What is COVID-19? For Bill Gates, it is the ‘first modern pandemic’; for UN Secretary General António Guterres, the virus is “the greatest test since World War Two;” and for news outlets, an ‘unprecedented moment’. Yet, as a gay man, I cannot stop thinking of another devastating pandemic that swept the world in the 1980s and 1990s, one that destroyed communities and transformed intimacy, that still kills almost a million people every year: AIDS.

Is it Only Gays that Remember?: The AIDS Crisis and COVID-19

“COVID-19 and AIDS: NYC Gays See Parallels, Contrasts” was the headline that ran on U.S. News on April, 11 2020. Reading this, researcher Jaime García-Iglesias’ immediate reaction was to wonder: was it only gays who remembered AIDS? How could the population at large not remember a crisis that was so devastating? In his first article for The Order, Jamie will try to answer the questions: who remembers, and equally important, who gets to be remembered?

US News, April, 11 2020

“COVID-19 and AIDS: NYC Gays See Parallels, Contrasts” was the headline that ran on U.S. News on April, 11 2020. Reading this, my immediate reaction was to wonder: was it only gays who remembered AIDS? How could the population at large not remember a crisis that was so devastating? That is the question I will try to answer: who remembers, and equally important, who gets to be remembered?

It’s a hot summer day in June of 1981, Kim Carnes’ ‘Bette Davies Eyes’ is at the top of the charts, and the CDC has just published a note saying that five healthy, young men have died from an unusual type of pneumonia in Los Angeles. It would be two more years before scientists would establish that AIDS was caused HIV (human-immunodeficiency virus). By then, almost 200,000 people had contracted it, and many had died.

The AIDS crisis spans between 1981 and 1996, the same year the first effective medication became available; it was a time that was marked by the rapid spread of HIV and death. In 1995, the NYT reported that AIDS was “the leading killer of Americans from 25 to 44”.

