One morning, my partner Kurt looked into our field and saw a black horse that wasn’t there. The horse looked just like our neighbor Jeremy Frith’s horse, and turned out to be a harbinger of his impending death.

A week earlier, Jeremy had been admitted to the emergency department due to concerns about his heart, but after EKG and blood pressure analysis his mind was put at ease. He was told that with a little bed rest he’d be just fine.

Tuesday morning I was outside shoveling around the hay trailer. Cheryl stopped in to tell us that she had just seen a number of emergency response vehicles at the Frith’s Mountain Meadow Farm. Just then Kurt came out of the house saying that another neighbour had called to share the sad news that indeed Jeremy had died. We fumbled to collect what we needed to go up the road.

People were gathered in the driveway in shock. I went into the house, suspecting that Jeremy’s body had already been removed by the first responders, who must have tried to rush him to the hospital. My intention was to offer support to his wife Sue.

To my surprise, there on their bedroom floor lay Jeremy – his head cradled in Sue’s lap. He was still warm, only recently pronounced dead. He looked wonderful (if slightly pale). There was nothing grotesque about his appearance at all. In fact my thought at that moment was, “how can someone who looks so strong and healthy be dead?” My impulse was to go closer to touch him.

Medical personnel were still around and since the death was unexpected, the police were conducting an investigation. It was difficult to witness Sue’s experience, but I refused to comply with those who conspired to “protect her” by insisting that she come downstairs to the living room for tea. Instead I chose to hold space for what was naturally unfolding.

Sue’s world was turned upside down, and she fretted about what would become of the farm, their animals, their gardens and herself. I sat down with her and Jeremy both, and said that all she had to think about right now was that this was the last chance she’d ever have to be with Jeremy’s body. When Sue was given permission to spend that time in any way that felt right for her, she opened to the experience so fully, and with such love, that being in their presence was an honour that I will never forget.

The local minister and I nodded at one another as we watched Sue communicate with Jeremy rather than about him. As a grief counselor, I recognized the important grief work that was being done. She looked into his face and imagined his answers to questions. “Do you know how much I love you?” She was holding his body as she made the difficult phone calls to tell his sons about their dad’s death.

Hours passed. Sue did everything a person could with that precious time. She agreed with the medical examiner that Jeremy must have an autopsy to try to attain some answers about his unexpected death, and by the time his remains were removed she felt his spirit was no longer embodied. One of the women who came to take Jeremy away was excited by the closeness of the dogs Kipper and Lucy who were cuddled at his side. She said that she had not seen animals that close in many years.

Hours passed. Sue did everything a person could with that precious time. She agreed with the medical examiner that Jeremy must have an autopsy to try to attain some answers about his unexpected death, and by the time his remains were removed she felt his spirit was no longer embodied. One of the women who came to take Jeremy away was excited by the closeness of the dogs Kipper and Lucy who were cuddled at his side. She said that she had not seen animals that close in many years.

Sue articulated that what she thought Jeremy would want- a burial at home, without embalming and without hiring professional services for anything that could be done by friends and family. It seemed like such a simple request and a perfectly natural response to the death of a farmer and poet and community activist.

Sue articulated that what she thought Jeremy would want- a burial at home, without embalming and without hiring professional services for anything that could be done by friends and family. It seemed like such a simple request and a perfectly natural response to the death of a farmer and poet and community activist.

That is how I came to embark upon a crash course in home funerals and burial here in Victoria County, Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. I can’t really recount all that was done, but I do remember that it was the DOING that felt therapeutic. I was compelled to assign anyone who said, “..if there is anything I can do,” a concrete task. That was effective and really got everyone working together in a way that would have made Jeremy proud. As a community, we made meaning of his death by cooperating to offer community centred, home based deathcare.

Friday morning Jeremy’s sons met in Halifax and went to the medical examiner’s office as well as the office of vital statistics to obtain a death certificate. Friends had been sent the night before with a van to pick up Jeremy from the morgue and placed him in a coffin that had been made on Thursday by other friends in Jeremy’s own wood shop. There was a palpable sense of excitement and adventure about the whole thing which was enhanced when the medical examiner told me that her understanding of her job was affected by the fact that in her career no one had ever come to retrieve the body of someone they knew!

