Go behind the scenes of this article with author Paul Koudounaris, as he talks about Uncovering Pet Death’s Greatest Mystery, on our podcast Death in the Afternoon.

The Rainbow Bridge: The True Story Behind History’s Most Influential Piece of Animal Mourning Literature

If you meet your pet in the afterlife, thank Edna Clyne-Rekhy

Courtesy of Edna Clyne-Rekhy

Snapshot of Edna and Major

Edna Clyne was nineteen years old and living in Inverness, Scotland, in 1959, when her Labrador Retriever named Major died. He was her first dog. Not the family’s first, there had been others in the house, but the first that had been hers alone. “He was a very special dog,” she told me, “Sometimes I would just sit and talk to him, and I felt that he could understand every word I said.” Her mother used to ask how Edna had trained Major to be so gentle and obedient, and she still laughs about the question, explaining that she had never trained him at all, it was natural between them. Many of us who have had pets have known one like that, the one that truly understands, the one who lives as a piece of us.

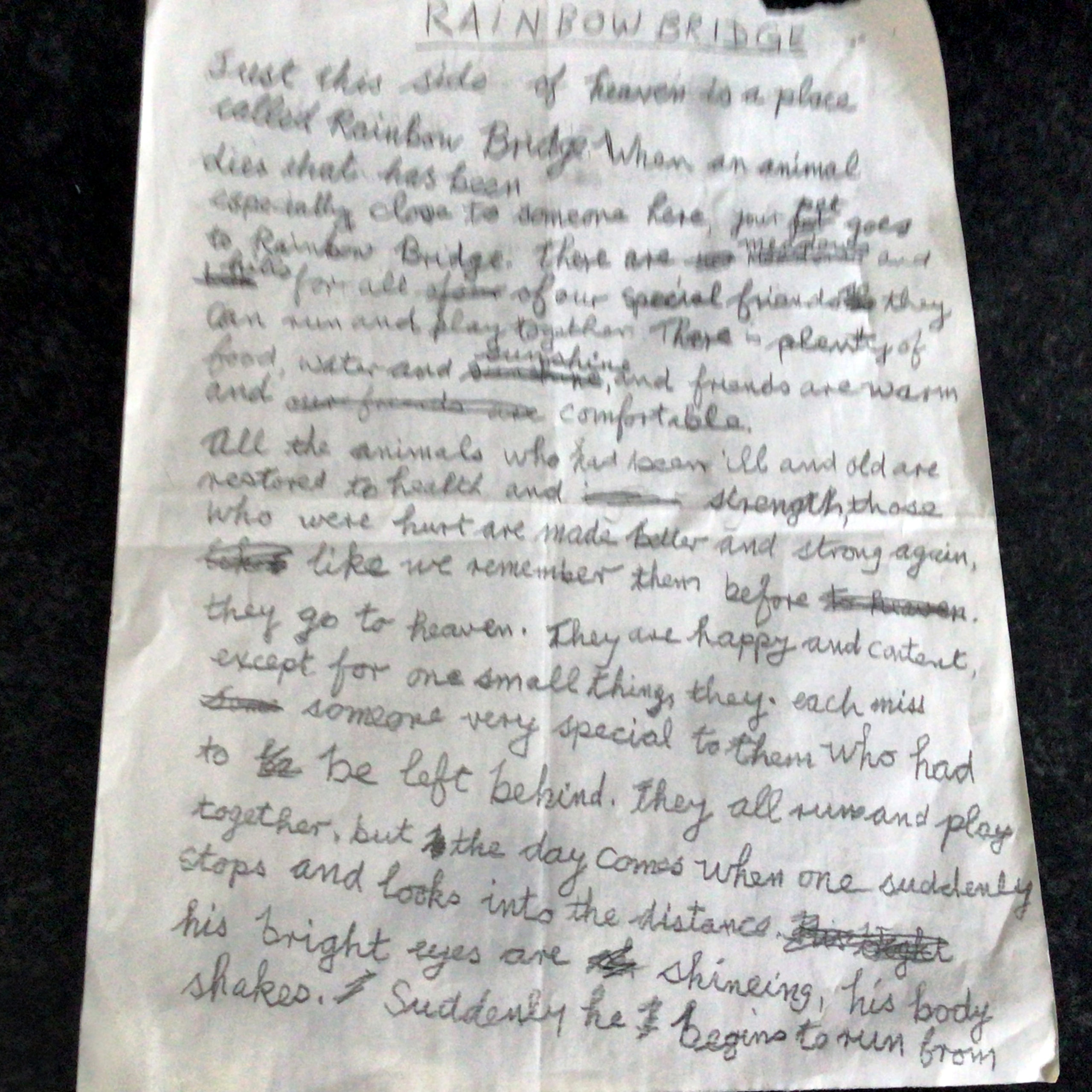

Courtesy of Edna Clyne-Rekhy

Edna’s original copy of The Rainbow Bridge, handwritten on a sheet of notebook paper

We can also understand the pain of their passing. The day after Major died Edna felt a compulsion. There was something she needed to write, and while she hadn’t preconceived any of it, it was there, words longing to be heard. She remembers it being a warm and wonderful feeling, like Major himself was guiding her in what to write. There was a notebook nearby and she pulled a piece of paper from it and began. When Edna filled the page she turned it over—only to find there was already something written there. Oops, she had in her haste inadvertently pulled a page from her sister’s notebook. No matter. She erased her sister’s words as best she could, and then filled half the page with her own until she was done. Then she turned the paper back over and put a title on it, two words: “Rainbow Bridge.”

