“Place the body on a lounge or sofa, have the friends dress the head and shoulders as near as in life as possible, then politely request them to leave the room to you and aids, that you may not feel the embarrassment incumbent should they witness some little mishap liable to befall the occasion.[1]” Since the inception of photography in the first half of the 19th century, photographing the dead has been an accepted memorial practice. Although it is often cast aside or scoffed at as some kind of bizarre and morbid happening, postmortem photographs represent a particular part of mourning in this era. These beautiful and moving images depict the last moment that a family would be able to grieve with their deceased loved one present. Beyond this, postmortem photographs speak to the mourning and funeral norms of the times.

The memorial, or postmortem photograph, has been around nearly as long as photography itself. The first photograph of a deceased person was a daguerreotype. This antiquated photographic process is understood as one of the first types of photography, which renders a ghostly image on a metallic, silvery surface. Developed in 1839, the first postmortem photograph was taken in 1841.[2] This timeline shows that photography was actually filling a kind of memorial void that other forms, such as paintings, could not. Most importantly, taking a photograph of your dead loved one was simply faster than other mediums, and would eventually become more affordable as well. It was also possible that these photographs were the only images captured of this person, as photography was still a recent invention that was not always affordable or available. This final image may also be the only documentation of this person in their entire life.

The practice of capturing a final “likeness” had even become part of the photographer’s professional repertoire. In an 1869 edition of the Philadelphia Photographer, a trade journal offering a vast catalog of information and contacts, a photographer describes this experience. J.M. Houghton begins, “The other day I was called upon to make a negative of a corpse,” who then goes on to discuss the moving of the body closer to a window, in order to make use of natural light: “I selected a room where the sunlight could be admitted, and placed the subject near the window, and a white reflecting screen on the shade side of the face.”[3] This standard practice, photographing the dead, was even worth discussing amongst professionals. Since the body would be moved by the photographer and was obviously less mobile, there were certain tips and tricks that made image-making much more efficient.

The practice of capturing a final “likeness” had even become part of the photographer’s professional repertoire. In an 1869 edition of the Philadelphia Photographer, a trade journal offering a vast catalog of information and contacts, a photographer describes this experience. J.M. Houghton begins, “The other day I was called upon to make a negative of a corpse,” who then goes on to discuss the moving of the body closer to a window, in order to make use of natural light: “I selected a room where the sunlight could be admitted, and placed the subject near the window, and a white reflecting screen on the shade side of the face.”[3] This standard practice, photographing the dead, was even worth discussing amongst professionals. Since the body would be moved by the photographer and was obviously less mobile, there were certain tips and tricks that made image-making much more efficient.

Charlie E. Orr, a photographer from Sandwich, Illinois, wrote into the Philadelphia Photographer in January of 1873, and wrote a brief article to “afford assistance to some photographer of less experience, to whom it might befall the unpleasant duty to take the picture of a corpse.”[4] Orr goes on to explain:

Place you camera in front of the body at the foot of the lounge, get your plate ready, and then comes the most important part of the operation (opening the eyes); this you can effect handily by using the handle of a teaspoon; put the lower lids down, they will stay; but the upper lids must be pushed far enough up, so that they will stay open to about the natural width, turn the eyeball round to its proper place, and you have the face nearly as natural as life. Proper retouching should remove the blank expression and stare of the eyes.

Photographing the dead proved to have some interesting challenging, but unlike the living, the deceased sitter could not move. With long exposure times, the dead were the ideal photographic subject.

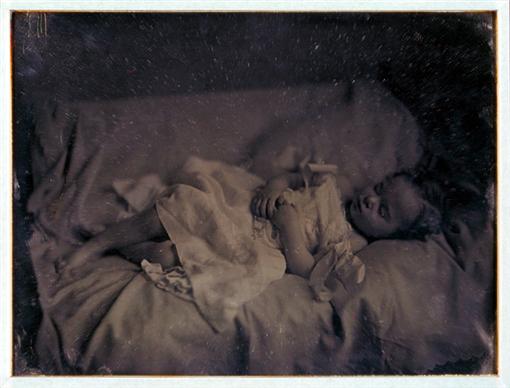

The composition and appearance of postmortem photographs changed throughout the 19th century. For example, postmortem photographs taken prior to the 1860s depict death as if it had just happened; many images from this era share similar poses and details. Most of these photographs concentrate on just the face or head, laid out on furniture in the home or placed on a bed or in a child’s buggy.[1] With many photographs showing the body laid out, sometimes on a bed, the viewer is invited to understand the death as a visual representation of the “last sleep.[2]” These photographs were not intended to dupe the viewer into assuming the deceased was still alive but rather they would be posed in such a way that to recall or depict the subject as if they were just asleep, thus softening the sad reality that they had died. In this way, the postmortem photograph represents the body at peace.