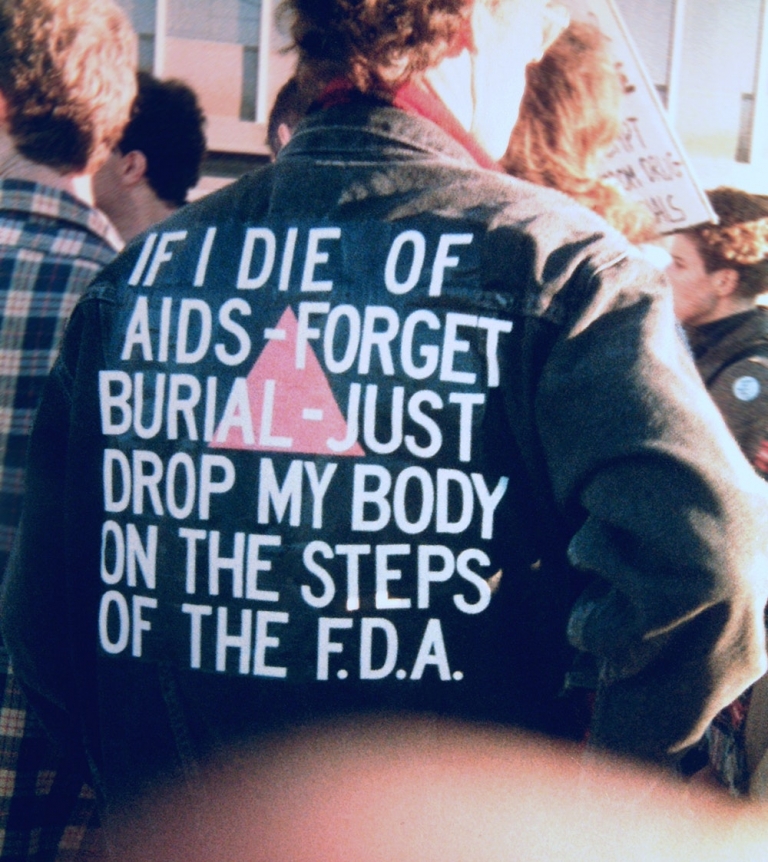

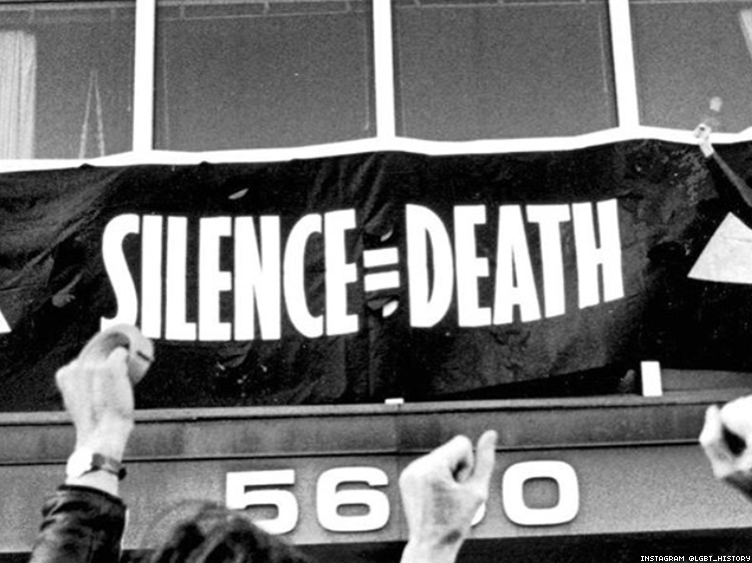

The early association between HIV and gay men (as well as intravenous drug users and immigrants) explains why the Reagan administration refused to act on the unfolding tragedy. Reagan’s Press Secretary, Larry Speakes, laughed in public about AIDS, calling it a ‘gay plague,’ and it would take four long years for the President to even mention AIDS publicly, in 1985. Both the silence and lack of funding from this administration spoke volumes about the prevalent homophobia that existed in society: as well as among the doctors, undertakers and countless others who refused to provide care for those with the virus.

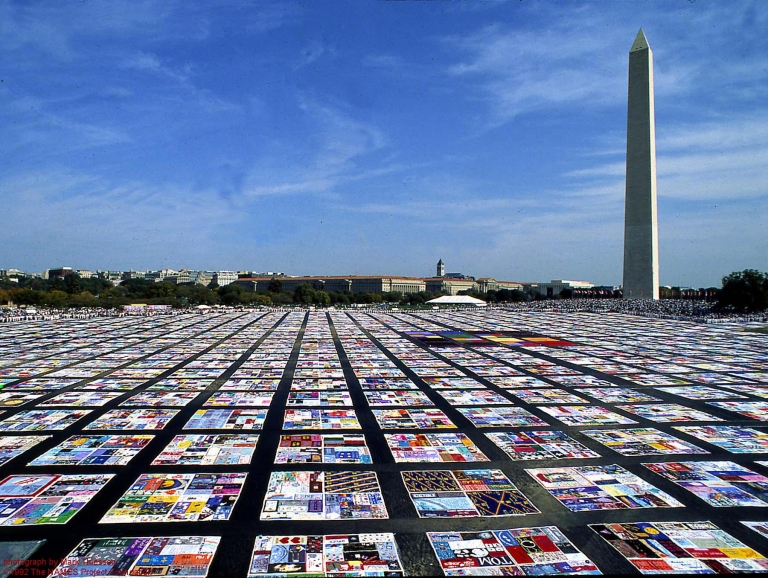

By 1990, twice as many people had died from AIDS in the U.S. than had died in the Vietnam war. Yet there is no big, black wave remembering them, no state-sponsored cemetery. The only large-scale monument to the AIDS crisis is the NAMES AIDS Quilt: a quilt composed of 50,000 panels that people had sewn together to remember a loved one who had died from AIDS. This is a painful reminder of how it was left to activists and victims to make sure that AIDS deaths were remembered.

AIDS quilt in front of the Washington Monument

Sarah Schulman, an American writer and AIDS historian, explains that “the disallowed grief of twenty years of AIDS deaths was replaced by ritualized and institutionalized mourning of the acceptable dead. In this way, 9/11 is the gentrification of AIDS. The replacement of deaths that don’t matter with deaths that do.” That is, as the AIDS crisis slowly came to its end for white communities following the advent of effective medication in 1996, the time was right for reckoning and grief, for the communities most affected to mourn their dead, and for those in positions of power to be held accountable for their homophobia and inaction which resulted in lack of care, support, and endless unnecessary death and suffering. And yet, in 2001, politicians took hold of 9/11 to develop of a sense of national unity in the face of tragedy that precluded any of that from happening.

It can be said that the U.S. national consciousness of AIDS deaths was gentrified: framed as the deaths of gay men, drug users, and others, who were forgotten to make way for the deaths of those deemed more “respectable.”

