We moderns live in a sanitised blur of white smells, but scent was essential to our predecessors. Olfaction links us to our most primordial fears as well as our deepest desires. To the pre-Modern nose, time was marked with scent; sacred space was delineated with scent, the foul and the divine were understood by how they smelt. The link between offensive odours, the body, and immorality is well established in the psyche of Western society. The miasma that was thought to cause the plague was blamed as much on witches poisoning wells as on the immorality of the community leading to the fetid stink they believed caused death. Even today there are vestiges of Miasma Theory in the popular imagination, hence the frequency of lemon and lavender in Western cleaning products, two popular plague preservatives. It’s not really clean unless it smells clean. Our ability to smell connects us to the animalistic acts of the body, yet almost every religion also employs fragrance to create a sense of spiritual otherworldliness. Our ability to smell is exceedingly mundane and magical at the same time.

The putrefaction of the body has long been presented as theological evidence of the transient and base nature of the material world. Susan Ashbrook Harvey in her book Scenting Salvation recounts the tale of a monk in love with a woman that died and “cures” himself of his desire and grief by digging up her body, soaking his garments in the fluids found in her coffin and smelling the repugnant items whenever tempted. The moral of the story is clear; earthly desires lead to nothing but the rot of the grave. While a siren song or a beautiful temptress may use superficial beauty to hide evil intentions, scent is much more straightforward. If it stinks it’s earthly and therefore wicked if it smells nice, it’s connected to the abstraction of the spiritual world and is therefore good. Yet, if corrupt smells are a sign of a corrupt nature, what happens when a holy person dies? It is in this Western mind-body dualism that the concept of the Odour of Sanctity is born.

The Odour of Sanctity, formally known as Osmogenesia is a supernaturally pleasant odour coming from the body or wounds, usually after death. It was presented as a physical sign of the spiritual superiority of the person. While gods and supernatural beings are often associated with pleasant aromas, the Odour of Sanctity is attached explicitly to human bodies and is primarily a Western phenomenon. The concept arose in the early Middle Ages with roots in the early Christian communities of Greece and Egypt, but it didn’t gain considerable traction as a sign of sainthood in the Catholic Church until the Early Modern period. It wasn’t formally recognised as part of the beatification process until 1758 by Cardinal Lambertini (who later became Pope Benedict XIV) and has since been downgraded to a favourable sign of holiness. While the Odour of Sanctity is strongly associated with, and for a time was a sign of, incorruptibility the phenomenon was not limited to officially venerated saints in Catholicism or the Eastern Church and developed a robust apocryphal pedigree around heretic preachers and saints alike. Modern theologians will say that the Odour of Sanctity is metaphorical, that it’s an ontological state of being. While that may be true now or for religious scholars of the past, it indeed was taken, and preached, as a literal odour to the laity.

A dead body touched with the Odour of Sanctity can’t just smell ok. It has to possess the mysterious presence of a supernaturally pleasant odour. The scents can be brief or persistent, attached to the body, grave, water the body was bathed in, or objects the person touched. In the case of St. Padre Pio, his spectral scent of roses and pipe tobacco visited people after his death and was considered a sign of his saintly intercession. All Odours of Sanctities are described as sweet, with notes of honey, butter, roses, violets, frankincense, myrrh, pipe tobacco, jasmine, and lilies being the most frequently reported accompaniments. The scent is also always culturally specific and deeply intertwined with symbolism.

St. Polycarp the 2nd century Bishop of Smyrna was martyred by being burned at the stake. In the late Medieval telling of his death, his burning body was said to smell like a brazier of frankincense and myrrh instead of charred flesh. Thereby making an olfactive connection between the incense sacrificed in the Holy Temple, the gifts of the Magi, and Polycarp’s martyrdom. The eleventh century, Marie of Oignies’ body smelt of buttery pastries even though she sustained herself on nothing but communion wafers for the last few months of her life and died due to self-induced starvation.

St. Polycarp the 2nd century Bishop of Smyrna was martyred by being burned at the stake. In the late Medieval telling of his death, his burning body was said to smell like a brazier of frankincense and myrrh instead of charred flesh. Thereby making an olfactive connection between the incense sacrificed in the Holy Temple, the gifts of the Magi, and Polycarp’s martyrdom. The eleventh century, Marie of Oignies’ body smelt of buttery pastries even though she sustained herself on nothing but communion wafers for the last few months of her life and died due to self-induced starvation.

