Pixar’s new film Coco, tells the story of the Rivera family against the lavish backdrop of Dia de Muertos (Day of the Dead), a sacred and ancient annual tradition originally observed by indigenous people throughout Latin America, in which the souls of the deceased are able to return for a reunion with their living family members. Here, we’ll delve a little deeper into some of the traditional folklore and rituals that are depicted throughout the film.

As Coco opens, audiences are immediately introduced to several key elements of Dia de Muertos; candles, copal, and cempasuchil.

Candlelight is used to attract and guide the spirits of the dead during Dia de Muertos. In many regions a single white taper is lit for each deceased family member. Tall candles are typically used for adults, while shorter ones are used for children, a reference to their brief lives.

In other areas, candles become a part of the altar itself, like the elaborate display seen here at a cemetery in Tzintzuntzan. Candles lit in the cemeteries are watched over throughout the night to ensure that no flame is ever extinguished.

A fragrant resin derived from a sacred tree, copal is burned on altars and in cemeteries during Dia de Muertos to attract the dead. To this day it is believed that the smoke from burning copal can carry prayers and messages from the living to the energies and spirits that reside in the lands of the dead.

Orangey-gold flowers called cempasuchil, play an important role in Dia de Muertos rituals. It is believed that the spirits of the dead are attracted to the scent of this flower so, altars and graves are often decorated with them. Paths of their petals can be seen leading to a cemetery or into a house to help guide the dead, bridging the way between the worlds of the living and the dead, as seen in the film.

The Mexica cultivated cempasuchil for use in rituals, ceremonies and also as a medicine. Water infused with cempasuchil was used to bathe corpses before burial or cremation, and is often planted on or near graves.

The story of the Rivera family is beautifully retold through panels on colorful tissue paper banners called papel picado. It is believed that Chinese paper cutting art came to Mexico via traders and merchants in the 17th century. Mexicans put their own spin on the art, trading in their scissors for chisels to bring familiar cultural motifs, like birds and skulls, to life.

In the early 20th century artisans in Puebla became renowned for their paper artistry and it was during this time papel picado became popularized. It’s used not only during Dia de Muertos, but at many different celebrations throughout the country.

One of the most endearing characters in Coco is Dante, a xolo dog. Xoloitzcuintli (xolo “sho-low” for short) were a beloved and sacred breed that acted as a guide and companion to the dead. Mexica believed that the journey to the afterlife would take someone four long years after their death. In order to reach Mictlan, the land of the dead, a spirit could only cross a river if they were carried to the other side by a xolo. Once there, they were welcomed by Mictlantecuhtli, the Lord of the Underworld. To mark their arrival in Mictlan the family of the deceased would burn what remained of their belongings, as well as other offerings of gratitude to Mictlantecuhtli.

People were often buried with dog statutes, or their corpses adorned with necklaces that had a dog figure on it. There are several ancient depictions of deceased persons arriving with their xolo to present offerings to Mictlantecuhtli. Artist Frida Kahlo, who also makes an appearance in the film, was frequently photographed with her xolos, and also incorporated them into some of her art.

Coco’s “spirit guides,” which act in a role similar to that of a xolo, are reminiscent of a type of folk art called alebrije. Like the character of Pepita, who is comprised of what seems to be a jaguar, an eagle and a lizard, alebrijes are fantastical, colorful creatures that feature elements of several beasts. If alebrijes look like something out of a fever dream it’s because they are. As the legend goes, in the 1930s Mexican artist Pedro Linares Lopez fell gravely ill and dreamed of these strange creatures who called themselves “alebrijes.” When Lopez recovered he recreated what he saw in paper mache form. Other artisans were inspired and began carving their own alebrijes out of copal wood.

Each year in Mexico City, just before Dia de Muertos, you can catch an incredible parade featuring life size alebrijes!

As seen in the Rivera family home, the ofrenda, a beautifully adorned altar in which photos and offerings comprised of gifts for the visiting spirits are placed, is the heart of Dia de Muertos. Drinks and favorite foods are laid out on the altar, along with things loved ones enjoyed during their lifetime. The ofrenda typically features the most iconic symbol of the festivities, the sugar skull.

In order to understand the significance of the sugar skull and how they came to be, you’ll need a bit of historical context. When Spanish Colonists arrived, they made great efforts to eradicate the indigenous people’s practices of honoring their ancestors, under severe punishment and and torture. In the 1700s the Spanish established laws controlling and abolishing Mexicans’ funerary and mourning practices. The laws issued included the following edict:

“The use of food and private banquets on burial days, during funerary commemorations or on the Days of the Dead is absolutely forbidden and reproved.”

The goal? “So that these abominations can be entirely uprooted.”

We know that Pre-hispanic people had been using a grain called amaranth not only as a main food source, but it was also used in sacred birth and death rituals. Amaranth sculptures of skulls and animals were believed to be offerings to the dead or perhaps to Mictlantecuhtli. The Spaniards outlawed amaranth, in an effort to physically, emotionally and spiritually weaken the people. The punishment for planting it was removal of one’s hands. Some anthropologists believe sugar skulls are tied to the original amaranth sculptures.

