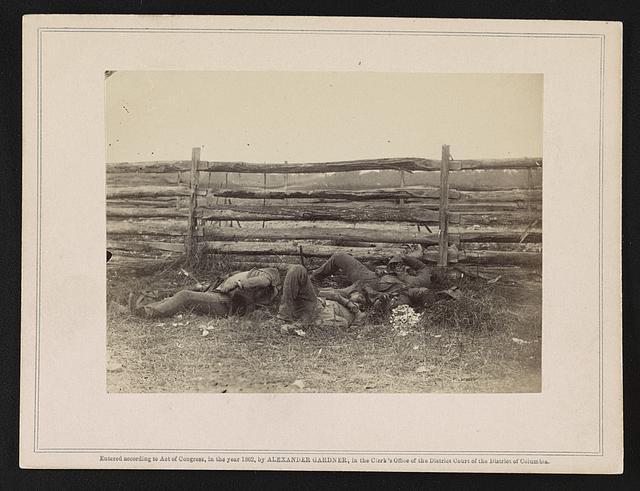

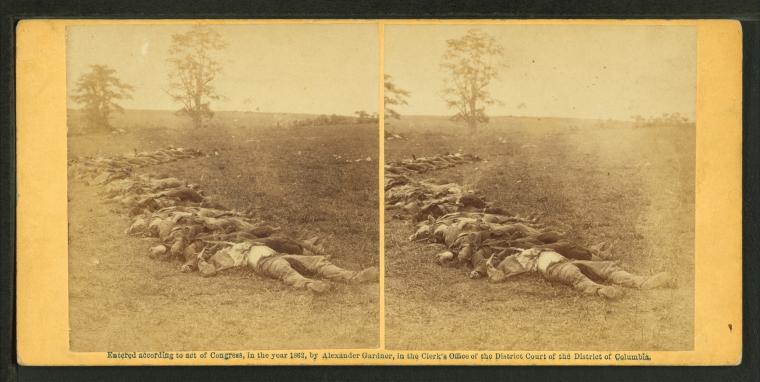

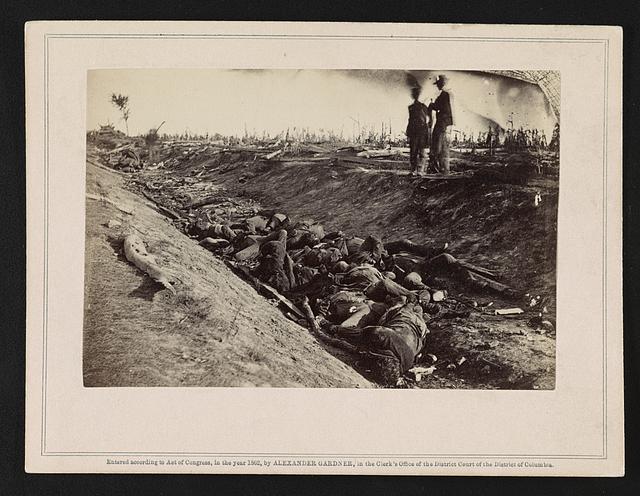

In October of 1862, photographer Matthew Brady’s gallery at Broadway and Tenth Street in New York City announced a new display. “The Dead of Antietam,” read a simple sign over the door. The Battle of Antietam, still considered the single bloodiest day in American history with over 22,000 killed or wounded, was just weeks earlier on September 17 near Sharpsburg, Maryland. The crowds which queued for hours to enter Brady’s gallery witnessed something unprecedented: photographs of corpses on the battlefield.

Both Union and Confederate soldiers were tangled together in otherwise bucolic landscapes, with bodies awaiting burial lined up unceremoniously on the grass. The photographs were detailed enough to make out faces, their features bloated but distinct, which visitors quietly examined with shock and fascination. A horse crumpled on the ground regarded the viewers with a vacant expression; a peaceful white church was pocked by bullet holes. In an eloquent article in the October 20, 1862 New York Times, one writer contrasted these images to the tallies of the dead printed each day in the newspaper: “Each of these little names that the printer struck off so lightly last night, whistling over his work, and that we speak with a clip of the tongue, represents a bleeding, mangled corpse. … Mr. Brady has done something to bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war. If he has not brought bodies and laid them in our dooryards and along the streets, he has done something very like it.”

Although Brady’s name was stamped on all the glass plate prints and stereographs, it was actually his employee Alexander Gardner with the assistance of James Gibson who had lugged the cumbersome photography equipment and developing chemicals to the battlefield. “Gardner and Gibson had taken seventy views in the smoky aftermath of Antietam, the first time photographers had been on the scene before the burial details had performed their somber services,” wrote Jennifer Armstrong in Photo by Brady: A Picture of the Civil War.