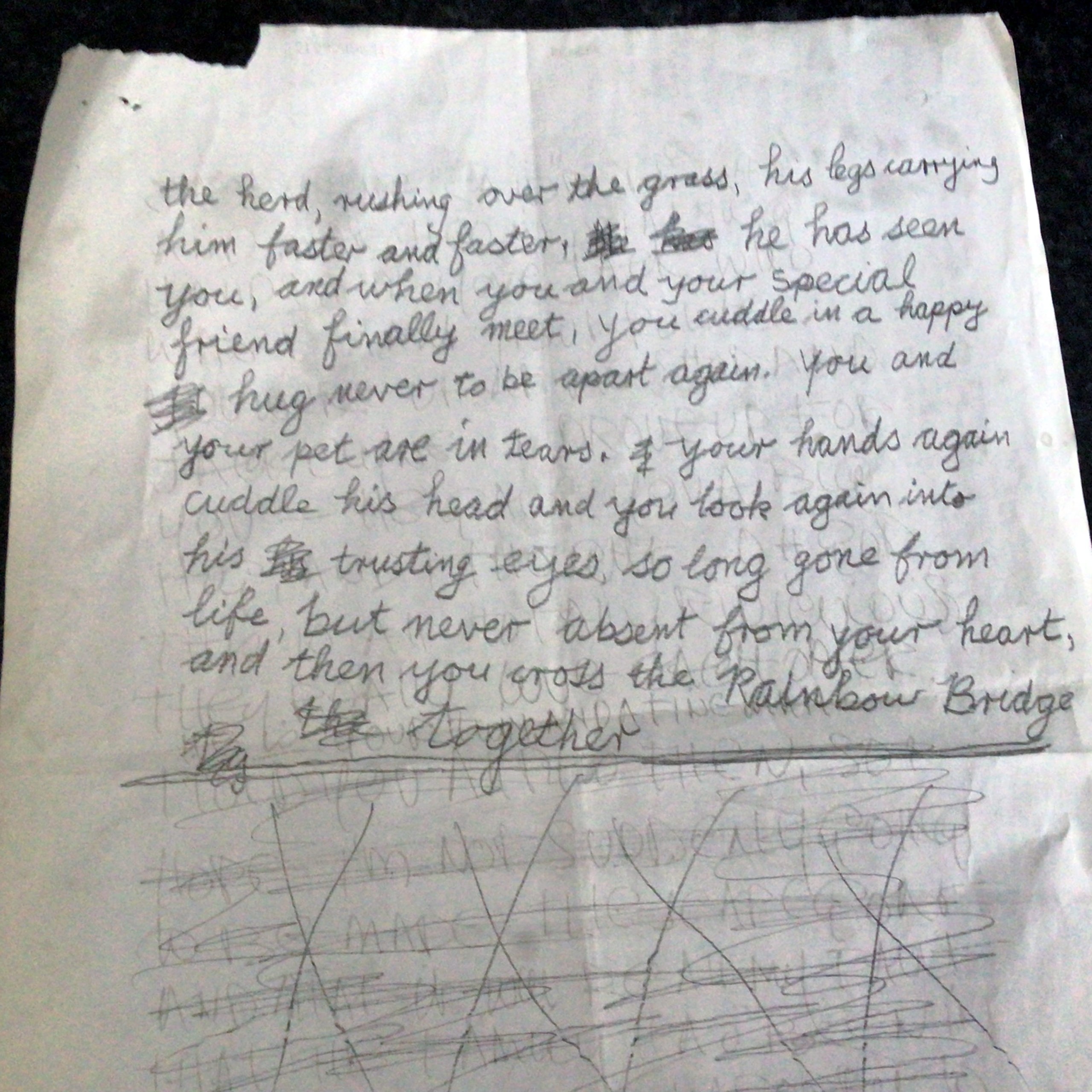

Courtesy of Edna Clyne-Rekhy

The back of Edna’s original copy of The Rainbow Bridge, handwritten on a sheet of notebook paper with her sister’s writing crossed out at the bottom

Yes, that Rainbow Bridge. It is probably impossible, at least in the English-speaking world, to have lost a cherished pet and have never heard of the Rainbow Bridge. The words composed by Edna at Major’s passing are nearly ubiquitous in the world of animal mourning. They are printed on sheets passed out to people when they pick up the ashes of cremated pets. Sympathy cards and posters are found with them. Snippets of the text are frequently used in epitaphs dedicated to beloved animals. Some pet cemeteries even have them inscribed for all visitors to see, on giant stone tablets that look like something handed by God to Moses. Her words are so well known that even though they are confined to grieving pet owners they comprise one of the most influential pieces of mourning literature ever written.

Photographed by Paul Koudounaris

Craig Road Pet Cemetery in Las Vegas

As a concept, what nineteen year old Edna envisioned is a kind of limbo where deceased pets are returned to their most hale form and cavort in newfound youth in an Elysian setting. But it is not paradise itself. Rather, it is a kind of way station where the spirit of an animal waits for the arrival of its earthly human companion, so that they may cross the Bridge together, to achieve true and eternal paradise in each other’s company, and to thereafter never again be parted. The Rainbow Bridge has been referred to as “chicken soup for the soul,” as a kind of simple comfort for grieving hearts.[1] This is not an unfair assessment, but it is also something much more.

Those who have grown up in Western culture, and especially under a Christian dominated spiritual system, have frequently been discouraged from believing that animals have an afterlife, the standard line being that non-humans lack souls, and therefore cannot enter Heaven or participate in eternity. In truth, this is in no way a canonical belief, and anyone who claims it to be is ignoring centuries of debate on the issue of animals and souls among religious scholars. It is not a simple matter, and that is no doubt why it has been grossly oversimplified and presented in one-sided terms: animals have no souls, there is no eternity for them. Yet to people who have found their greatest joy in their pets, how can there be a paradise without them?

And that is precisely why the Rainbow Bridge has become so popular. It serves as a kind of theological plug in. As an elastic concept that can be applied to any faith, it provides a clearly expressed means for us to reunite with our pets in the afterlife. In so doing, it gives hope where a person may have been previously acculturated to believe there was none. Yet despite the overwhelming popularity of the Rainbow Bridge, its author has never received credit. It is usually listed as anonymous, and if one tries to get to the source one must run the gantlet of a wide range of purported authors who have tried to claim it as their own.