One of the most popular of the fragrant saints, St. Therese of Lisieux smelt of lilies, violets and roses upon her deathbed. Her most often attributed quotes is, “The splendour of the rose and the whiteness of the lily do not rob the little violet of its scent…If every tiny flower wanted to be a rose, spring would lose its loveliness”. It also should be noted that during Therese’s lifetime violet absolute was synthesised, making a material that was once the most expensive fragrance component in the world, affordable for all and the de rigueur fragrance of respectable women. To the Victorian palette, violets represented chastity, modesty, and feminine virtue. Lilies and roses also have a long association with Jesus and Mary. Therese’s Odour of Sanctity creates an olfactive tableau of Therese, the respectable modest female, alongside the Virgin Mary and Jesus. Before 1875 however, the scent of violets would not have been readily identifiable to the general population, and no Odour of Sanctity is associated with violets in any primary sources before that time. There is also an active association between Osmogenesia and Stigmata, with the floral odour emanated from the wounds. Stigmatic Osmogenesia in every case is reported as the smell of roses, which again is deeply symbolic with the wounds of Christ.

While there is no way of knowing just how many people the Odour of Sanctity was associated with, in the Late Medieval and Early Modern periods ascetic mystics make up a large population of those afflicted with this post-mortem perfume. In particularly female mystics that lived cloistered lives. These women’s bodies suffered through harsh asceticism and self-inflicted mortification. Yet through the isolation, hardship, poverty, and virginity, these mystics sought to control their bodies and transform them into sacred vessels. It, therefore, makes sense from their perspective that, if successful, the discarded vessels of these perfected souls should already be touched by a whiff of Paradise. The association of the Odour of Sanctity with cloistered women parallels the profane eroticism of the earthly woman with the chaste eroticism of the sacred woman; while the worldly woman’s corpse corrupts by its nature and stinks, so the heavenly woman’s body remains pure and fragrant. However, the conversation is still about a woman’s body.

St. Teresa of Avila was another fragrant ascetic and mystic. She lived in seclusion, practised tri-weekly self-flagellations and didn’t wear shoes. The moment she died her bedside attendants said the room filled with the scent of roses that grew to saturate the building. The convent smelt like it had erupted into bloom and cascades of invisible blossoms poured from the windows. Her grave held the scent of roses for eight months. The sensuality of the story is part of the appeal. St. Teresa would never have done something so showy in life, but in death, the Odour of Sanctity makes it permissible as divine sensuality just as Bernini captures the divine sensuality of Teresa’s transverberation in the Ecstasy of Saint Teresa. So what was it that all these people were smelling? If we couch the religious explanation, are there any earthly ones? Well, firstly many of the accounts of the Odour were written down centuries after the individual’s death and came out of folk traditions. So there is undoubtedly some gilded lilies. For others, the nose like any of our senses can be fooled especially when primed. In a time of sorrow and acute stress, a smell that was imperceptible moments earlier can become overpowering. One could rationalise the sickly sweetness of early decay or illness as divine honey. Of course, the more one tells a story, the more it turns to legend and becomes grander. So the whiff of sweetness becomes an eruption of flowers.

What I think is of interest is the overlap of female religious ascetics associated with both the Odour of Sanctity and Anorexia mirabilis (the miraculous lack of appetite). Anorexia mirabilis was a form of religious anorexia that led women and girls during the late Middle Ages and Early Modern periods to engage in prolonged fasts, not in the name of socially acceptable beauty, but religious purity. These women abstained from eating for long periods of time or attempted to sustain themselves on communion wafers. Some, like Angela of Foligno and Catherine of Siena, refused food but reportedly ate the scabs and drunk the pus from sores of hospital patients. While they certainly were exceptions, their religious communities already practised fasting and food restriction that was exploited by particularly devout practitioner in pursuit of spiritual perfection.

