn if my uncle wasn’t the best looking corpse I have ever laid eyes on.

That afternoon family members began to arrive. My uncle was the prime exhibition tonight, as a vigil was held over him. By evening, about 300 people were here. Some were paying their final respects to my uncle in his room, there was a priest in the backyard giving a sermon and afterwards, eulogies were said. I felt my uncle’s presence strongly. “This is what it is all about. This is how death should be celebrated,” I thought.

That afternoon family members began to arrive. My uncle was the prime exhibition tonight, as a vigil was held over him. By evening, about 300 people were here. Some were paying their final respects to my uncle in his room, there was a priest in the backyard giving a sermon and afterwards, eulogies were said. I felt my uncle’s presence strongly. “This is what it is all about. This is how death should be celebrated,” I thought.

Throughout the day, the one question I was repeatedly asked was, “Is this legal? Are we really allowed to do this here?” I was grateful to answer that question, rather than having to address the question I was dreading but ultimately, was never asked: “Why are we doing this?” It wasn’t a macabre thing in anyone’s mind to have my uncle here in his home.

As the night drew near I was asked to delay the funeral home from coming to pick up my uncle until the morning. “But only if it’s legal,” my family kept repeating. At midnight, I sat by my uncle’s side and I told him about the big turnout for his day. My uncle’s family never left his side as they retold stories and reminisced about his many quirks and lessons taught by him throughout the night. It was a “Good Death” if I ever saw one.

26 hours after the death of my uncle, I was carrying him across the hallway to be strapped onto a gurney where he would be taken to the funeral home that would process his cremation. Everyone agreed they were finally ready to say goodbye. And with that, my uncle was driven away as his last wishes were carried out, just as he had wanted them to be. Days later, his witness cremation would take place, and as my cousins and aunt said one last, private goodbye, I whispered that I was going to make him proud.

Tio, I hope you still are.

Herman Reyes is a licensed funeral director in the state of California. He currently shares his experiences as mortuary science school student on his blog, Adventures In Deathcare. You can also find Herman on the Adventures In Deathcare Facebook Page.