In recent years, Day of the Dead – Dia de Muertos, has become increasingly popular. After all, who wouldn’t be enamored with colorful sugar skulls and smiling skeletons – but what do you REALLY know about the history and meaning behind this sacred practice? Not to worry, I’ve got you covered, in this primer on day of the dead observances.

History

First, let’s delve a little into Mexico’s history. Pre-Hispanic Mexicans possessed extremely complex ideas and practices surrounding death and the dead. These are especially evident as you begin to explore their mythology and creation stories. Many of Mexico’s indigenous peoples observed a month long “Little Feast of the Dead,” involving ritual offerings to the dead, the God of Death and feasting.

Much has been written regarding the horrors of the Spanish conquest of Mexico. What we can extract from this period is the incredible tenacity Mexicans exhibited when it came to maintaining their death rituals and relationship with the dead. Although the church gave the directive to eradicate their “pagan” practices of honoring their ancestors – under severe punishment and torture – they continued. In result, the Spanish established mandatory burial in church graveyards, created laws controlling and abolishing funerary and mourning practices, created a grave tax and in the late 1700s, issued a series of laws that included the following edict:

“The use of food and private banquets on burial days, during funerary commemorations or on the Days of the Dead is absolutely forbidden and reproved.”

Their goal?

“So that these abominations can be entirely uprooted.”

With this constant siege from outside sources specifically targeting the Mexican’s relationship with death; it is evident that this was something of immense importance to them; that defined them and stirred their hearts. For centuries Mexico has fought to maintain and cultivate their unique and intimate relationship with death.

Modern Muertos

Modern Dia de Muertos is a period of days when it is believed that the souls of the dead return to visit the living. It is really like a family reunion.

The key elements of the celebration include cemetery vigils, the erection of home altars, the preparation of special sweets, the presentation of flowers, candles and food to the dead and the performance of ritualized begging.

Symbols and Icons

By the 1800s the wealthy were under pressure from the church to provide money, clothing and food to the poor when a family member died. It is in this context that the term, “una calavera,” a skull, was first used to signify funerary charity. The poor would approach funeral processions asking for “una calavera.” With regard to the calavera as donation, it is the poor who receive the contribution, as they become the symbolic surrogates of the souls in purgatory. Now, we give gifts of calaveras in the form of sugar skulls to children, assorted dependents and close friends.

By the 1800s the wealthy were under pressure from the church to provide money, clothing and food to the poor when a family member died. It is in this context that the term, “una calavera,” a skull, was first used to signify funerary charity. The poor would approach funeral processions asking for “una calavera.” With regard to the calavera as donation, it is the poor who receive the contribution, as they become the symbolic surrogates of the souls in purgatory. Now, we give gifts of calaveras in the form of sugar skulls to children, assorted dependents and close friends.

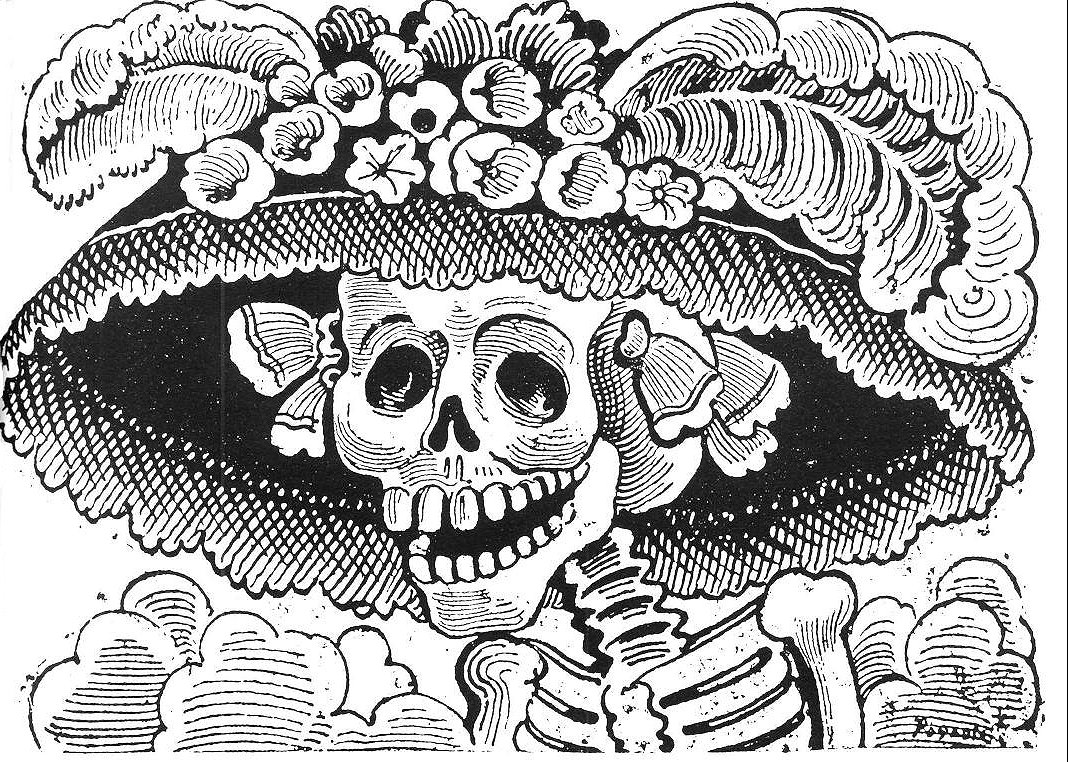

The other image most associated with Dia de Muertos emerged just prior to the beginning of the Revolutionary period in 1910. Here, the image that would arguably define Mexican identity emerged, The Catrina.