Photographed by Paul Koudounaris

A grave marker for a dog named Allie Bille in Winterhaven, California which reads “I’ll meet you at the Rainbow Bridge.”

When nineteen year old Edna finished the original draft, and went through and crossed out a few words to swap them for others, she showed it to her mother. “My darling girl, you are very special,” was the response, although her mother also pointed out that it was a bit messy, and asked if she didn’t want to write it out again. Edna didn’t write it out again, the copy with the crossed out words was fine, it was true to the moment. She showed it to some other people who were close to her and then put the paper away, not showing it to anyone else for a long time.

Later she married Jack Rekhy, adding his last name to hers, and she showed it to him. Jack thought it was wonderful and suggested she publish it. But Edna didn’t want to, telling him it was something private between herself and Major. But it wasn’t so private that she couldn’t share it with friends. She decided to make a few copies. She didn’t have access to any sort of photocopy machine, so she typed them out individually and gave them to people she was close to. She never imagined that what she had written would go beyond that circle, but the people who were touched by her words shared them with others. Of course, Edna’s name wasn’t on it, and as more and more people shared the Rainbow Bridge it became cut off from its source.

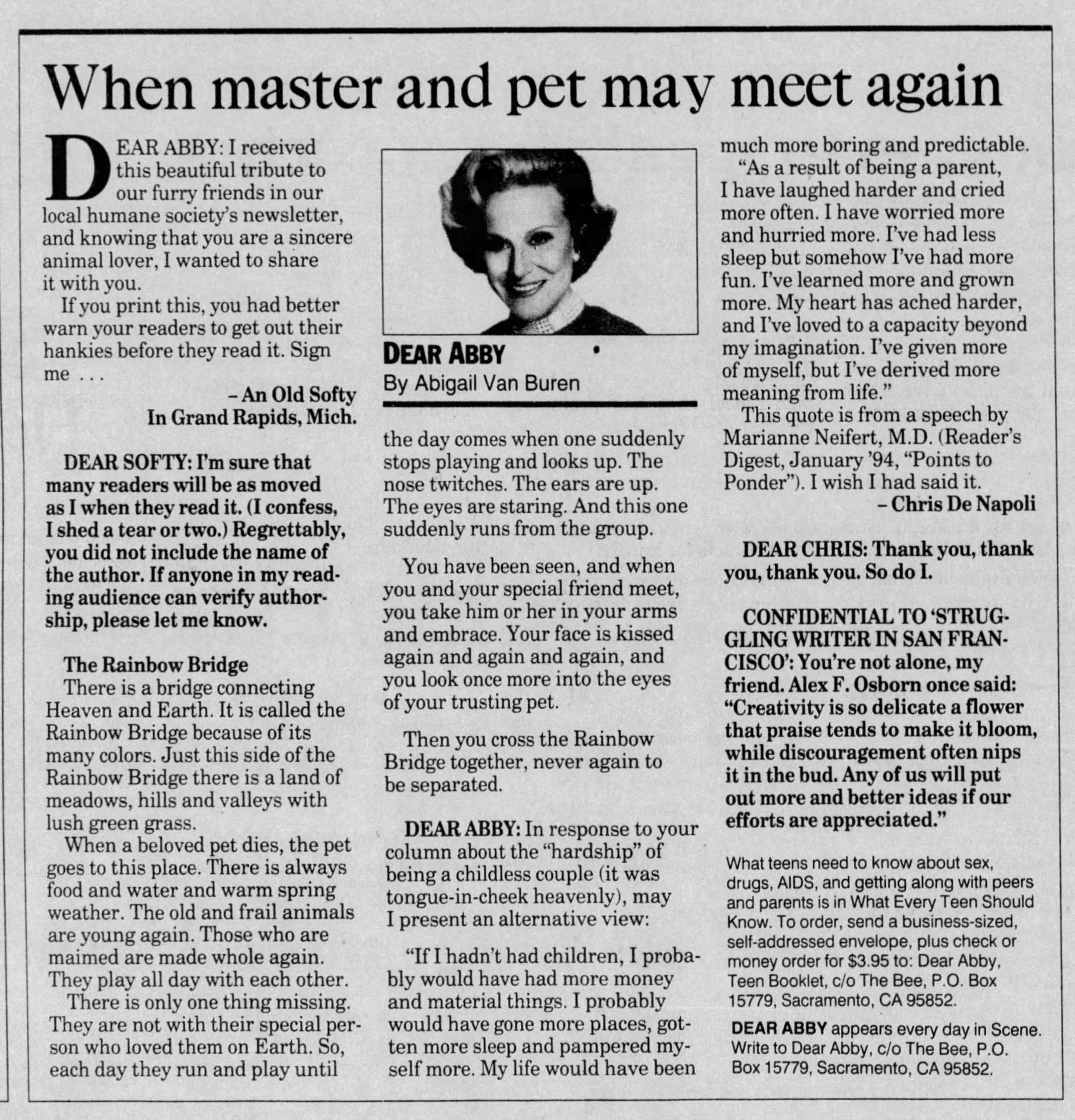

By the early 1990s it had crossed the Atlantic and was being shared by animal lovers’ groups in the United States. This was still a very small and obscure audience. But in early 1994 a reader who had seen the words printed in a Humane Society newsletter wrote to Dear Abby. The work of mother and daughter team of Pauline and Jeanne Phillips, Dear Abby was the largest circulation syndicated newspaper column in the United States, offering advice and words of wisdom to an audience of 100,000,000 readers. On February 20, Dear Abby printed the letter, which advised, “if you print this you had better warn your readers to get out their hankies before they read it,” and was signed by “An old softy in Grand Rapids, Michigan.” And underneath was the entire text of the Rainbow Bridge.[2]

The Dear Abby column as it appeared in the Sacramento Bee, February 20, 1994

