My grandfather knew the dead were coming.

Thirteen hours before, a runner had come to his remote village in Guangzhou, China warning the people of their approach. The villagers finished up their business, gathered their children, and closed up their houses. As the streets darkened and the last of the windows were shuttered, the village waited in heavy expectation for who or what would soon be there.

With all the lamps turned off and only the light of the moon piercing the dark from the cracks between the shutters, my grandfather and his brother sat in their home, eager for any sign that the procession was near.

They waited well into the night, the entire village remaining obediently silent. And just when my grandfather thought the night might never end, that he was caught in some sort of Hell of forever awaiting the dead, he heard it: a gong.

My grandfather heard the rhythmic beat of a gong closing in on his village. Before long, another sound could be heard: the shuffling of feet. Dozens of feet pounding and stirring the dirt.

The sound of the gong and the feet filled the village streets. Creeping out from their hiding spot, my grandfather and his brother inched over to the window and peeked out.

They saw a line of corpses, lurching, hopping, swaying through the streets, to the beat of the gong. They saw white cloths covering the heads of the dead, faces positioned up and forward, supposedly looking toward their final resting place.

They saw Taoist priests “herding” the dead, keeping them in line; one brought up the rear, a couple flanked either side of the line, one was the leader of the procession, and one walked ahead beating the gong.

As the dead passed through, my grandfather and his brother, while curious, made sure to never stare directly at the corpses. It was said that if the living looked too hard at the dead in such a procession, that the corpse might latch onto that person and try to steal their energy or “Chi”.

Grandfather told of a girl who did not heed this warning, and stared too long at a passing corpse. The corpse became enamored of her, tried to make her his “Ghost Bride”, dragging himself toward her, reaching for her. The priests had to surround the corpse and say prayers over him for many hours before he would leave the girl and get back in line.

So the story goes anyway. It seems that every village had a similar tale.

Eventually the dead passed through my grandfather’s village, with all living souls left safe and sound to live another day. Life in the village returned to normal, and nobody spoke much of THE NIGHT OF THE HOPPING DEAD.

While it was not something to be ignored, it was just understood that these things do happen. Sometimes the dead process through your village in the middle of the night. Just behave yourself, don’t stare, and shut your mouth. What of it?

But what did my grandfather actually see?

For his entire life, this was his only “spooky story”, one that he adamantly maintained was true. Skeptical, stoic, and reserved, he swore that he did not see ghosts or spirits or demons that night, he saw the walking (hopping) dead.

While it would be easy to write off my grandfather’s story as just one of old-world superstition or even a child’s nightmare, as it turns out there may be more than a little truth behind what my grandfather saw almost 100 years ago in Guangzhou.

No, I’m not saying that my grandfather saw a line of corpses reanimated by the power of prayer parading down the main street of his village. But what I am saying is that maybe my grandfather saw what was meant to trick people into thinking they were seeing a line of corpses reanimated by the power of prayer.

For almost as long as there have been dead people in China (so a long time) it’s been believed that that a person’s journey does not end in death. When a person dies they must return to the soil from whence they came. It didn’t matter if a person died 10 miles or 10,000 miles from their birth dirt, their body had to get back there. If a person was not properly buried in their home soil, family and friends risked having an angry, wandering spirit on their hands.

But getting a corpse back home wasn’t always easy. Transport by train or car could be very expensive. So obviously the only option was to have the corpse carry itself home.

This could be accomplished in two general ways: either by herding a corpse or walking a corpse.

The first practice of “herding” or driving a bunch of corpses involved assembling a number of corpses that needed to be delivered to a specific village or region. Taoist priests (or people calling themselves Taoist priests) would begin by praying and chanting over the dead so as to “possess” them into walking.

Much of this was for show, so that people would believe that yes, the corpses were actually being reanimated, and yes, they should keep their distance. It was all part of setting the stage for a swift, uninterrupted transport of the dead. Not to mention it only added to the priests’ status and AURA OF MYSTERY if people believed they actually had powers over corpses.

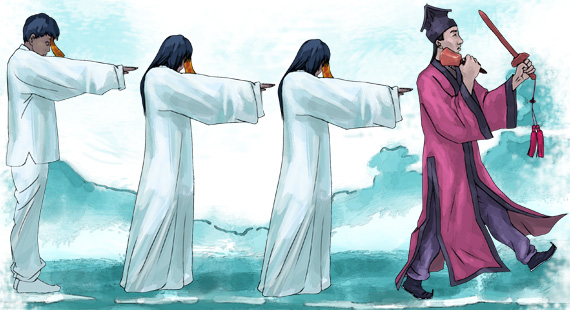

In a single file line, corpses would be tied to bamboo poles, one on either side of their upright bodies. Then, the ends of each pole would be hoisted onto the shoulders of a man at the front of the line, and a man at the back of the line, and off they would go.