The other image most associated with Dia de Muertos emerged just prior to the beginning of the Revolutionary period in 1910. Here, the image that would arguably define Mexican identity emerged, The Catrina.

José Guadalupe Posada was a Mexican artist who was known for his political art, which frequently satirized the upper class. His iconic etchings of skeletons dressed in upper class finery were intended as a satirical portrait of those Mexican natives who, Posada and many others felt were aspiring to adopt European aristocratic traditions in the pre-revolutionary era. This attitude of casting aside one’s culture, after centuries of incredible efforts to preserve it, was infuriating to many.

Altars and Offrendas

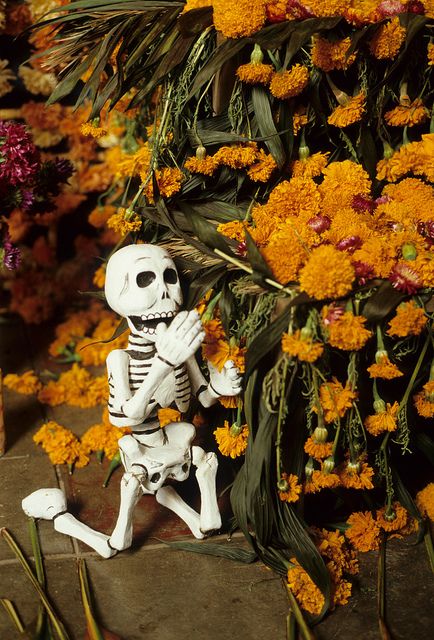

Altars are made and decorated to display the offrendas – the offerings or gifts to the dead. These can be as simple as a table decorated with a few key items, to elaborate multi-tiered altars constructed by special builders.

Common gifts are clothing, food, toys, personal objects and photographs. Anything the person enjoyed while living, we give to them in death.

Golden-orange flowers, cempasuchil play an important role, as the dead are able to follow their scent. Copal incense is also used in the same manner. Flowers are placed on altars and graves in abundance. Sometimes paths of their petals can be seen leading to a cemetery or into a house to help the dead find their way.

Feast

In the 1600s a friar secretly followed some Indians into a huaca, a cave where they interred their dead. There, the friar confronted them, stating how foolish they were to offer all this food to the dead, and asked the Indian Lord why they did it. He answered:

“I know father, that the dead do not eat the meat, nor the bones, instead they place themselves above the food and suck out all its virtues and the substance that they need and leave behind what they don’t need. And if this is not so, why do you allow the Spaniards to place bread, wine and goats on graves in the churches?” **

Pan de muerto, bread of the dead, is made in the shape of a little grave mound with bones or made to look like a corpse. You can find pan de muerto everywhere, both inside and outside the cemeteries, in every panderia and even at Starbucks.

After the souls depart, the food like tamales, candies in the shape of coffins, skulls and skeletons are enjoyed by friends and family. Root vegetables, carrots and jicama are eaten around this time as it is believed that these things which grew under the ground were nourished by the corpses and this is another way we can be closer to the dead.

On the afternoon of October 31st to November 1st, it is time to receive Los Angelitos – spirits of the children who have died. When the spirits of the children arrive, we imagine it as though they are coming out of school, happy and excited to meet their loved ones.

The candles and incense is lit on the altars and people open the doors or go outside to receive them. Everyone sits near the altar and keeps the spirits company.

The following afternoon of November 1st, it is time for the adults to come and the same rituals are repeated throughout November 2nd. This is now a time for many to go to the cemetery to visit loved ones there.

Outside the cemeteries, there are huge markets selling various flower arrangements, food and toys. Inside, cemeteries are crowded and lively. Families carrying buckets of water up tall ladders to wash a grave, food vendors selling ice cream, children playing tag among the headstones or playing with toys right on top of a tomb. Family pets are brought to visit, there are strolling musicians to serenade the dead, families having picnics and laughing – the love and joy shared with the dead during these days is a poignant example of a culture that has cultivated a positive relationship with death.

Sarah Chavez is the executive director of the Order, a museum curator and historian. As a Chicana she often writes and lectures about the inspiring, positive and often complex ways her culture engages with death and the dead.

**English translation quoted from Claudio Lomnitz, Death and the Idea of Mexico, 2008

Manuel Aguilar-Moreno, Handbook to Life in the Aztec World, 2007

Hugh Thomas, Conquest: Cortes, Montezuma, and the Fall of Old Mexico, 1995

Elizabeth Carmichael and Chloe Sayer, The Skeleton At The Feast, 1991