Around the turn of the mid 19th century, postmortem photographs also demonstrate shifting cultural ideas. At this point, many postmortem photographs depicted children. Throughout the Industrial Revolution, children were valued laborers. It was not until 1836 that Massachusetts became the first state to sign child labor legislation into law; it required that children under the age of fifteen attend school for at least three months out of the year[3]. This law also speaks to the fairly recent inception of systematized formal education for children. With newly enacted child labor laws in conjunction with the increasing value placed on formal education, children began to occupy a different role within the family. They became understood not only as wage earners, but as young, evolving humans who should be nurtured and supported.[4]

Around the turn of the mid 19th century, postmortem photographs also demonstrate shifting cultural ideas. At this point, many postmortem photographs depicted children. Throughout the Industrial Revolution, children were valued laborers. It was not until 1836 that Massachusetts became the first state to sign child labor legislation into law; it required that children under the age of fifteen attend school for at least three months out of the year[3]. This law also speaks to the fairly recent inception of systematized formal education for children. With newly enacted child labor laws in conjunction with the increasing value placed on formal education, children began to occupy a different role within the family. They became understood not only as wage earners, but as young, evolving humans who should be nurtured and supported.[4]

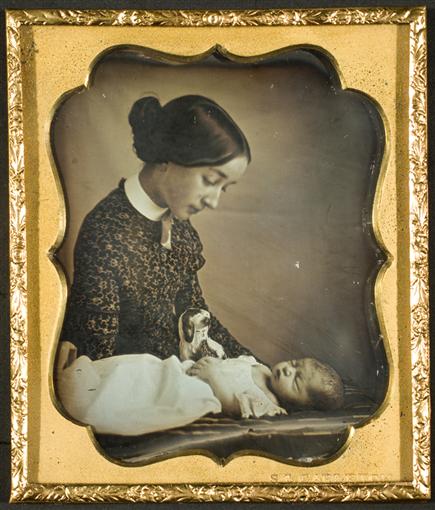

With this changing role, postmortem photographs of children also began to change. For example, this photograph from 1860 depicts a recently deceased young girl, who is sitting on the lap of her mourning mother.[5] The mother’s face is straight and unwavering, looking directly at the camera. She holds her daughters hand for the last time, as her small body is cradled by her mothers. Her mother is clearly in mourning. Many photographs of this decade began to include the presence of loved ones, either around the body of the recently deceased, or embracing or touching them in some way.

With this changing role, postmortem photographs of children also began to change. For example, this photograph from 1860 depicts a recently deceased young girl, who is sitting on the lap of her mourning mother.[5] The mother’s face is straight and unwavering, looking directly at the camera. She holds her daughters hand for the last time, as her small body is cradled by her mothers. Her mother is clearly in mourning. Many photographs of this decade began to include the presence of loved ones, either around the body of the recently deceased, or embracing or touching them in some way.

At this time, many photographs of the dead became more elaborate or indicative of what that person had been like in life. Some children would be photographed with a favorite toy or blanket, depicting an image that allows the viewer to imagine what they had been like in life.[6] Other photographs would show a body outstretched in their final resting place, which may be an elaborate coffin or even a casket.

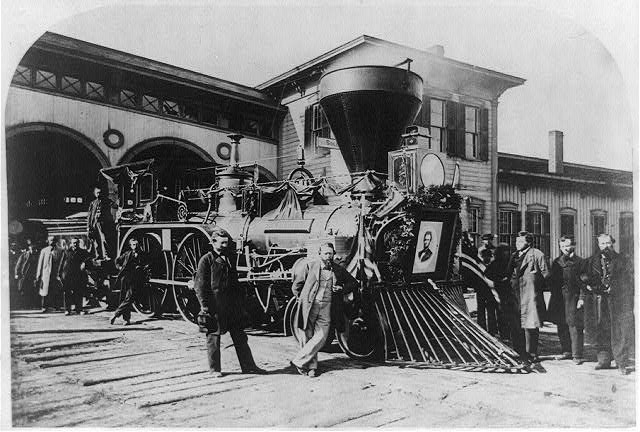

By the end of the 19th century and the start of the 20th century, funerary patterns began to shift. Embalming was first introduced on a national level and seen widely after President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination on April 15, 1865. He laid in state for three days and was viewed by over 25,000 mourners before being sent to his home of Springfield, Illinois: his body traveled over 1,700 miles from Washington D.C. to his hometown[1], where he was to be buried, making many stops along the way.[2] Embalming required professional intervention in the funeral, which led to the inception of the funeral director.