As the men walked with the poles on their shoulders, it appeared as if the dead were shimmying, shaking, and hopping along on their own. A priest would head up the front of the procession and ring a bell or beat a gong in order to warn people of the coming dead.

This gave folks a chance to hide themselves or look away, as encountering the dead in Chinese belief is bad luck. Plus there was also the whole “steal your Chi/be my Ghost Bride” thing to contend with.

Conveniently, with everyone cowering and averting their eyes, nobody would get a good look at how the dead were moving. Add in the fact that the priests typically moved the corpses in cold weather and in the middle of the night, and you have a perfect recipe for speedy travel devoid of gawkers and maximum urban legend payoff.

If you know your audience, and shroud your activities in a thick layer of plausible superstition, you too could move the dead!

It’s very likely that my grandfather saw this sort of “herding” procession of corpses. He may have absolutely seen the dead making their way home, perhaps just not in the magical way he suspected.

Another way to move the dead would be via a corpse walker.

Corpse walkers were people whose job was to literally walk dead bodies home. While it is hard to find official records of “professional corpse walkers”, this business has been a part of Chinese culture for hundreds of years. As recently as the mid 20th century, there were reports of corpse walkers in China.

Like the herding of corpses, the details of corpse walking hide partly behind superstition.

When a corpse had to return home, a corpse walker was charged with “magically” reanimating the corpse and guiding it to its grave. People tell of seeing a corpse, dressed in a long black robe, obediently trudging behind a corpse walker.

The corpse walker carried a white paper lantern and a basket of fake money that he intermittently showered upon the ground ahead of the corpse. This was to bribe the deceased’s way into the next life, known as “buying your way into the other world”. As the corpse walker marched onward, he chanted something like, “Yo ho, yo ho” mixing in directions for the corpse following him.

The corpse itself loomed large, its head covered, its face beneath a mask. Everywhere the corpse walker went, the corpse was sure to follow.

People avoided the walking corpses and the corpse walkers in much the same way they avoided the herded corpses, keeping the corpse walkers’ secrets properly protected.

But what were those secrets?

While necromancy and folk know-how were part of the mystique of the corpse walker – author Liao Yiwu talks of having a black cat walk over a corpse “generating static electricity that would make the corpse move like a puppet” – the act of walking the dead was surprisingly simple.

Corpse walkers worked in pairs. One was the leader, the “walker”, one had the corpse hoisted upon his back, he was the “carrier”. The carrier’s job was also to masquerade as the corpse. Since the corpses were very heavy, and the walkers often had to travel for months at a time, the pair would regularly trade off who had to carry the corpse. The weight of a corpse on the corpse carrier also accounted for what appeared to be the corpse’s stiff gate.

Because the corpse carrier was hidden under the long, dark robe covering both him and the corpse, he used the corpse walker’s lantern – day or night – to guide him. To keep the corpse as fresh as possible, the corpse walkers only travelled during winter months, and put mercury into the corpse’s orifices to fend of decay.

For most of China’s history, it seems that corpse walking was a good way for an able-bodied person to earn money. It wasn’t until the rise of Chairman Mao and the Communist Party of China that corpse walkers became seen as “counterrevolutionaries” or “engaging in superstitious activities” and could face severe punishment, even death. Liao Yiwu writes of a pair of corpse walking brothers reported to the People’s Liberation Army who were arrested and jailed (in the same cell as the corpse they were meant to walk).

During an escape attempt, one brother was killed. The surviving brother buried him and was sent back to their home with only a death certificate. Sadly, there was no corpse walker for the corpse walker.

While corpse walkers may not have always been the most upstanding members of society (corpse walking was sometimes connected to smuggling or other unsavory practices), it was an accepted profession. Corpse walkers did what others couldn’t or wouldn’t do.

Corpse walkers and corpse herding priests provided a service. They let the living put what felt like a safe distance between themselves and the dead. Concealed beneath a warm cloak of superstition, the corpse walkers and corpse herders allowed people to focus on the mourning or spiritual aspects of death, instead of the cold reality of corpse transportation.

And really, the theater that the corpse transporters provided was just as valuable as the actual transportation. They made death and what happens to you after you die a thrilling, chilling part of the cultural conversation.

Sometimes the dead would walk through your village, that’s just how things worked. You paid them their due, you behaved with respect, but at the end of the night, it was only death passing through, and you’d live to see another day.

Louise Hung is an American writer living in Japan. You may remember her from xoJane’s Creepy Corner, Global Comment, or from one of her many articles on death, folklore, or cats floating around the Internet. Follow her on Twitter @LouiseHung1

Resources

The Corpse Walker: Real-Life Stories, China from the Bottom Up by Liao Yiwu, translated from the Chinese by Wen Huang The World of Chinese Magazine, “The Real Walking Dead” by Weijing Zhu