When Prince Don Carlos, the son of the most powerful man in the world, took a bad fall, it was feared that the festering wound on his forehead would bring his short life to an end. It was 1562, and if anyone had the means to save someone from the clutches of death, it was Philip II of Spain, the king of the Empire where the sun never set. He gathered the most eminent doctors and anatomists around his son’s bed, yet none of them were able to find a cure. Since science had failed, the royal confessor resolved, perhaps they should seek help from Heaven.

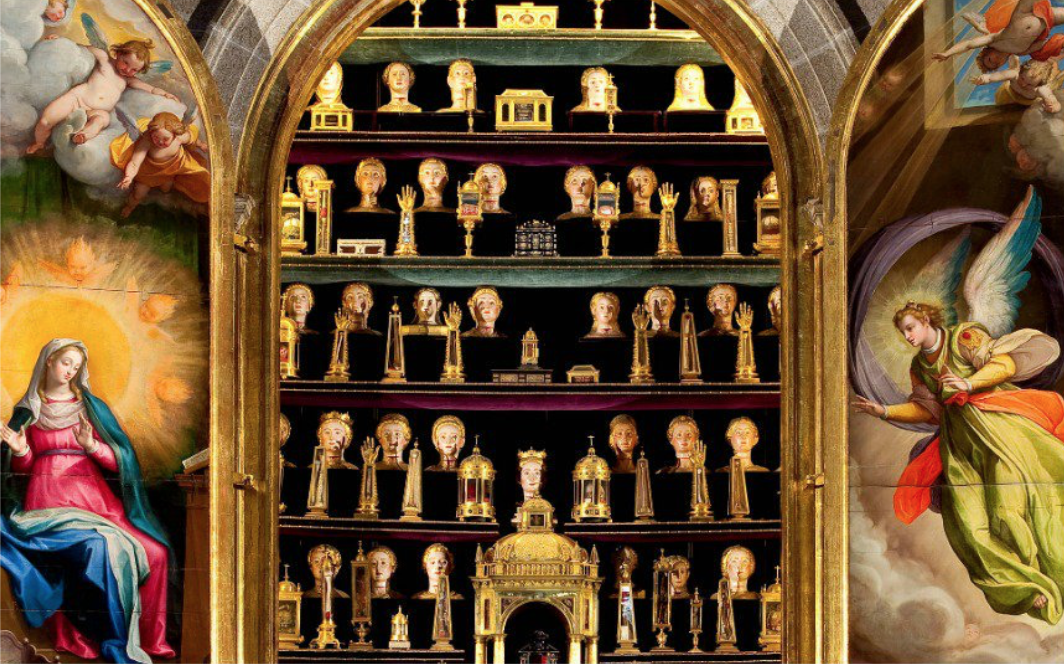

The king was a devout Catholic, known for his “holy greed for relics”: his collection, which he kept close to his bedchambers, included 12 whole skeletons, 144 heads, and thousands of bones from all known saints, except three. However, their alleged healing properties, a deeply-rooted Christian belief, didn’t work on young Don Carlos. Instead, the king’s confessor, Bernardo de Fresneda, suggested they seek the intercession of local miracle-maker Fray Diego de Alcalá. Since he had been dead for a hundred years the friar couldn’t perform a miracle in his living presence, but perhaps his corpse would.

At the orders of the king, Fray Diego’s sarcophagus was opened so his mummified remains could be brought to the prince’s room, where they were ceremoniously laid next to him. Days later, Don Carlos finally woke up. He told his father that he’d dreamed of Diego, who said he would live. His miraculous recovery was attributed to the relics’ sacred power, and the friar was later canonised.

The image of the 18-year-old prince sharing his bed with the shrivelled corpse of a man yanked out of the grave at the king’s orders is nothing short of shocking, but it wouldn’t have been an unusual sight in the court of the Spanish Habsburgs. In 1619, 57 years after the episode of Prince Don Carlos, Philip III, the successor of Philip II, fell gravely ill when he travelled from Portugal to Madrid, and had to be tended in the town of Casarrubios del Monte. As death loomed close, a procession brought from Madrid to his bedside the incorrupt body of Isidore the Labourer, an 11thcentury farmworker known for having performed several miracles in his lifetime, but yet to be a saint. His mummy, also considered miraculous, had been mutilated twice, according to oral tradition: the first time in 1381, when Queen Consort Juana Manuel demanded one arm, but returned it on the spot, since she was suddenly struck “with a paroxysm”; the second time, in the 15thcentury, when a servant of Queen Isabella bit off one of its toes as she pretended to ceremonially kiss its feet. Isidore’s body, lain next to Philip III, allegedly revived the king, and his canonisation, initiated by Philip II, was completed in 1622.

In 1641, when Queen Mariana of Austria went into labor, the bodies of both Diego and Isidore were brought to her chambers as she gave birth to the sickly boy who would become the last of the Spanish Habsburgs, Charles II, known as “The Bewitched”. We now know that his innumerable health problems were the consequence of several generations of inbreeding, however, Charles II believed himself hexed, a concern also shared by his court and subjects. Seeking relief, he became a regular bedfellow of both mummies, and was also the beneficiary of the third mutilation of Isidore’s body, when a locksmith pulled out one of its teeth so the king could keep it under his pillow.

No remedy, heavenly or otherwise, was able to solve the fertility problems of Charles II. His first wife died after ten years of marriage without having produced an heir. His second wife, Maria Anna of Neuburg, was chosen because of the extraordinary fertility that seemed to run in her family: her mother having given birth to twenty-three children. Sadly, this didn’t exempt Maria Anna from being treated for a problem that was more than likely rooted in her husband’s condition. She was subjected to copious blood-letting and aggressive fertility treatments, leaving her so debilitated that the doctors feared for her life, but she recovered after lying next to Isidore’s remains. As a measure of gratitude, she commissioned an urn of silver, where the saint’s body is still stored.

The custom of sharing beds with Isidore’s mummy didn’t fade with the demise of Charles II. The saint’s thaumaturgic powers also protected the following dynasty, that of the Bourbons: Maria Luisa of Savoy, Charles III and his wife, Maria Amalia of Saxony, who all welcomed his body into their royal chambers.

Catholics still venerate relics, and, occasionally, some of them are brought to the beds of the infirm. We find it easier to accept when these relics are fragments of clothing, bones, or even skulls or limbs, but our modern culture has had such little contact with dead bodies that the idea of sharing a bed with a mummy is unimaginable. Did the Habsburgs have to overcome a revulsion towards corpses to lie next to the remains of these saints? Perhaps they did, but instead, regarded it as a privilege they were able to enjoy solely because of their royal status.

The Christian belief in the resurrection of body as well as soul implies that all bodies are sacred, touched by the divine through incarnation and resurrection, so venerating mortal remains is considered natural. Relics which hold the power that the saints had once channelled when they were alive, aren’t merely a symbol of the divine, but an embodiment of it. Lying next to these remains, in their own private rooms, was unattainable for regular people. Yet, for the Habsburgs, this was an act of faith, a powerful reminder of both their own mortality and the hope for an afterlife, as well as an expression of their great power and their privilege.