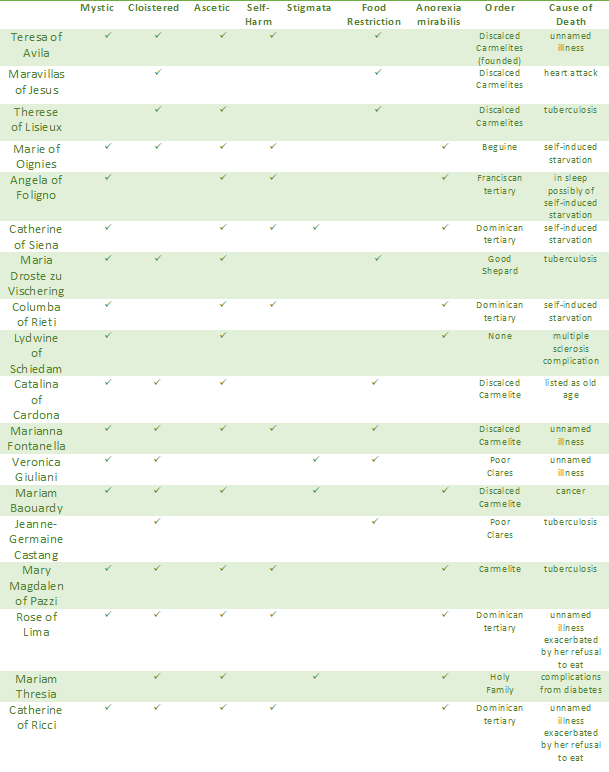

In fact, the medical explanation for the Odour of Sanctity is that it is nothing more than Ketoacidosis. Ketosis is a natural process that occurs when the body runs out of glucose and starts to metabolise fatty acids. This progression volatilizes acetone which produces a mildly sweet smell, unrecognisable to most. Should this devolve into the pathological metabolic state of Ketoacidosis from alcohol abuse, starvation, or diabetes, the acetone becomes detectable, even overpowering. Someone engaged in prolonged fasts or dying while in an advanced state of Ketoacidosis would have a strong sweet smell. In examining the lives of 18 women associated with the Odour of Sanctity, who lived over a 700 year period; all 18 practised some form of food restriction while 10 entered into the pathological territory of Anorexia mirabilis. Seven cases either died due to self-induced starvation or illness complicated by refusing to eat, which supports the Ketoacidosis hypothesis. However, these women had many other similarities. 14 were mystics, 15 practised ascetic lifestyles, 14 were cloistered or hermits, 12 practised some form self-harm as self-mortification or stigmata.This paints not only a medical profile but a social one. Seven of the cases were part of the Carmelite Order (6 Discalced, 1 O. Carm) 2 were named after St. Teresa of Avila who founded the Discalced Order. The Discalced Carmelites were also known for their extreme austerity. Even if Ketoacidosis wasn’t present at the time of death, it makes sense that women of the same order, leading similar lives, and looking to St. Teresa as a role model would also be associated with the same supernatural phenomenon as her at the time of their deaths. These women’s lives were dedicated to transcending their physical forms, and nothing is more corporal then the haze of human decomposition.

It is perhaps the ultimate epitaph for these women to have their corpses associated with the Odour of Sanctity. Personally, I’d prefer to lead a happy and healthy life and have the stench of my corpse reek to high heaven than to ever even attempt to achieve such perfection.

Some of the women associated with the Odour of Sanctity

Nuri McBride is a Research Fellow at the Minerva Centre for the Study of Law under Extreme Conditions, where she investigates how society, specifically, how the law, copes with mass death events and the refugees these events create. Nuri is a 5th generation Metaharet and has served her community for 15 years. She is also active in natural burial and death positivity education. As well as advocating for an inclusive approach to Jewish death traditions. While studying as journeyman perfumer in her free time Nuri started her blog which examines the use of olfaction in death rituals around the world. Follow Nuri on Twitter Instagram

Further Reading:

- The Foul and the Fragrant: Odour and the French Social Imagination Alain Corbin [available in both French and English]

- Scenting Salvation: Ancient Christianity and the Olfactory Imagination Susan Ashbrook Harvey

- The Odor of Sanctity and the Hebrew Origins of Christian Relic Veneration Lionel Rothkrug

- Odor and Power in the Roman Empire David Potter

- Odor of Sanctity: Distinctions of the Holy in Early Christianity and Islam Mary Thurkill

- The Odor of the Other: Olfactory Symbolism and Cultural Categories Constance Classen

- Body and Soul: Essays on Medieval Women and Mysticism Elizabeth Alvilda Petroff

- Le Parfum Comme Signe Fabuleux dans les Pays Mythiques Annick Lallemand In Peuples et pays mythique [French]

- Parfums Magiques et Rites de Fumigations en Catalogne (de l’ethnobotanique à la hantise de l’environnement) Jean-Louis Olive [French]