It can be difficult to understand just how much of a tragedy the AIDS crisis was, especially for those of us who did not live through it. During my research, I interviewed Josh, a 54-year-old man from Chicago, who told me about his experiences of the AIDS crisis:

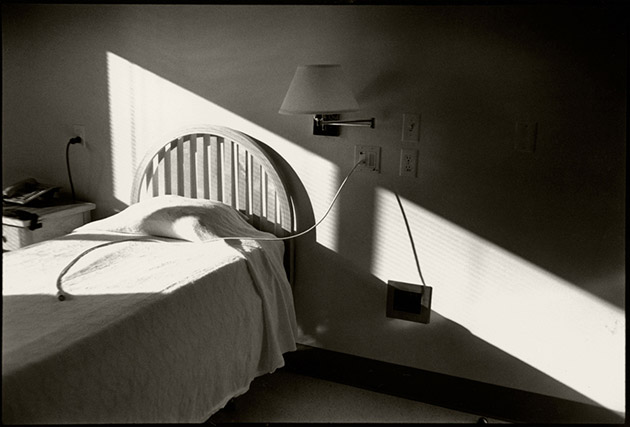

“It was almost ‘84, I was 18, and I got a boyfriend. About a year and two months later, he was dead. By ‘85, all of his friends started to get AIDS. So for two years, up until 1987, my life was people dying in my arms. I was taking care of them, but the problem was that there was nothing to do, they were just dying. Some of them had a horrible death, most died in my apartment. All I remember from those years, it was so weird, it was taking care, taking care, and that push, push, push forward. I remember when Shawn died in 1987. He was the last one because all the others had already died.”

Saul Bromberger & Brandy Hoover

A resident’s room the day of his death from AIDS at the Bailey-Boushay House, an HIV/AIDS care center in Seattle.

Today, Schulman writes how AIDS “was a phenomenon so broad and vast as to permanently transform the experience of being a person in the world” and philosopher Paul B. Preciado argues that COVID-19 poses this question: “Under what conditions, and in which way would life be worth living?” There is an eerie similarity between these two reflections, a sense that COVID-19 is not, after all, that unprecedented. We have been here before, but what is different that we forget to think of AIDS when we talk about COVID-19?

There are many differences between the two viruses: routes of transmission, spread, lethality (without treatment HIV is deadly, COVID-19 is not). But there are also key differences of the speed with which science understood the virus, found treatments and vaccines (even today, no effective cure for HIV exists and neither does a vaccine), resources were mobilized, and victims were cared for. These differences are not solely the product of biology or technology.

From its earliest days, HIV was the disease of the gay community, the drug users… of all those belonging to historically marginalized groups of society. It was only when HIV ‘spilled over’ into the ‘respectable’ society (hemophiliac children, straight people, etc.) that it became a ‘crisis’. On the other hand, the early images of COVID-19 the media focused on were middle aged, middle class, white cruise-ship passengers, white nurses and doctors, the elderly, etc. These people were framed as ‘heroic’ and ‘innocent’ victims of a foreign virus that threatened their lives and their families. AIDS victims were not only blamed for their own deaths, but also seen as a threat to the rest of society. COVID-19 has disproportionally affected Black, as well as Latine, and Indigenous communities, and those with unstable housing or employment, and yet it is incorrectly still thought of by many as a ‘great equalizer’ that affects us ‘all.’

When talking about COVID-19, the loud silence about AIDS demonstrates how insidious the erasure of the deaths of gay men and other marginalized individuals can be.

By forgetting, or choosing not to remember, it becomes clear how memory is mobilized. Saying that COVID-19 is “unprecedented” erases the lives, deaths, and grief of millions of people worldwide who live with HIV or have died from it. It also prevents accountability: we will not ask why the government’s crisis response failed, yet again, if we do not know there was just as much of a crisis only 30 years ago—and the government failed then, too.

If anything, AIDS teaches us that memory is political, that remembering and forgetting are political acts with profound consequences for our society, how we define ourselves, and how our histories are constructed.

Jaime García-Iglesias is a Mildred Baxter research fellow at the Centre for Biomedicine, Self and Society at the University of Edinburgh. He holds a PhD in Sociology from the University of Manchester (UK). He has worked extensively on how people make sense of HIV, negotiate risk, and understand intimacy. For more resources on these topics, as well as food pictures, you can follow him on Twitter @JGarciaIglesias.

Resources

Preciado, Paul B. 2020. “The Losers Conspiracy.” Artforum. https://www.artforum.com/slant/the-losers-conspiracy-82586.

Schulman, Sarah. 2012. The Gentrification of the Mind: Witness to a Lost Imagination. Berkeley: University of California Press.