It provoked an overwhelming response, mailbags full of letters from pet owners who had been touched, as if these words were exactly the ones they had been waiting all their lives to hear. The world now had the Rainbow Bridge—and the Rainbow Bridge had no author. Dear Abby recognized the oversight in publishing the text anonymously, and had in the same column asked her readers to please write in with a name so it could be properly credited and its creator recognized. None did, and it is unlikely any of them could have guessed that the author of the Rainbow Bridge was by that time already 35 years old and had been written by a Scottish teenager.

Lacking a single author, the Rainbow Bridge soon had many, as various animal experts and grief counselors stepped forward to claim the words as theirs. Booklets started to appear helping to justify their claims, although since none of them appeared before Dear Abby ran the text it is hard to see how they had any credibility. The United States Copyright Office lists fifteen separate claims under the title of Rainbow Bridge within five years of Dear Abby’s column. [3] Of course, this was all happening across the Atlantic so Edna had no idea any of it was going on. I told her that I had a book in my possession, published also in 1994, by an American author who said the Rainbow Bridge was originally the work of a Native American shaman, who had recited it to him while wearing a special story telling mask—she responded with a dismissive chuckle. [4]

There may not have been a shaman involved, but there is nonetheless something mythic about the text. With its author unknown to them, essayists have analyzed its components to reveal a wide range of potential sources for its imagery. The rainbow, especially in connection to animals, must be a reference to Noah and his Ark, it has been decided. And the bridge between realms is an allusion to the Bifrost Bridge in Norse Mythology. As for the idyllic setting filled with loving and peaceful animals, clearly that is derived from 11 Isaiah, which mentions how the wolf shall live with the lamb and the leopard lie down with the calf. Fitting all of this together seems like advanced stuff for the average teenager, and I prodded Edna about her influences. Surely she must have had a spiritual upbringing, or been immersed at a young age in the study of mythology. Absolutely not, she insists. The words really did just come to her in the compulsion to write, lost in the warm feeling that Major himself was directing her hand.

