I used to think that NPR was a little over-the-top with their fundraising drives, but at least they never offered to show me a dead body if I donated enough cash.

Some years back, I got a fundraising call from the Goodman Theatre in Chicago. I’m normally pretty good at deflecting these calls, but this guy made it at least halfway through his sales pitch.

“And Mr. Selzer,” he said, “if you donate at the five hundred dollar level, we’ll take you on a thrilling backstage tour…”

“Wait,” I said. “One question. Would I get to see the skull?”

He paused for a second. “Excuse me?” he asked.

“The skull,” I said. “Del Close’s skull. Would I get to see that?”

He paused, then started to laugh, and told me to hold on while he went to ask his supervisor.

In 1999, comedy legend Del Close made a considerable amount of news by leaving his skull to the Goodman Theatre so that next time they do Hamlet, he could play Yorick. I wasn’t sure anyone believed that the skull they had was really, truly, Del’s, but they were known to have a skull somewhere in the theatre, lying in wait.

A minute later, the guy came back to the phone. “All right,” he said. “Now, I know people have been saying the skull isn’t real, but we’re sticking to our story, and I guarantee you that if you donate at the five hundred dollar level, we will make sure you get to see the skull.”

I had to admit that it was a better incentive than, say, a tote bag. And as a ghost tour guide and historian specializing in the more gruesome side of Chicago history, it might have counted as a double tax write-off – both a charitable donation and a business expense. But I just didn’t have that kind of money to spend on seeing skulls.

Still, every night I passed Goodman en route to the site of the Eastland disaster – a site in the river that was also the site where a mysterious submarine, containing the skulls of a man and a dog, was found in 1915. Telling about being offered the chance to see a skull for five hundred bucks was an excellent introduction to the story of them putting the submarine on public display and showing people the skull for just a dime (a nickel if you were under 10 and came in a large group).

Though the guy I spoke to was sticking to the story of the skull belonging to Del, it was actually very well established that it wasn’t really Del’s by then. It was a hoax. Or, if you prefer, one last bit of improv comedy from one of the grand masters of the form.

A FELLOW OF INFINITE JEST

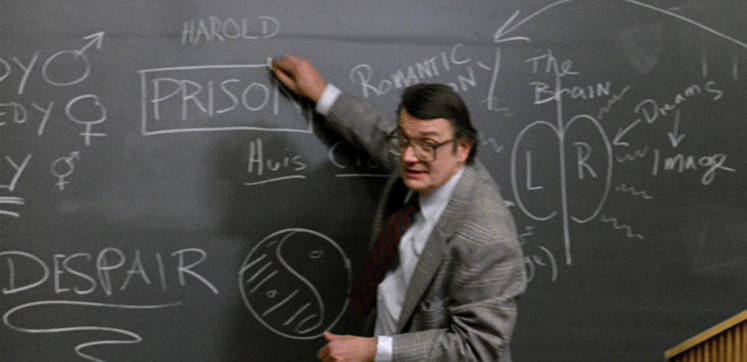

Del Close was one of the early luminaries of the Second City comedy troupe, and students who studied comedy under him make form a veritable who’s who of late 20th century comedy – Bill Murray, John Belushi, Mike Myers, Gilda Radner, Dan Aykroyd, Harold Ramis, Amy Sedaris…. nearly everyone, it seems, especially alums of Saturday Night Live, for which he served as “house metaphysician” in the early 1980s before founding Chicago’s ImprovOlympics. A master of comedy who insisted that improvisation was an art form in and of itself, not just a tool for building scenes, Del was known for his wild storytelling – when he told stories of breaking into a crypt to find a skull to use in a production of Hamlet, even adding details about bits of flesh still being present on the skull he and his buddies boosted, no one dared question him.

Whether that particular story was true or not, he seems to have liked the idea of using a real skull onstage. At some point early in his career, Bob Falls directed him as Polonius in a production of Hamlet, and, according to Bob, it was then that he hit on the idea of donating his skull to a theatre. In the midst of the production, Close told Bob, “When I die, I’m going to donate my skull to you so I can play Yorick.”

