Writer & Order member Susie Kahlich is living and working in Paris. She is our guide to all things Parisian death.

*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*

Paris is a remarkable city: so beautiful, it really does look like a film set, and tourists, ex-pats and even, sometimes, Parisians wander around, oohing and aahing over the breathtaking beauty of the French capital, jamming up the sidewalks to snap photos of absolutely everything. They press against Haussmannian walls to get a fresh angle on the Eiffel Tower, pose next to beautifully aged entrances to Belle Epoque hotels, smile under the iconic blue street signs fixed to the sides of buildings. But what they never see are the plaques and engravings often hovering just above them, usually just out of their camera’s frame, right next to whatever typically Parisian thing they’re taking a photo of, completely unawares that they are missing the other typically Parisian thing: the dead.

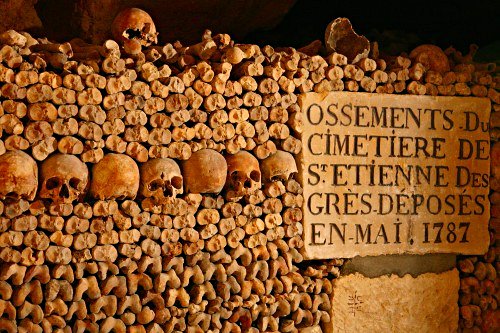

Paris is a city of death. A lot of people have died here, often in large groups, and often in bloody and violent ways. Death is memorialized all over the place. Public buildings often have signs marking the point from which entire neighborhoods were shipped off to death camps. Placards are affixed to the sides of cafés acknowledging political assassinations (my fave: Jean Jaurés, who was not assassinated anywhere near the avenue that actually bears his name). Cemeteries are squeezed in among the living, catacombs are stacked with skulls and bones, various kings, cardinals, queens and heroes are buried just beneath the stones of any of the city’s cathedrals that dot the city, while children, puppies and couples in love regularly skip through the sunshine across the bloody, bloody Place de la Bastille. Viva la morte!

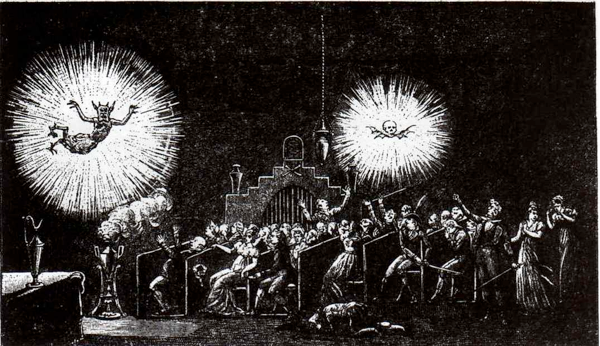

Speaking of the Revolution (weren’t we?), the magic lantern reached the height of its popularity in post-Revolutionary Paris, where Étienne-Gaspard Robert set up the first “fantasmagorie,” a magic lantern show in an abandoned crypt of a Capuchin convent near the Place Vendôme. Robert staged “hauntings” using several lanterns, special sound effects and the eerie atmosphere of the tomb. The supernatural appealed to jumpy Parisians still dealing with the upheavals of the Revolution and facing an uncertain future under the Third Republic, and Robert successfully scared the pantalons off Parisians for six glorious years (!). Magic lantern shows eventually made their way across the Channel to England, and ultimately across the pond to the United States, where they laid the groundwork for spirit photography.

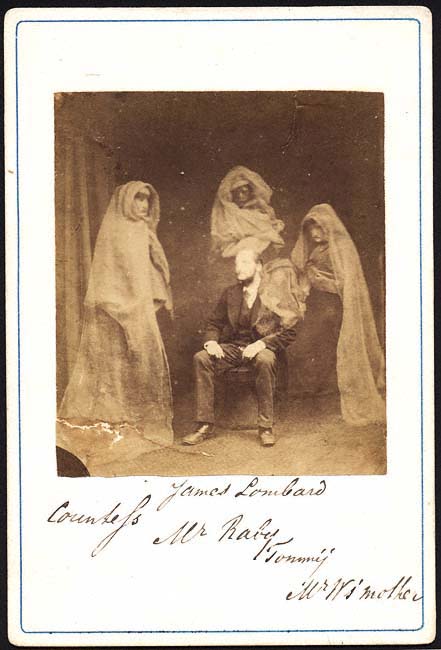

A few years later, in 1856, the London Stereoscopic Companywas photographing a carriage in a London Street, when their photo shoot was interrupted by a lamplighter and a small boy. In photography’s infancy, long exposure was required to capture an image; if someone came along into the frame, or got bored and walked out of frame, before the exposure was finished they created a “ghost” on the plate. Spectral images of the lamplighter and the small boy appeared on the plate, and the London Stereoscopic Company, being British and reasonable and all that, went on to produce a series of ghostly photographs with models trussed up in white sheets posing with actual people, just for a lark.

Meant to be amusements, their American cousins took them quite seriously – seriously enough, that is, to scam hundreds of people into believing the photographs actually captured the ghostly spirits. Just as the U.S was hearing its first murmurings of Civil War, and as Western expansion – that is, expansion into the unknown — continued apace, spirit photography grew wildly popular.

Australian artist Bridget Walker is interested in spirit photography and its relationship to early cinema techniques, fanstasmagoria, artifice, and B-grade special effects. An animator and artist living and working in Paris, Bridget is exploring animation as an idea — the condition of possibility and at the same time impossibility, offering a hybrid, reflexive perspective that oscillates in a space between ‘what if’ and ‘what is.’

I met Bridget after answering her irresistibly worded Craigslist ad: “would you like to be photographed with a spectre?” On a really really really cold Parisian Sunday, I met Bridget at Pont Sully, clenched my teeth against the cold and allowed myself to be immortalized with some spectres — Bridget is the spectre in all the photos, by the way. A soft-spoken, almost shy artist, Bridget and I continued to have a long conversation about the role of Victorian-era spirit photography versus spirit photography today, and the need to believe there is life after death becoming so overwhelming that people are willing to don white sheets and pose for photographs to prove it. While it is not Bridget’s intent to make any kind of social commentary about death and dying with her work, the photos themselves serve as a challenge to what you believe and what you want to believe, a doorway between what we know, and what we choose not to be aware is lying in bed with us.

Above images Copyright Bridget Walker, from The Soundless Spectre of Motion series.

***