But then she offers more. Major’s passing was not her first encounter with death. Her father, an architect, died when she was fifteen. She was angry at him for leaving. Alone with the body, she looked down at him in his coffin, hands folded over his chest and head lead cold to the touch, and let him know exactly how she felt. Her anger was answered by an epiphany. As she stared at his face she suddenly envisioned his eyes wide open staring up at her, and heard his voice. “Dinn-a worry,” he told her, a Scottish phrase meaning don’t worry, then “athing’ll be a-richt,” everything will be alright. She felt a sudden, warm feeling, and at that moment her mother peered into the room to check on her, and told her the exact same words she had just heard in her father’s voice. At that moment she knew that there must be some kind of god, that something benevolent did exist beyond us, and she has never doubted it since. And that warm feeling she felt at that time was the same warm feeling that overcame her when she felt the compulsion to write the Rainbow Bridge.

Courtesy of Edna Clyne-Rekhy

Edna today, with her dogs Zannussi and Missy

Edna is 82 years old now. It has been 63 years since she sat down to memorialize Major, but she has never been without the page on which the words were written. There is a box of odds and ends in her attic. It’s marked, “If you can’t find it, it’s in here,” and that is where the original is now stored. She confessed that when she took it out to take photos of it for me that she started to cry, the old piece of paper still carries that much emotional power for her. I asked her thoughts on the strange journey those words have taken, and whether she harbored any resentment about her authorship of them having been forgotten. She told me it was wrong of people to try to claim it as theirs, and like anyone who has poured their heart into a text she’s not too keen on the alternate versions floating around, with people having changed some of her original prose.

More than anything though, she is simply flattered that something she wrote so long ago has resonated with such a vast number of people—the fact that it has comforted so many is the greatest possible homage to her love for Major. Not that she has ever fully understood the extent of her accomplishment. Edna had never even heard of Dear Abby until I mentioned the name and told her how the column shared her words with 100,000,000 Americans. She knew nothing about the inscribed tablets in pet cemeteries. She had also never heard the abbreviation ATB, I had to explain that it meant “At The Bridge,” and that there are entire mourning groups based around those three letters, which signify the pets waiting to meet their owners at a place she invented for Major.

But nothing took her aback as when I asked if she has any advice to share for people suffering from the loss of a pet—because she, is after all, the world’s greatest expert on animal mourning. She asked if I really thought that was true, to which I could only respond, “Well you wrote the Rainbow Bridge, didn’t you?” Her response was then immediate—get another pet. We discussed it, how the relationship with a new pet will never be the same as the relationship with the old one, but it can be equally special and loving in different ways. There’s no reason to deny yourself or another animal that love, your previous pet certainly wouldn’t have wanted you to live without it.

There would never be another Major, but Edna has indeed always continued to have dogs. She hasn’t lived in Inverness continually. There were several years in India, where Jack was a physician. They lived in Agra, not fifteen minutes from the Taj Mahal, and Edna used to rescue street dogs. After he retired they moved to Spain and bought an olive farm. She had dogs there too, and one day they came running to her. Something was up, and she followed them to the back of the house. There, inside the washing machine, was a young dog. He was an Andalusian Podenco, and he was hiding in there, badly injured, having been beaten by another olive farmer who was training him to hunt boar. She took in that one too, and called him Zanussi, after the name of the washing machine’s manufacturer.

It was in Spain that Jack first exhibited Alzheimer’s. They returned to Scotland, where he would eventually die from it, and Edna would once again write. A book called Zanussi and Jack, with a photo on the cover of Zanussi exactly as she had found him in the washing machine. And once again her words would be stolen, although this time she wasn’t flattered. The funds from the book were to go to an Alzheimer’s fund in memory of her husband, but it turned out a shady printer had been making his own copies and selling them behind her back, so she pulled the book, but hopes to put out a revised edition. (Note: the book is available both in Kindle and hard copy, but searching current online marketplaces only brings up pirated editions. This article can be updated if an official copy approved by Edna is released, but since we cannot be sure when that might happen, the author and editor suggest that if a person purchases a pirated copy they might also donate some percent of the purchase price to Alzheimer’s research, and thereby honor her original intentions.)