It was winter, and Jeremy’s coffin was placed upon two sawhorses on the farmhouse porch overnight while the community gathered for a party that might also be called a wake or a home vigil. We sang and read aloud from his collection of Uniquely Bermudian poetry.

We didn’t open the coffin because the medical examiner made us promise we wouldn’t in case we might have been traumatized by the appearance of Jeremy’s body following autopsy. That was OK. No one said they wanted to see him, but since then we have wished that we had removed his remains from the plastic body bag from the morgue so that his home burial was greener. If only I had known then what I know now about the rights of a family to care for their own.

On Saturday morning our good ‘ol farm truck acted as a hearse and we all gathered at the community church at North River Bridge for a service. Sue had started a book at the wake in which she invited people to share thoughts and memories about Jeremy. At the service she read what my 8 year old daughter Naomi had written; “I thought about Jeremy at school today because we had our Christmas turkey dinner – and the carrots were terrible.”

On Saturday morning our good ‘ol farm truck acted as a hearse and we all gathered at the community church at North River Bridge for a service. Sue had started a book at the wake in which she invited people to share thoughts and memories about Jeremy. At the service she read what my 8 year old daughter Naomi had written; “I thought about Jeremy at school today because we had our Christmas turkey dinner – and the carrots were terrible.”

Jeremy worked his whole life so that a little girl like her would understand the difference between a fresh, locally grown, organic carrot and a “commercialized” one. Indeed, Jeremy has fed us well.

I’ll never forget the view as the coffin left the church and the white doors opened to reveal a beautiful snowstorm which was so severe that we commented; “as this story is retold over the years, surely no one will believe us!” It was nuts. Sue was lying on top of the coffin in the back of the truck for the last of many thousand drives up the Meadow Road with her husband. We couldn’t see 10 feet in front of us. The van which had been used to pick up Jeremy’s remains in Halifax slid off the road near the bottom of our horse field; ironically, right where Kurt had “seen” Jeremy’s horse 2 weeks earlier. There was congestion and even a collision- unheard of on this very remote, rural road.

The plan was to have a home burial upon arrival, but Jeremy’s interment was postponed while everyone took shelter in the house to recuperate, and the tractor had just broken down in the process of clearing the road to get access to the grave which Sue had picked for its beautiful view of the surrounding landscape.

The plan was to have a home burial upon arrival, but Jeremy’s interment was postponed while everyone took shelter in the house to recuperate, and the tractor had just broken down in the process of clearing the road to get access to the grave which Sue had picked for its beautiful view of the surrounding landscape.