Physician and poet Oliver Wendell Holmes, who searched for his son at Antietam following the battle, described their impact: “Many people would not look at this series … It was so nearly like visiting the battle-field to look over these views, that all the emotions excited by the actual sight of the stained and sordid scene, strewed with rags and wrecks, came back to us, and we buried them in the recesses of our cabinets as we would have buried the mutilated remains of the dead they too vividly represented.”

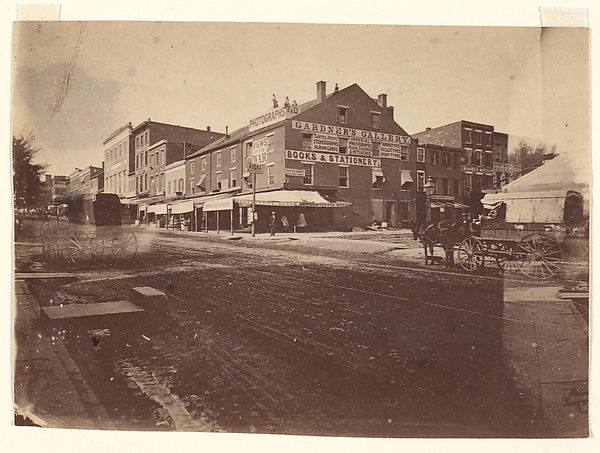

Gardner’s work still influences our perception of the Civil War, the grisly photographs maintaining their quiet savagery, and undercurrent of voyeurism. The images were such a success that Gardner, a Scottish immigrant, left Brady’s team and set up his own studio and gallery at 7th and D streets in Washington, DC. An 1864 photograph of Gardner’s Gallery captures it covered with signs advertising ambrotypes, cartes de visite, stereographs, album cards and, in the biggest letters of all, “VIEWS OF WAR.”

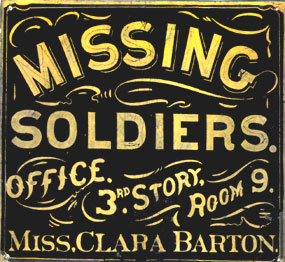

It’s near that intersection that the Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Office Museum is recreating the original display of Gardner’s photographs. (The nurse and Red Cross founder Clara Barton was herself at the Battle of Antietam, working non-stop even after a stray bullet shot through her sleeve and killed a soldier she was treating.) “Gardner’s gallery was located in the same block of 7th Street N.W. as was Clara Barton’s office,” said Bob Kozak, who organized the exhibition. “In some ways, the photos have come home.”

It’s near that intersection that the Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Office Museum is recreating the original display of Gardner’s photographs. (The nurse and Red Cross founder Clara Barton was herself at the Battle of Antietam, working non-stop even after a stray bullet shot through her sleeve and killed a soldier she was treating.) “Gardner’s gallery was located in the same block of 7th Street N.W. as was Clara Barton’s office,” said Bob Kozak, who organized the exhibition. “In some ways, the photos have come home.”

Called War on Our Doorsteps, the show is at the Missing Soldiers Office Museum through November 3. It was previously at the Antietam National Battlefield and the National Museum of Civil War Medicine in Frederick, Maryland. “After some research we discovered that no one in 150 years had ever restaged the exhibit and explored its impact,” Kozak said. “The Maryland government gave us a grant, which we matched, and we were off to the races. Many hours of research and reading 1862-63 era columns and articles, as well as comparing the photos to contemporary woodcuts based on the photos, showed us how several levels of censorship emerged.”

Newspapers in the 19th century did not have the technological capability to print photographs, and these woodcuts softened Gardner’s photographs, eliminating the gore so the soldiers appeared more asleep than dead. Much of the images’ power was in their suggestion that these anonymous individuals, left to rot in the open air, could be anyone, a son, a brother, a friend. There was some effort in the captions to distinguish Union from Confederate soldiers; the photographs themselves had no distinctions between sides.

Alexander Gardner’s 1865-66 Photographic Sketch Book of the War, featured a photograph by Timothy H. O’Sullivan from July 1863, titled “A Harvest of Death,” showing the body-strewn battlefield of Gettysburg. Gardner wrote that photography like this “shows the blank horror and reality of war, in opposition to its pageantry. Here are the dreadful details! Let them aid in preventing such another calamity falling upon the nation.”

Did these photographs change perceptions of the human cost of war? The influence of the Civil War on photography is well-documented, and Gardner’s photographs are significant as some of the first acts of photojournalism. (However they should not be taken as objective truth; Gardner infamously posed a dead soldier at Gettysburg to get a better composition.) Yet 150 years later, we remain uneasy about the corpses of conflict. Only in 2009 was a 1991 ban on photographing the coffins of American soldiers lifted. Before that a photograph by a government contractor named Tami Silicio of 20 coffins traveling from Kuwait to Delaware was published on the April 18, 2004 front page of the New York Times, sparking debate on censorship and privacy. Even with the present ubiquity of photography, the scenes we see of war rarely have that aching silence of Gardner’s Antietam images, their depictions of death still radical in their stillness.