She still has Zanussi, who is now 11, as well as a Bichon Frisé, Missy, a professionally trained caregiver dog who is so thorough in her work that every night at 8 pm she brings forth Edna’s slippers, pajamas, and nightgown, one piece at a time, and gives a bark to signify that it is time to prepare for bed. Zanussi was at Edna’s feet when we spoke, and she offered to tell me a secret about dogs. Maybe it’s not so much a secret, and for Edna it is more like an essential truth. Certainly it is the truth which underlies the Rainbow Bridge itself, and why words written for Major over six decades ago have touched so many people, and no doubt will continue to touch them for generations to come. “If you love a dog,” she explained, “if you truly love it, it will always live on.”

As an addendum, we offer the Rainbow Bridge as transcribed from Edna’s original text written upon Major’s Death:

The Rainbow Bridge

By Edna Clyne-Rekhy

Just this side of heaven is a place called Rainbow Bridge. When an animal dies that has been especially close to someone here, your pet goes to Rainbow Bridge. There are meadows and hills for all of our special friends so they can run and play together. There is plenty of food, water, and sunshine, and friends are warm and comfortable. All the animals who have been ill and old are restored to health and strength, those who were hurt are made better and strong again, like we remember them before they go to heaven. They are happy and content except for one small thing, they each miss someone very special to them who had to be left behind. They all run and play together, but the day comes when one suddenly stops and looks into the distance, his bright eyes are shineing (sic), his body shakes. Suddenly he begins to run from the herd, rushing over the grass, his legs carrying him faster and faster, and when you and your special friend finally meet, you cuddle in a happy hug never to be apart again. You and your pet are in tears. Your hands again cuddle his head and you look again into his trusting eyes, so long gone from life, but never absent from your heart, and then you cross the Rainbow Bridge together.

Resources

[1] The quote is from Ann-Marie Gardner, “Animals: What is the Rainbow Bridge and why do we think dead pets cross it,” Washington Post, May 1, 1998; the article was syndicated and is found in several other American newspapers.

[2] The bulk of newspapers which carried Dear Abby ran the column on February 20, but because publication schedules vary some ran it later. The press clipping included here is from The Sacramento Bee. There were follow-ups to the original column. Dear Abby also published some letters from pet owners reacting to the text, and the column ran the Rainbow Bridge in its entirety again in 1998.

[3] These claims start in 1995 although it is clear that several were filed in 1994. It is unclear how many of them are attempts to claim Edna’s text since there had previously been copyright claims under that title, and completely unrelated—Rainbow Bridge had been used as the title of a text copyrighted by the Rajneesh Foundation in 1979, for example, and a copyright had also previously been held under that title for a piece of music used in the motion picture MASH. There is a dramatic increase in filings under Rainbow Bridge after the Dear Abby column, however, and in some cases influence of Edna’s text is obvious from the filings alone, as they include words like “afterlife” and “pets” in the notes.

[4] The book mentioned is William N. Britton, The Legend of the Rainbow Bridge, Savannah Publishing, 1994. Another claimant frequently cited is Dr. Wallace Sife, a professional grief counselor, who has stated the belief that the Rainbow Bridge was derived from a poem he wrote, apparently in the 1980s, called “Pet Heaven.” One claimant of the text, an Oregon man named Paul Dahm, is said to have copyrighted a version of the Rainbow Bridge in 1994, although this does not appear among registered copyrights. He published a book in 1997 called The Rainbow Bridge with Running Tide Press in Oregon, and that book is listed with the United States Copyright Office in that year.

Paul Koudounaris is a founding member of The Order of the Good Death. He has a PhD in Art History and has written three books about the use of skeletal remains in sacred spaces, Empire of Death, Heavenly Bodies, and Memento Mori. When he’s not hunting skeletons he moonlights as a cat historian, and his book co-authored by his tabby cat Baba, A Cat’s Tale: A Journey Through Feline History, was a 2020 Barnes and Noble Book of the Year.