Years later, in November, 1997, Close added a clause in his will leaving his own skull to the Goodman Theatre, where Falls was now serving as artistic director. He insisted that he wasn’t dead-set on being Yorick; he was a working actor and would play whatever role they offered him. “He did say that not only would he play Yorick,” says Falls. “He’d be happy to be in a library scene with books resting against him.”

In 1999, Del’s death at Illinois Masonic Hospital became one of the strangest parties of the year. Having elected to have his tube taken out of his throat, even though it would kill him, Del had a few days to meet with old students and tease the nurses who couldn’t find an uncollapsed vein from which to draw blood. “I got there first!” he said, alluding to his years of substance abuse. Bill Murray picked up the tab and hired a saxophone player. At Del’s insistence, pagan priests were brought in to chant. A camera crew from Comedy Central came to watch Del being wheeled in for a birthday party on what he knew would likely be the last full day of his life. “I guess I’d better die now,” he quipped. “Otherwise a lot of people are going to be disappointed.”

Though Chana Halpern, his longtime professional partner, felt that his request for morphine was based mainly on an urge to get high one last time, not just to manage his pain, she had nurses assemble a morphine drip late the next morning. As they put it together, she held his hand, and Del reiterated his wishes for his remains. “Promise me you’ll make the skull thing happen no matter what,” he said.

She promised she would, and the doctors proceeded to give him so much morphine that they were shocked when he was still able to take a phone call (he told the caller “I can’t really talk. I’m in the middle of something right now.”)

Moments later, the morphine – enough to put down a horse, according to the doctor – rendered him unconscious, and he never woke up. He died that evening, and Halpern went about her task of getting the skull.

But how do you get a person’s skull away from their body legally and cleanly? It’s quite illegal in Illinois – and many other states – to remove the head from a human body.

And when Halpern asked the hospital staff if they’d do her a favor and cut off Del’s head, they only laughed. That isn’t the kind of thing they do as hospitals. Still, they suggested that she call the Illinois Society of Pathologists and see if they could arrange it; they probably separated heads from bodies in the name of science all the time.

Halpern gave them a call, and made them an excellent offer. From what she told the New Yorker in 2006, when she came clean on the story, she told the pathologists, “I will give you Del’s body, and it’s a great body, because you can study the effects of smoking, alcohol, cocaine and heroin on the brain. All I need is the skull.” The Society considered the offer, at least for a moment, but had to pass. If word got around that they’d been involved in such a stunt, they could lose funding. Whether it was even legal was beside the point.

Two days later, when the hospital began to insist that the body be removed from the morgue, Halpern had run out of options and had the body cremated, head and all. But she was still determined to keep Del getting acting credits from beyond the grave, and, to that end, she and her sister went out to the Anatomical Chart Company, a medical supply shop in suburban Skokie, where they selected a “manly, manly” skull from the shelves.

That it could actually pass for Del’s skull seemed incredible, but everyone played along. When the Goodman was presented with the skull in an elaborate ceremony, the didn’t say anything about the rusty screws holding it together, or the fact that it had the visible markings of having served as a “teaching skull” in the past. They didn’t even mention the teeth, of which the skull had several (Del wore dentures). Halpern and her sister had tried to get rid of the teeth, but had left a few in the back. “It turns out that pulling teeth is like pulling teeth,” she told the New Yorker. “Plus, who’s going to look back there?”

Even the man at the cremation society had helped play along, in the grand fashion of improv comedy that Del had championed in life. When the press called to ask if the body had arrived headless for cremation, he lied and told them that it had. Chana kept up the story on her end until 2006, when she told the New Yorker the truth.