By the end of the 19th century and the start of the 20th century, funerary patterns began to shift. Embalming was first introduced on a national level and seen widely after President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination on April 15, 1865. He laid in state for three days and was viewed by over 25,000 mourners before being sent to his home of Springfield, Illinois: his body traveled over 1,700 miles from Washington D.C. to his hometown[1], where he was to be buried, making many stops along the way.[2] Embalming required professional intervention in the funeral, which led to the inception of the funeral director.

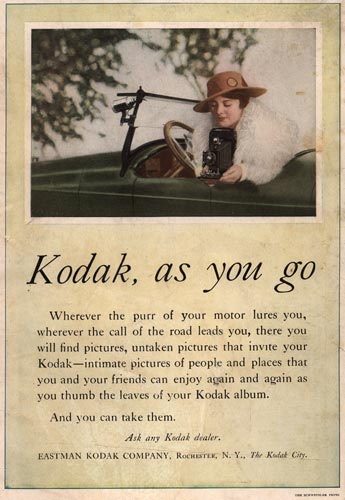

Photography was also becoming a daily part of American life. Photographic technology became easier to use, and the supplies became more accessible. Companies like Kodak began to advertise heavily, creating campaigns that would heavily influence how photographs were taken up in culture.[3] Photos were now taken at holidays and on vacation, as well in day to day activities. When photos were able to depict the joys of life, there was less emphasis on photographing the dead. There was simply other ways to show someones life other than their last moments.

Photography was also becoming a daily part of American life. Photographic technology became easier to use, and the supplies became more accessible. Companies like Kodak began to advertise heavily, creating campaigns that would heavily influence how photographs were taken up in culture.[3] Photos were now taken at holidays and on vacation, as well in day to day activities. When photos were able to depict the joys of life, there was less emphasis on photographing the dead. There was simply other ways to show someones life other than their last moments.

Postmortem photographs became less popular in the first quarter of the 20th century. Infant mortality dropped due to a variety of important medical developments, and childhood illnesses began to be better managed. Photography captured the living, and less of the dead. Shifting away from Victorian ideals surrounding death, dying became medicalized and professionalized.

Although postmortem photography did not simply stop, it lost the popularity it once had many years prior. Photographing the dead still happens today, but not to the extent that it once had. These kinds of photographs end up on ebay and in thrift stores, often separated from the families that they once belonged to. For many that do photograph at funerals, digital photos end up on computers or phones, ready to be deleted when the longing to look has passed. What has not changed, however, is our desire to look at photos of those we loved, whether they are dead or alive.

[1] IMAGE: http://www.loc.gov/item/2009633711/

[2] Drew Gilpin Faust. This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War. (New York: Random House, 2008), 157.

[3] IMAGE: https://tpwd.texas.gov/spdest/findadest/historic_sites/ccc/new_deal_texas_html/media/images/2/kodak_ad_345x500.jpg

[1] Jay Ruby. Secure the Shadow: Death and Photography in America. (Boston: MIT Press, 1995), 19.

[2] IMAGE: http://licensing.eastmanhouse.org/GEH/C.aspx?VP3=ViewBox_VPage&VBID=2744WNB9Z071&IT=ZoomImage01_VForm&IID=2F3XC5UQJT1&PN=33&CT=Search

[3] Child Labor Public Education Project. “Child Labor in U.S. History.” University of Iowa Labor Center and Center for Human Rights. http://www.continuetolearn.uiowa.edu/laborctr/child_labor/

[4] IMAGE: http://www.loc.gov/resource/ppmsca.34974/

[5] IMAGE: http://www.loc.gov/resource/ppmsca.11042/

[6] IMAGE: http://licensing.eastmanhouse.org/GEH/C.aspx?VP3=ViewBox_VPage&VBID=2744WNB9ZJX2&IT=ZoomImage01_VForm&IID=2F3XC58Z2RZA&PN=1&CT=Search

[1] Philadelphia Photographer. 1875 volume 11. Page 27.

[2] John Hannavy ed. Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography. (New York: Routledge, 2008), s.v. “postmortem photography.”

[3] Philadelphia Photographer. 1869 volume 6. Page 241.

[4] Philadelphia Photographer. 1873 volume 10. Page 200.