The choice to go to Belize on vacation wasn’t about any specific lifelong dream of visiting Belize. I was looking for was somewhere totally remote, worried that I had become a wee bit pathologically enslaved by the daily siren song of the Facebook/Twitter/blog/YouTube sphere. That is to say: first world problems.

The place I chose also had to be inexpensive because, “I’m in this for the money”… said no mortician ever. I found a hut on a lagoon in Belize, nine miles away from the nearest town and reachable only by four-wheel drive Land Rover. Internet and electricity were (thankfully) out of the question.

When I arrived, I met the caretaker of the property, a 30-year-old local Belizean man named Luciano. Luciano calls himself a Mestizo — a descendent of the indigenous Mayan people and the invading Spanish.

To give you an idea of the type of man Luciano is, he goes into the Belizean bush (jungle) for days at a time with only his machete and a pack of dogs. He hunts deer, tapir and armadillo, and when he finds one he kills it, flays it on the spot, and eats its heart out of its chest. Not. Even. Kidding.

While sitting in our respective lagoon-side hammocks, Luciano asked me what I did for a living. I told him I worked with the dead, at a crematory. “You burn them — you barbeque people?” Well… sort of.

When someone dies in Belize, the family will often take the body back to the home to lay in wake for a day and night. Then the dead are taken to the church and then finally the cemetery.

There are multiple religions co-existing in Orange Walk (the town Luciano is from): Catholics, Evangelicals, Jehovah’s Witnesses, even Mormons. Luciano was raised Catholic but has since disavowed religion. He prefers to believe in the power of nature instead, although he does believe the Ark of the Covenant is waiting for him somewhere in the desert to grant him eternal life. He also believes he once turned into a fish. Luciano is an interesting guy.

When someone died in their town, Luciano’s grandfather was the one they would call to prepare the body. If he arrived and the body was in full rigor mortis, it would naturally be difficult to dress and bathe the corpse. According to Luciano, this was what his grandfather would do:

You just has to talk to the body, you know?

You has to make sure no one in the room, just look the body in the eye and say, “Look, you want to look good in heaven? I can’t dress you if you want to be hard.”

Then you rub a little rum on him and he’ll loosen up. Just talk to him though. Is that what you do at your job? Just talk to him?

If you talk to the body, it will break out of rigor mortis and allow you to dress it. At the wake, you can talk to the body again, this time to ask it for favors. It’s a shame I haven’t been asking my corpses for favors all these years — I might be a wealthy woman.

The last step in Belizean body prep is to flip the entire corpse on its stomach and push the decomposition gas and purge out. Like burping your corpse baby. This one might actually be a genius technique. Purge anticipation. Burp the corpse before it burps on you.

Modern life has come to Belize in the form of autopsies at the hospitals, often whether the family wants it or not. Luciano’s grandmother did not want to be cut open, no matter what. “That’s why we thieved her body from the hospital,” Luciano told me. “Wait, what?” Yes, I had heard correctly, they stole her body from the hospital. Just wrapped it in a sheet and took it. “What were they going to do?” Luciano asked me. They played Mexican ranchero music at his grandmother’s wake (it was her favorite) and provided buckets of rum to the guests (rum is used for more than loosening up the corpse, it seems).

When he dies, Luciano would like to be buried in a hole with leaves covering all sides and an animal skin over his body. He plans on designing it himself. He explained that his friends “talk about it all the time, saying ‘hey, what you want when you die?’ Don’t people say that where you come from?” It was hard to explain that, no, for the most part they really don’t.

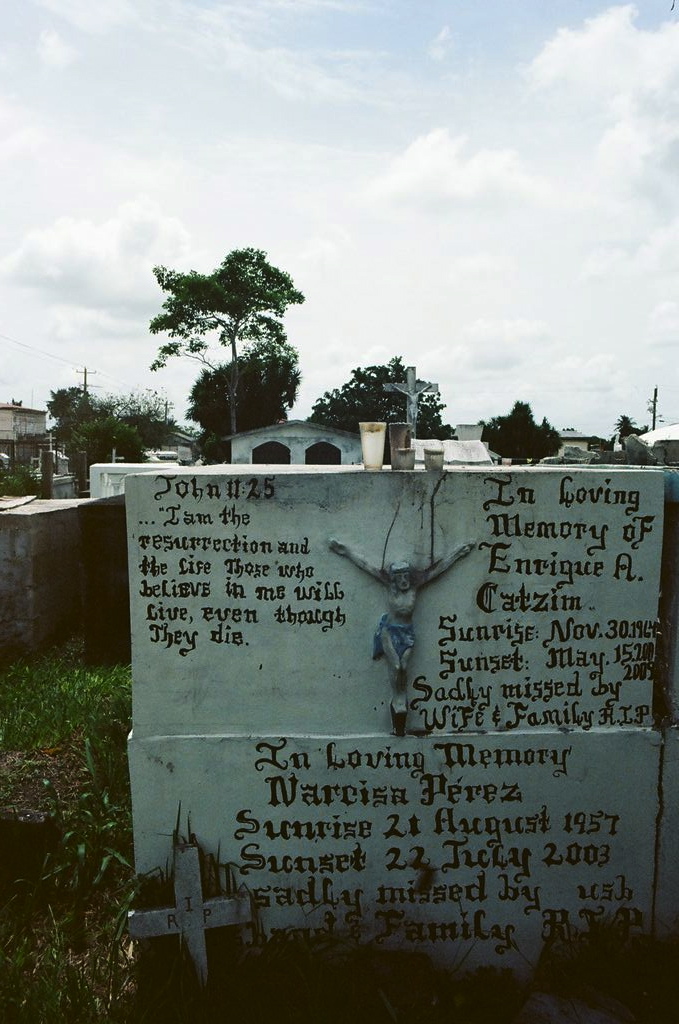

One of my last days in Belize, Luciano took me to the graveyard where his grandparents — who raised him — are both buried. Back in the far corner, under a tree, their caskets lie on top of each other in a cement-covered grave. “My grandmother, she didn’t want this, she wanted dust to dust but, you know.” Luciano lovingly swept the leaves from the top of the grave anyway.