A ROOM WITH A VIEW

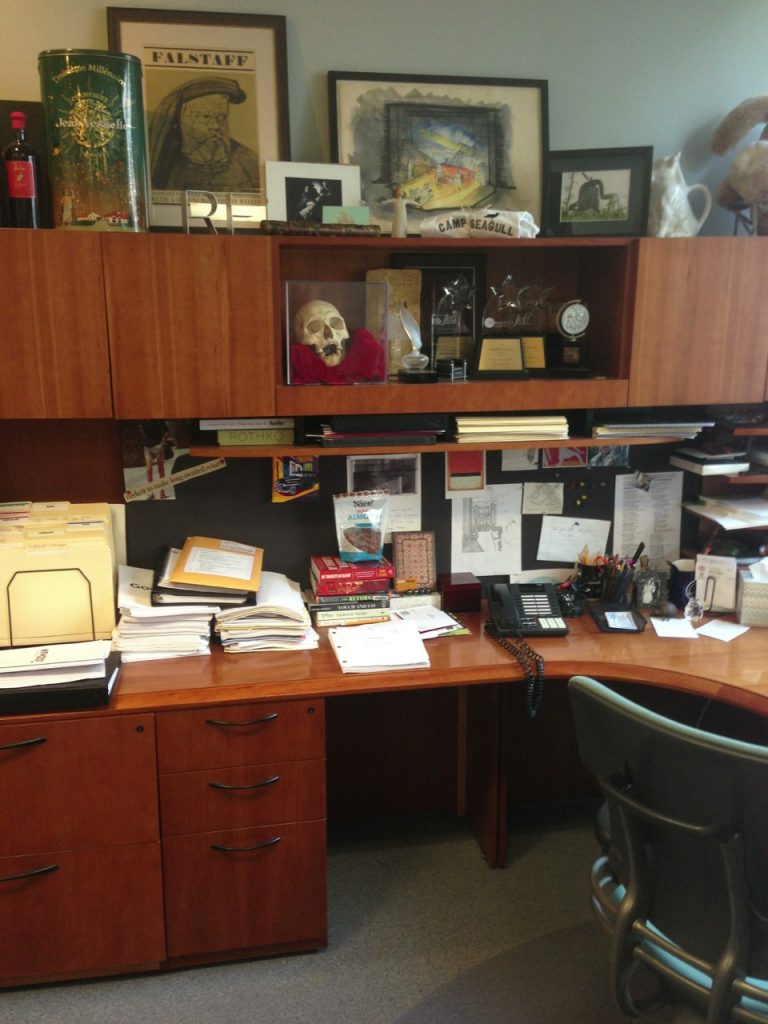

A startup for which I’m doing some work was offered a tour of the theatre last week, and I arrived hoping for nothing besides seeing the skull itself. I was a bit crushed when the tour guide told me it was locked in Robert Falls’s office, and that we wouldn’t be able to see it that day. However, as we toured through the basement, we happened to bump into Falls, who graciously offered to introduce us to Del.

He met us there, in his fourth floor office. The office window looks out on an alley that The Chicago Tribune called “The Alley of Death and Mutilation” after a terrible fire in 1903 in an adjacent theatre, and on a parking garage that stands on the site of a hotel where both Abraham Lincoln and John Wilkes Booth stayed at various times. The skull sits in on a red cushion in a lucite case on the shelves, gleaming white. If having someone’s head in his office weirded him out at all, Falls didn’t let on.

He was quick to admit to us that it wasn’t Del’s original skull, and noted that rumors that it wasn’t his had circulated years before Halpern came clean to the New Yorker. Such rumors created a minor war in the improv comedy world. “Some people were really upset,” he told us, “and some were like, ‘So what?’ Which is actually how I feel. He really, truly wanted to do it, and he couldn’t, so the fact that (Halpern) did this was a sort of a theatrical gesture that I think he would have appreciated. It sort of became more symbolic and conceptual.”

Various articles about Close state that the skull has been in a production or two, but Falls told us that they haven’t found a play for him just yet. But one day they will. And you can bet that the role of the skull will be credited to Del Close.

After all, nearly everyone I spoke to used the same line to describe Del’s relationship to the skull in question: “It’s his now!”

—- Adam Selzer is the author of more than a dozen published books, ranging from young adult novels to adult nonfiction, including a new Ghosts of Chicago book coming from Llewellyn in September. He followed up The Smart Aleck’s Guide to American History (Random House, 2009) with The Smart Aleck’s Guide to Grave Robbing, an ebook which is available now. He maintains a blog about the stranger side of Chicago history.