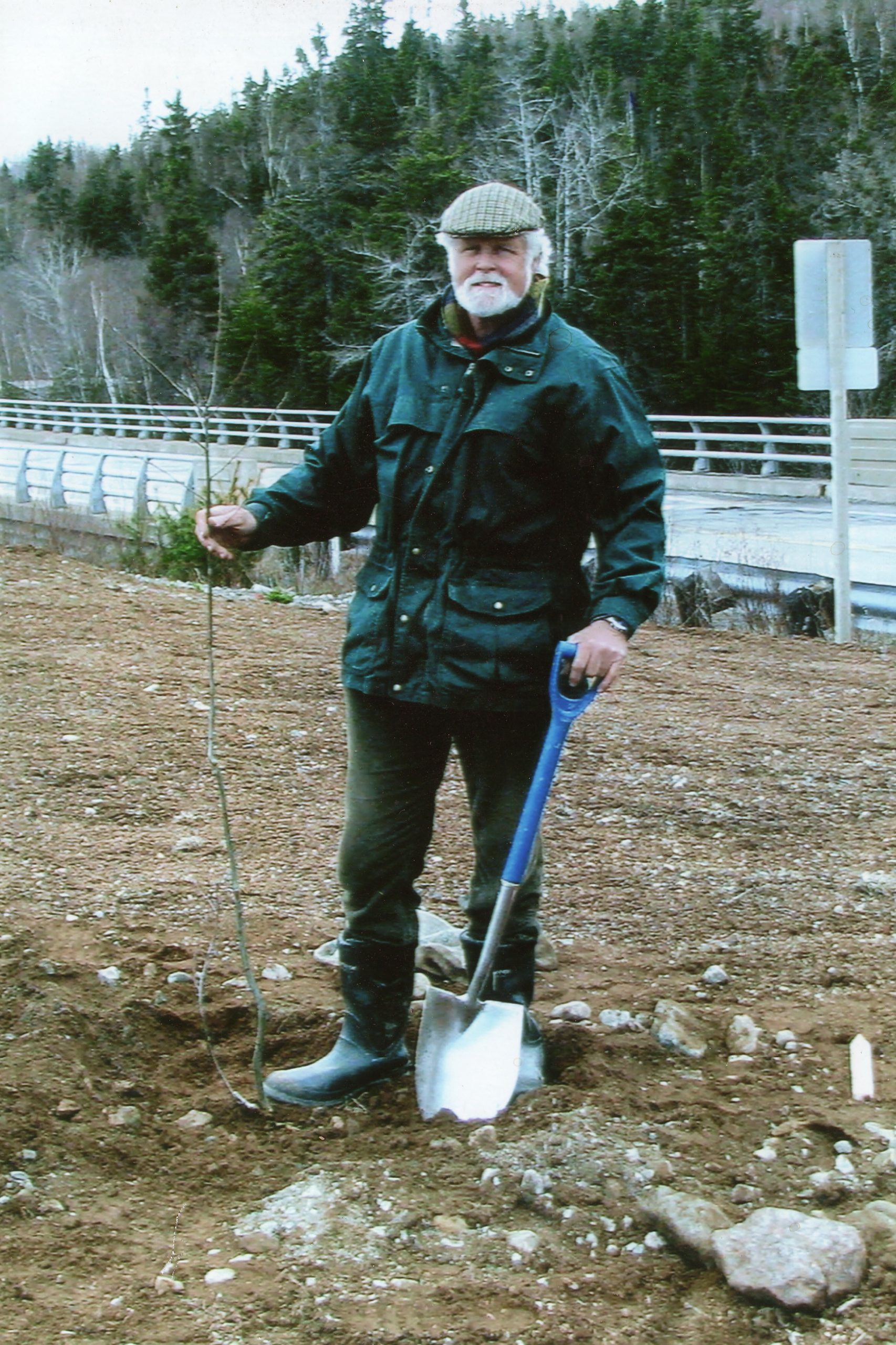

When the weather subsided a little we proceeded to graveside. The coffin was lowered and everyone gathered, singing and shoveling dirt into Jeremy’s grave with one of the many shovels we had found around the farm. We all took turns. During this process a patch of clear blue sky opened up. A bottle of whiskey was passed around and someone poured some on the ground in which Jeremy’s body now lies, near his deceased horse, also named Whiskey. Sue now tends vegetables there in addition to flowers and an Oak tree.

I’m sad and angry about the death of a good friend. As I remember him I recall that there was a vitality to Jeremy that might have occasionally been misconstrued as arrogance, but to my way of thinking an arrogant man is closed off to change; whereas Jeremy was always wide open. I believe that he would have been open to the changes taking place in the funeral industry, and I know he would be pleased to be the one to set an example of how enriching a home funeral can be in this day and age in rural Cape Breton.

I’m sad and angry about the death of a good friend. As I remember him I recall that there was a vitality to Jeremy that might have occasionally been misconstrued as arrogance, but to my way of thinking an arrogant man is closed off to change; whereas Jeremy was always wide open. I believe that he would have been open to the changes taking place in the funeral industry, and I know he would be pleased to be the one to set an example of how enriching a home funeral can be in this day and age in rural Cape Breton.

How could I have known that his death would impact my life so! As I reflected on the events described above the only words that seemed to capture the essence of what happened related to the home birth movement. Since that time the story of Jeremy’s home based deathcare has helped to shape a burgeoning discourse called Death Midwifery in Canada which I feel honoured to be involved with.

Below is what I wrote in Jeremy’s book:

We’ve seen each other almost daily since we moved to our homestead near to his. We trade fresh goat’s milk for precious organic vegetables. Jeremy helped me to understand why there is no exchange more sacred than this.

Cassandra Yonder lives on a self-sustaining homestead in Nova Scotia, Canada. She is a practicing Death Midwife, focusing on home funerals and alternative body dispositions. Cassandra is a Canadian representative to the National Home Funeral Alliance.