By the 1800s wealthy Mexicans were under pressure from the church to provide money, clothing & food to the poor when a family member died, instead of spending money on the funeral itself or a funeral feast. Out of this arose a practice, that is similar to souling or giving out soul cakes to the poor on All Soul’s Night in exchange for praying for the souls of their dead, which the church told them were trapped in purgatory. The sugar skull became a token of funerary charity when people would approach funeral processions and enact a form of ritual begging by asking for “Una calavera,” a skull. It later became a tradition to give calaveras in the form of sugar skulls to children and close friends and family. Sugar skulls are not only the result of oppression, but a testament to the resilience and spirit of Mexicans.

Cloths and baskets are often put out on or near the ofrenda, so that the ancestors have something to carry their gifts back to the land of the dead in. This is given a modern twist in Coco, as we see the spirits passing through a customs area to declare their belongings.

It is here, at the customs area, that Coco first introduces the audience to the idea of the Three Deaths: “In our culture we die three deaths. The first death is when our bodies cease to function, when our eyes no longer hold a presence. The second death is when our bodies are returned to mother earth, and we can longer see it. The third death, the most definitive death, is when there is no one left alive to remember us.” – Via Victor Landa.

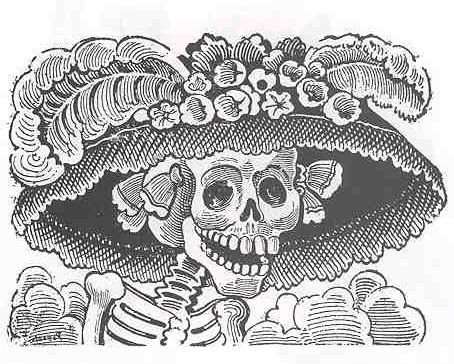

Once Miguel arrives in the land of the dead, he is literally given a hand by a woman that resembles another one of Mexico’s iconic symbols, La Catrina Calavera, which was created by Mexican artist Jose Guadalupe Posada, who frequently used his art to comment on events and politics of the day. La Catrina was a satirical commentary on upper class Mexican women who favored and tried to emulate the culture, fashion and lifestyle of Europeans (white Colonists), over their own.

Once Miguel arrives in the land of the dead, he is literally given a hand by a woman that resembles another one of Mexico’s iconic symbols, La Catrina Calavera, which was created by Mexican artist Jose Guadalupe Posada, who frequently used his art to comment on events and politics of the day. La Catrina was a satirical commentary on upper class Mexican women who favored and tried to emulate the culture, fashion and lifestyle of Europeans (white Colonists), over their own.

The streetcars that carry the dead in Coco, may pay homage to not only Posada’s famous work, but the many dedicated funeral streetcars of Mexico’s yesteryear, which once carried both copses and mourners to their final destination at the cemetery.

When Miguel gets off the streetcar, we see a fiesta in full swing! One important element we get a quick glimpse of is the release of monarch butterflies. In parts of Mexico monarch butterflies arrive every year during the time of Dia de Muertos. Many believe that the souls of the ancestors reside in monarchs and so, their arrival marks the return of the beloved dead.

Pre-hispanic cultures frequently utilized fire in ceremonies and festivals, and so it only makes sense that this ritual element would continue to be adapted in the more modern and spectacular use of fireworks. Fireworks are used in many different festivals, or as is the case in Coco, during celebratory events. Fireworks were also once used during funerals for young children, accompanying the soul of the child up to Heaven.

Music plays a huge role in Coco, and it does in Dia de Muertos too! There are many traditional songs for this time of year – some speak of death and mourning, while others, celebrate our folklore, like La Bruja (The Witch), and La Llorona, which is sung by the character of Mama Imedla during a pivotal scene in Coco. La Llorona, the archetypal weeping women who is lamenting the deaths of her children, is a figure deeply tied to Mexican cultural identity.

During Dia de Muertos, music is integrated into many regional celebrations – from town processionals, to interactive, historical reenactments.

Bands are often hired to play music for the visiting spirits, and sometimes you can find musicians roaming the cemeteries and can hire them to play at the grave of your loved ones.

El Grito, is a type of musical cry or yell used to express emotion, and it is heard over and over again throughout Coco. Confused? (I promise, you know what a grito is, take a listen here). There are different types of gritos used in music, some are cries of pain for centuries of oppression, while others ring with joy and resolution.

The beautiful, hallmark song of Coco, is “Remember Me.” Although the focus here is on our connection to our ancestors, the makers of Coco were also honoring the importance of family, and calling attention to the many families who are separated by borders created by the living; and not just those separating us from the dead.

Remember me

Though I have to say goodbye

Remember me

Don’t let it make you cry

For even if I’m far away I hold you in my heart

Sarah Chavez is the executive director of The Order of the Good Death, co-host of the Death in the Afternoon podcast, and a co-founder of the Collective For Radical Death Studies. As one of the founders of the Death Positive movement, she is passionate about addressing the underlying issues that adversely effect marginalized communities’ experiences of death. Sarah writes and speaks about a variety of subjects including the relationship between food and death, Mexican-American death history, feminist death, and decolonizing death rituals. You can follow her on Twitter .